At the turn of the twentieth century, the countries of Europe and their neighboring empires were entering into a period of intense ethnic awareness. Nations were on the brink of a revolutionary upheaval that would redefine their borders, both geographically and psychologically, paving the way for two World Wars and the ‘age of nationalism.’

For Eastern nations, like Armenia, situated on the cusp of East and West, the same search for identity, the answer to the question What is Armenia?, also had a lot at stake.

Ethnomusicologist Sylvia Alajaji, author of Music and the Armenian Diaspora: Searching for Home in Exile writes that, by the turn of the century, “two ‘Armenias’ were in existence.” Having experienced a formal “carving up” a century earlier between Russian, Persian and Ottoman Empires, Armenia was less a unified nation of like-minded people than it was an ethnic population, scattered across competing empires.

It was divided not only geographically, between East and West, but also by class – between the rural, agrarian peasants who occupied the expansive countrysides, and the intellectual elite in the cities.

Up to that point, the traditions and particularities of Armenia’s large peasant population had been for the most part disregarded by the upper classes. Many urbanites had considered peasant life base and degenerate, but the villages, isolated and untouched by the effects of globalization and modernity, offered a unique opportunity to search for the authentic ‘national spirit’ when the need finally arose. Folk music in particular, the simple songs passed down orally in villages, became a fetishized object of this new movement.

The late nineteenth century saw it become increasingly vogue for musicians to look to the rural countrysides for inspiration. Composers like Jean Sibelius in Finland, Edvard Grieg in Norway and Antonín Dvořák in present-day Czech Republic, gained notoriety for incorporating indigenous musical idioms into their Western-style compositions. Most famously, Hungarian composer Béla Bartók ventured out into the field to collect peasant songs, what he considered the pure sounds of Hungary, and later came to be regarded as a national icon for doing so.

But what does the pursuit of a national identity look like for the Armenians, a people struggling to choose between East or West? And how did music reconcile (or intensify) that schism?

