We’re living in a golden age of presidential comedy on television. Presidential candidate Donald Trump hostedSaturday Night Live in November 2015, igniting a firestorm of controversy about the benefit the appearance might give his campaign. Hillary Clinton had appeared on the sketch comedy program the previous month, as Bernie Sanders would in February 2016. Impersonations of Trump, Barack Obama, Clinton and others have been the mainstay of late-night comedy for years, not to mention politically-charged monologues from such television luminaries as Stephen Colbert, John Oliver and Samantha Bee.

It may seem normal now, but it hasn’t always been this way. Following the tumult of the Great Depression and World War II, the august institution of the presidency was seen as too dignified to be subjected to anything more than the most mild and bipartisan ribbing, especially on that low-brow medium known as television. That all changed in 1968 when Richard Nixon appeared on Rowan & Martin’sLaugh-In.

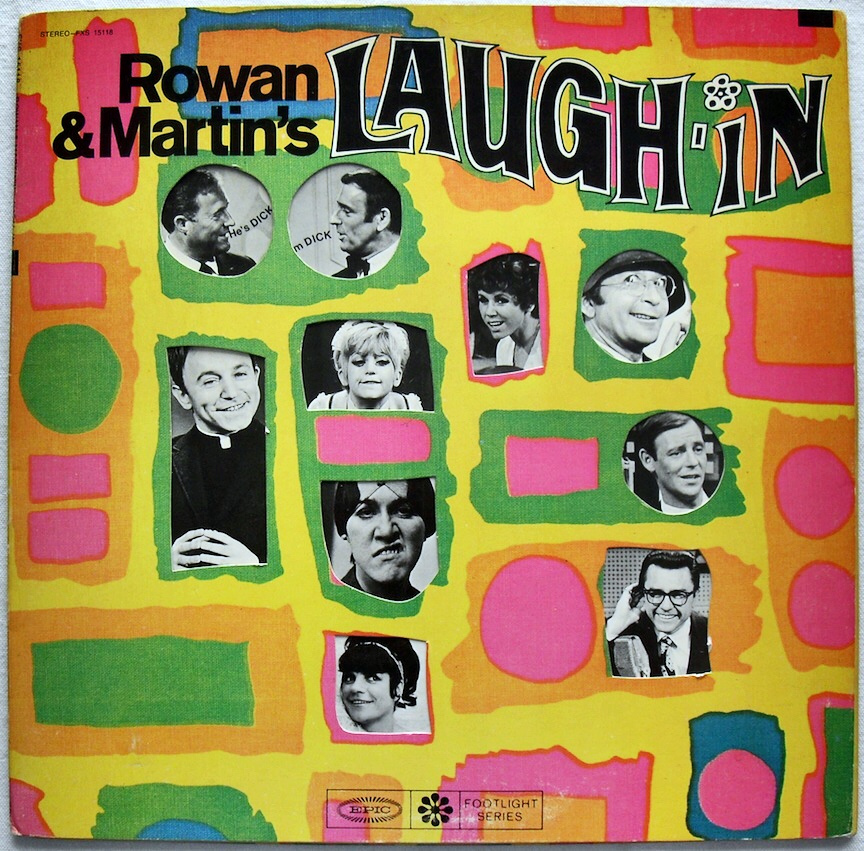

Fifty years ago this month, Laugh-In premiered on NBC, and it quickly became a phenomenon.

