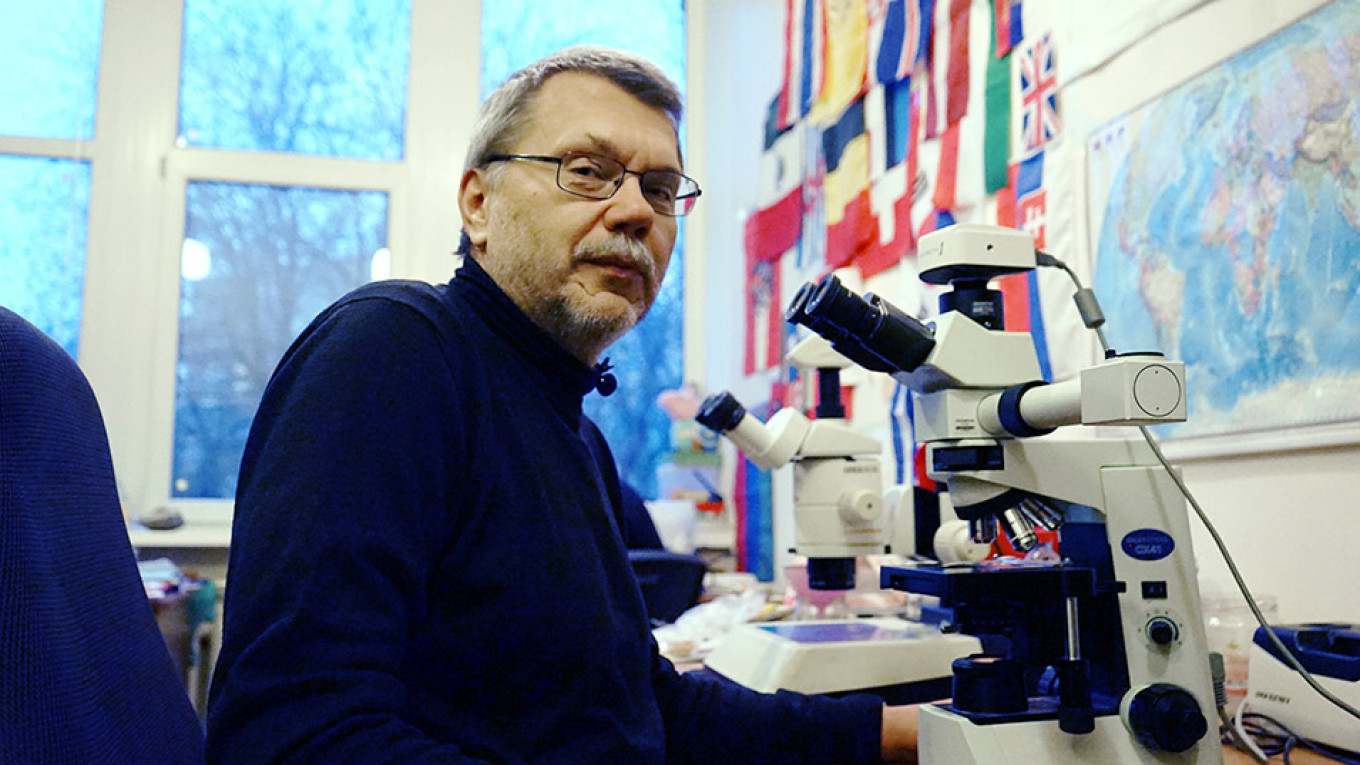

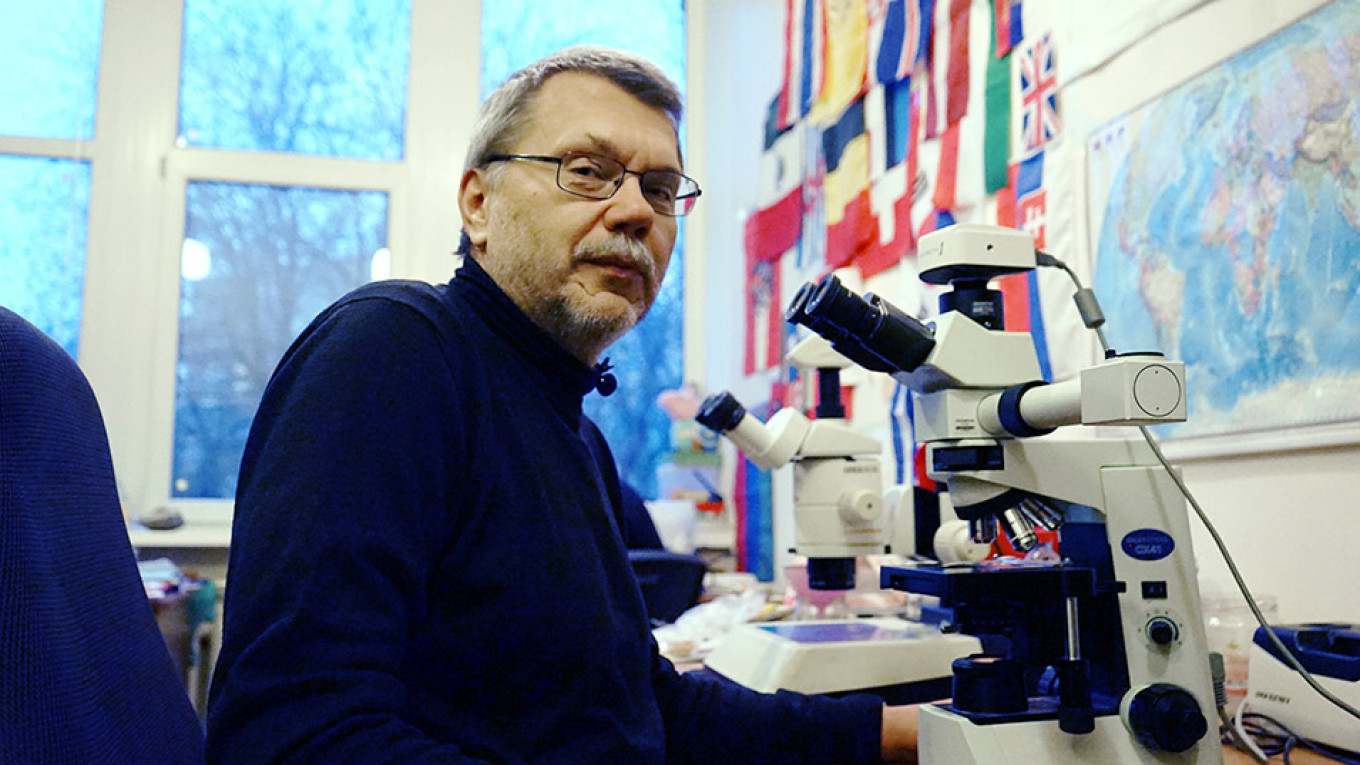

Professor Alexei Kotov greets his colleagues as he navigates the poorly-lit corridors of the Institute of Ecology and Evolution in the south of Moscow, where he has been a leading researcher and member of the Russian Academy of Sciences since Soviet times.

“This whole street was built during the Stalinist period, and I don’t think anyone has renovated our building since then. We try to spend our whole budget on research,” he says.

Kotov, 54, was one of 11,000 scientists from 153 countries who signed an open letter Tuesday declaring a global climate emergency. The warning of “untold suffering” as a consequence of climate change made headlines around the world and called for urgent changes. These included curbing population growth, leaving fossil fuels in the ground, halting forest destruction and drastically cutting meat consumption.

But while Russia is the world’s fourth-largest emitter of greenhouse gases, just four of the letter’s signatories were Russian.

Russian authorities have forecast that climate change will bring epidemics, drought and mass hunger if left unchecked. This summer, the country experienced a series of large-scale floods and forest fires scientists believe to be directly linked to climate change.

The general population remains unconvinced.

Research has shown that less than half of Russians — 43% — believe climate change poses a major threat. In Germany, that number is 72% while 90% of Greeks believe climate change danger is imminent.

Kotov “didn’t think twice” when he received the letter from his foreign peers in an email.

“It is absolutely clear this is a crisis. Fires, floods, our permafrost is melting … It is a nightmare for Russia.”

Kotov said he is most worried about Russia’s Arctic regions, which the Environment Ministry has said are warming at a faster rate than the rest of the world.

Just this week, Russia’s meteorological service Roshydromet said the Arctic archipelagos of Franz Josef Land and Severnaya Zemlya had experienced the warmest October on record, with average temperatures on the islands 8 degrees Celsius higher than normal.

“The ecosystem there is so vulnerable,” Kotov said.

He added that while he doesn’t know if the letter will make any difference, he hopes it will at least bring some awareness to the cause in Russia.

“Many of our politicians, the only time they see nature is when they’re lying on the beach in the Maldives or Miami. For them, the decision-makers, climate change feels very fictional and distant.”

It’s just as important to make ordinary Russians aware of what is happening around them, he added.