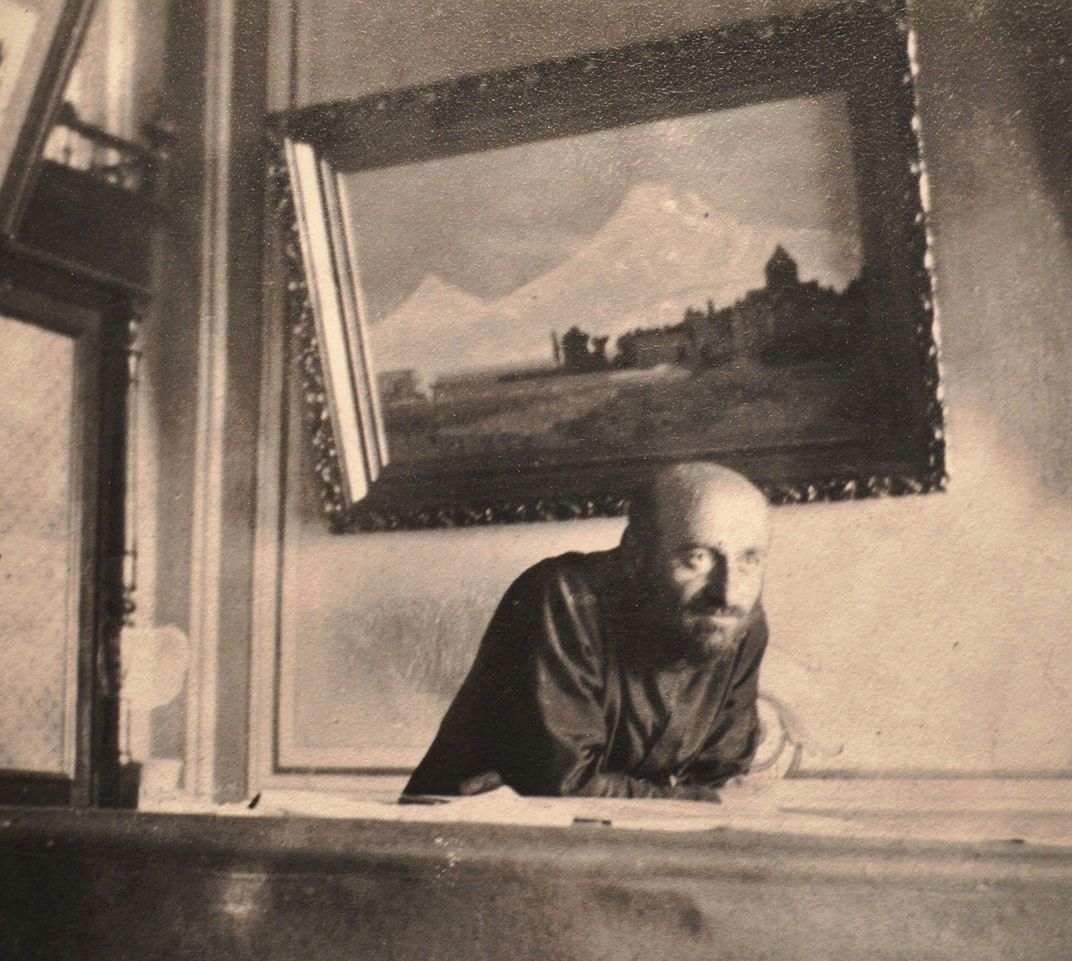

Komitas Vardapet, an Armenian priest and musicologist from Constantinople who traveled across Anatolia collecting and analyzing the music of rural communities, was in many ways similar to Bartók. He received his musical education in Berlin and used his Western training to create a national tradition. He spoke a number of European languages, including French and German, and his primary goal was to promote Armenian music in the West.

Though not a prolific composer, his nearly three thousand transcriptions of folk songs (only around 1,200 are in circulation today) are responsible for developing Armenia’s national style of music. From the vibrant harmonies of beloved Soviet classical composer Aram Khachaturian to the genre-defying tinkerings of jazz-fusion pianist Tigran Hamasyan, the songs he collected continue to form the basis of modern Armenian repertoire to this day.

But if Komitas represented Armenian music in the West… who was the face of Armenian music in the East?

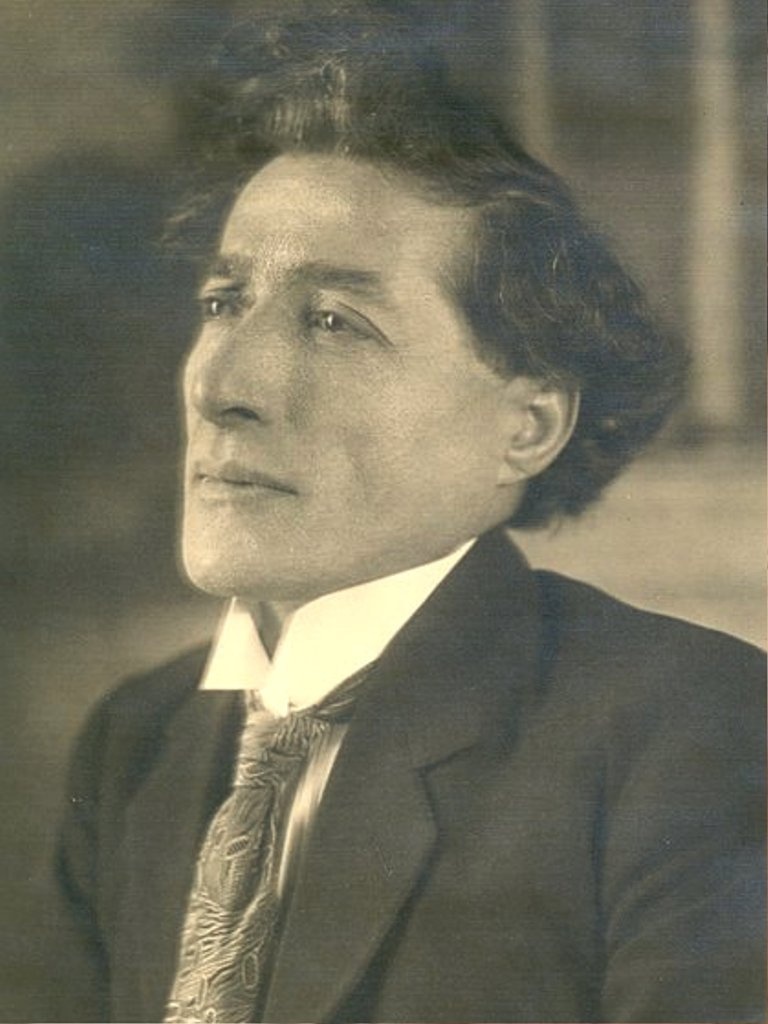

Grikor Suni was a composer and musicologist born in the Russian empire (modern day Nagorno-Karabagh), descendant of a long line of Armenian troubadours. His formal musical education took place in the East, where he studied composition at the St. Petersburg Conservatory of Music under famous Russian composer Rimsky-Korsakov. Suni never completed his degree, but like Komitas, he was relentless in his efforts to promote Armenian music to foreign audiences.

During his time studying Armenia’s liturgical music at Etchmiadzin Cathedral, Suni studied under Komitas and later wrote in his autobiography that he was inspired by his teacher’s openness to folk music. He would go on to spend four months each year devoted to traveling the Armenian countrysides, collecting nearly five hundred songs along the way.

Unlike Komitas, however, Suni was also an outspoken political figure. From a young age, he was affected by the growing socialist movement in Tsarist Russia and later matured into a fervent spokesperson for the Bolshevik movement. This juxtaposition of interests was evident throughout his life. His efforts to document the music of peasants were often accompanied by collections of militaristic fight songs with names like ‘Voices of Blood’ and included lyrics like “Rise up laborers with muscular forearms. Strike the anvil with your hammer. Crumble the old and build the new. Death to this dark system of capitalism, and long live Socialism.”

Due to the political nature of his work, Suni was continually under the threat of arrest and, despite being an Armenian nationalist himself, he was frequently persecuted by – none other than – competing Armenian nationalist groups, divided in their idea of what a modern Armenian nation would and should look like.

He fled to the United States in 1925 and lived out his remaining days in exile, but his music, now dispossessed from its country of origin, suffered a tragic fate. Armena Mardirossian-Suny, Suni’s granddaughter-in-law who led a project dedicated to preserving and publishing his music and writings, wrote, “His commitment to political activism resulted in his music being repressed wherever his politics were out of favor.” Suni’s work fell into obscurity for several generations, and it wasn’t until Soviet musicologist Robert Atayan discovered his music in the mid-eighties, well after “Kruschev’s Thaw” (the period of time after Stalin’s death that allowed for a looser cultural policy) that interest in his work, and its implications for the development of Armenia’s national music, was pursued with great intention.

Suni had been deeply influenced by Rimsky-Korsakov’s interest in developing a nationalist style of classical music, and he sought to pioneer one for Armenia by, like Komitas, gentrifying the songs of peasants. Whereas Komitas did so by preserving stylistic elements, like vocal trills and irregular meters, Suni was known to go a step further, incorporating underlying symbolism in his arrangements.