“You see those people across the road?” he said, pointing to an office building, “They don’t really think all this is going to affect them. They care about what is on TV tonight.”

While Russia has recently seen a wave of ecology-inspired protests across the country, Kotov said the problem is that people are still struggling to make the connection between their direct environmental concerns and global climate change.

Climate strike movements

Russians have been largely absent from global climate strike movements, including Extinction Rebellion and FridaysForFuture, protests that have prompted millions of people to take to the streets.

“I am not asking for a movement like the one started by the girl in Europe,” he said, referring to 16-year-old Swedish activist Greta Thunberg. “But it would be good if we could see the bigger picture.”

In September, Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev said Russia would implement the 2015 Paris Agreement to fight climate change. With the ratification, Russia also drafted a set of laws that aimed at reducing its global footprint.

However, it soon became clear that the government had watered down the new package of climate change legislation to a huge degree after push-back from the country’s leading businesses.

“I don’t think we should be surprised that many of the laws that were proposed won’t happen,” Kotov said. “The problem is that many at the top see climate change as a business opportunity.”

He specified melting ice caps that are opening up the Arctic Northern Sea Route, which experts believe could be beneficial for Russian trade.

Despite his skepticism about the business community, Kotov was quick to defend Russia’s science community when asked why so few Russians had signed the letter.

“To be honest, I think many more of our scientists would have signed the letter if they had known about it. Maybe it’s a reflection of the political realities,” he said, adding that both Russia and the West are to blame for the poor cooperation between climate experts.

A precedent for the setting of barriers between Russian and international scientists was set last August, when a senior member of the Russian Academy of Sciences complained that the authorities had recommended scientists avoid communicating with their foreign colleagues.

Kotov’s words were echoed by Russia’s veteran climate scientist Sergei Zimov, who told The Moscow Times he would “definitely” have signed the letter if he had been made aware of it.

Kotov is pessimistic about the future, saying he fears the worldwide interest the open letter has sparked might have come too late.

“My 8-year-old daughter will never know what a real Russian winter is,” he said.