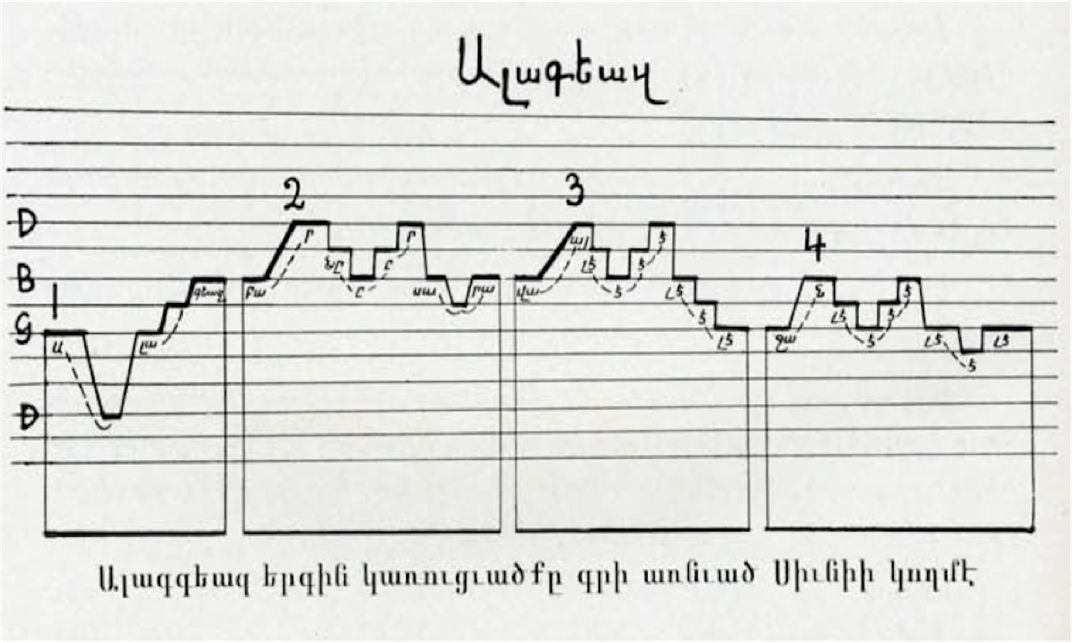

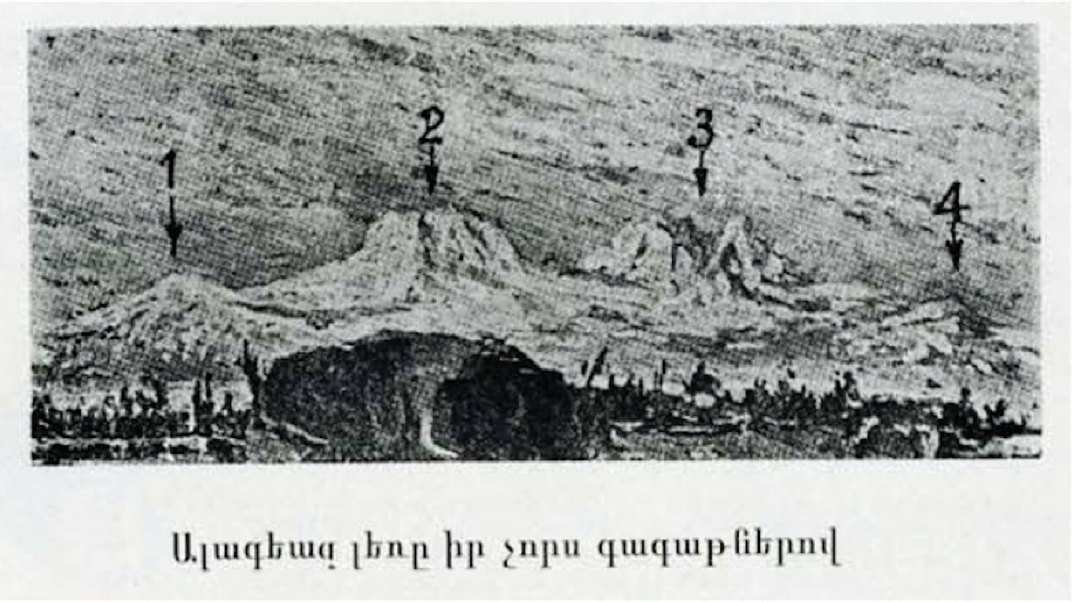

In his setting of the folk song, Alagyaz, for example, Suni quite literally drew a relationship between the melody and the mountain range after which the song is named (the range that is today called Mount Aragats). In a text published four years after Suni’s death, one of his students revealed Suni’s notes on the melody, in which Suni makes an explicit analogy between the peaks of the mountain and the melodic contour. The result was a score that visually traced the mountaintops in the paper notation.

For Armenians, being from the topographically diverse Caucasus region, mountains have historically held enormous meaning, particularly in the villages, where they engendered a shared sense of place. Mountains are a constant theme in folk culture and appear in many songs, like Sareri Hovin Mernim (‘For the Mountain Breeze I’d Die’) or Saren Kooga Dziavor (‘A Horseman is Coming from the Mountain’), but by literally building the geographical formations of the region into the musical score, Suni took this symbolism to new heights.

The irony, however, is that despite the efforts nationalist composers went to in order to demonstrate their national styles, the reality is that what you end up hearing bears very little resemblance to the music of rural peasants. In fact, Bartók himself is quoted to have said that “The only true notations [of folk songs] are the recordings themselves.”

Today, any audio recordings of Armenian villagers that may have been made at that time are now lost, but the comprehensive work of Komitas can be found at the Komitas Museum-Institute in Yerevan, which houses a number of collections of his folk song transcriptions and original compositions.

As for Suni, few resources exist today celebrating his efforts. His politics presented obstacles wherever he went. In the East, he was a threat to the Russian Tsar. In the West, his ties with Russia made him dangerous to Ottoman forces. Even amongst his own Armenian compatriots, his music was not welcomed, for his Bolshevik tendencies did not align with their ideas of a free and independent Armenia. (Though later in his life, he was enraged to discover these nationalists had appropriated a number of his revolutionary fight songs for their cause, keeping the melodies but changing the socialist lyrics.)

And finally, when Suni’s dreams of a Soviet Socialist Armenia finally realized in 1922, he was all but deserted by the one group that should have embraced him, because by the time of his death in 1939, it was official Soviet policy under Stalin to omit from nationalist narratives any cultural or political figures who had fled to the West, even out of self-preservation.

His was work which, even now, cannot easily find a home, because the question remains: To which Armenia does it belong? It was the ability of music to navigate this complex and delicate territory, that gave composers such revolutionary power at the turn of the century, for they became the unlikely mediators between East and West, between rich and poor, between villages and cities, and between melodies and mountainsides.