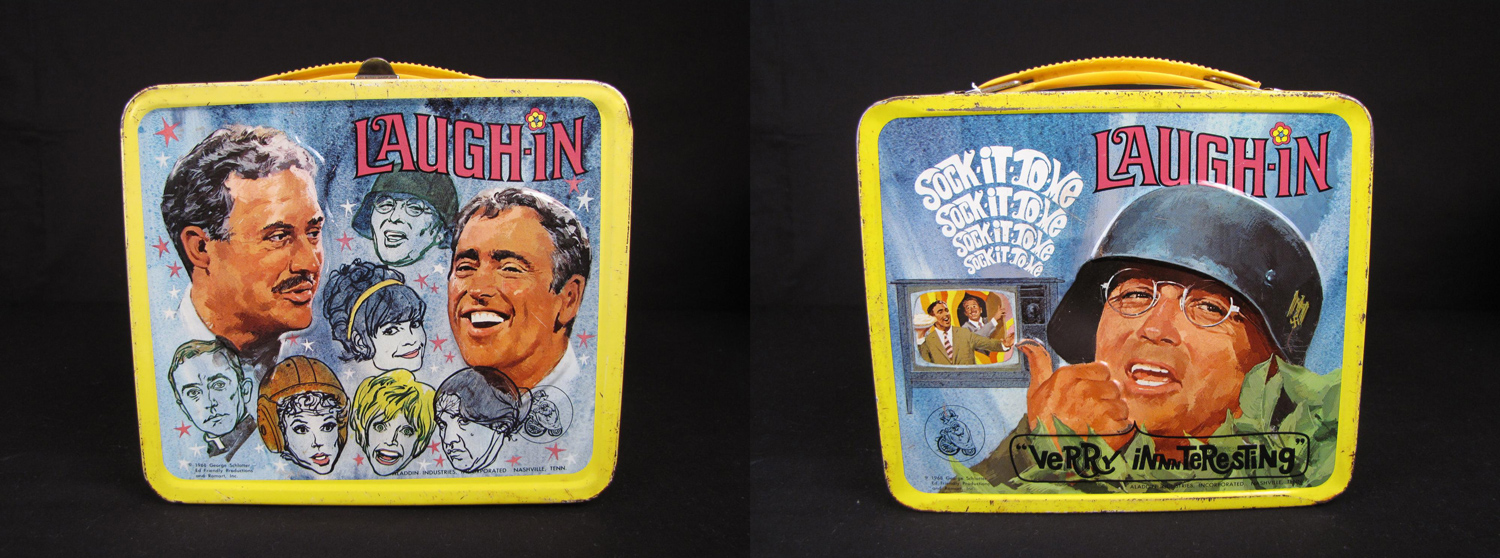

Combining fast-paced one-liners, absurd sketches, non-sequiturs, musical performances and celebrity appearances, the show paved the way for television sketch comedies, including Saturday Night Live (producer Lorne Michaels was a Laugh-In writer). It also launched the careers of numerous actors, especially women, including Goldie Hawn, Lily Tomlin and Ruth Buzzi. It introduced catch phrases like “sock it to me,” “verrrry interesting,” and “look that up in your Funk & Wagnalls.”

Perhaps the most long-lasting and influential moment in Laugh-In’s incredibly successful five-year run, however, was that cameo appearance by presidential candidate Richard M. Nixon in 1968.

It wasn’t very funny by modern standards, but Nixon’s stilted delivery of the show’s signature catchphrase “sock it to me” was part of a revolutionary effort to reach out to younger voters, taken against the advice of Nixon’s campaign managers.

The show’s title, Laugh-In, referenced the sit-ins and be-ins of the Civil Rights and hippie movements. Laugh-In’s creators Dan Rowan and Dick Martin updated the traditional vaudeville show to give it a modern flare. Like its CBS peer The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, Laugh-In spoke to its politically aware, and socially conscious audience with rapid-fire one-liners.

The memorable set design, the mainstay of the show, was a summer of love-styled joke wall painted with brightly-colored psychedelic designs and flowers. Actors swung open doors to deliver their quips and one-liners, most of them barely able to control their laughs. But it was the faux news segments and the comedy sketches involving bumbling judges and police officers that with a wink and a nod challenged traditional forms of authority.

So why did the straight-laced, establishment candidate Nixon appear on this wild, countercultural program? Nixon had famously flubbed his television personality test in the groundbreaking 1960 Presidential debate, the first ever broadcast on network television. Compared to the young, telegenic John F. Kennedy, Nixon, who was recovering from illness and exhausted from a weekend spent campaigning, looked pallid and sweaty. Eight years later, Nixon, who never again participated in a televised debate, was eager to project a better image on the small screen.

Laugh-In writer Paul Keyes, a fervent Nixon supporter and media adviser, convinced the candidate to make the brief cameo while campaigning in Los Angeles. At first, Keyes suggested Nixon could make a reference to the show’s catchphrase “you bet your sweet bippy,” but the candidate wasn’t having any of it.

According to television historian Hal Erickson, Nixon told his advisers that he didn’t know what ‘bippy’ meant, and didn’t want to find out. They settled on “sock it to me,” but producer George Schlatter recalled that it took six takes for Nixon to make it through the phrase without sounding angry or offended. Schlatter remembered running out of the studio with the Nixon cameo footage, fearful that the candidate would change his mind or that his campaign team would try to stop him, but television history had been made.

Nixon’s cameo appeared on the season premiere of Laugh-In’s 1968-1969 season, two months before Election Day. The candidate also wisely aired a campaign ad during the episode, spending top dollar for a spot on what was the number one rated program that season.

For his part, Nixon received the standard $210 appearance fee for his work, which went straight into his campaign coffers. His short stint as a Laugh-In guest certainly didn’t swing the election for Nixon, but its boost to his relatability certainly didn’t hurt in a tumultuous election shaped by assassinations, street violence and protest over the war in Vietnam. Fellow presidential candidates Hubert Humphrey and George Wallace were also offered the opportunity to appear on the show, but both declined.

Laugh-In reached its zenith of popularity and cultural influence that season, before losing star Goldie Hawn to Hollywood and feeling less fresh as competitors like The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour and All in the Family further pushed the boundaries of political humor. The show slipped from its number one ranking in its 1968-1969 season to 13, then 22, then 35 by its final season in 1973. The show had ushered in a new era of contemporary and political humor, but then couldn’t keep pace with the rapidly changing face of television.

The Smothers Brothers never scored a guest appearance by a presidential candidate, but their more direct and pointed political satire seemed to better match the mood of the young television audience by 1969.

On their Comedy Hour, Tom and Dick Smothers had evolved from gregarious and milquetoast folk singers to important comedic commentators on topics ranging from the Vietnam War and the draft to race issues and civil rights. Challenging the entertainment industry’s blacklist for individuals suspected of communist ties, they invited Pete Seeger back to television to sing “Waist Deep in The Big Muddy,” a thinly-veiled critique of President Johnson’s Vietnam policy.

Their merciless mocking of the political system with Pat Paulsen’s satirical presidential campaign was matched only by its jabs at organized religion with the notorious sermons of comic David Steinberg. But perhaps most brazen of all occurred in the third season when producers tried to air a segment with Harry Belafonte performing his protest song “Don’t Stop the Carnival” against a backdrop of footage of police beatings at the 1968 Democratic Presidential Convention, but the bit was cut before the broadcast.

Battling the CBS censors and landing themselves on Nixon’s list of enemies, the Smothers Brothers didn’t just reference current events; they encouraged their audience to take a stand. The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour may have surpassed Laugh-In in contemporary relevance, but it didn’t last as long on air. Amidst controversy, CBS canceled the show during its 1969 season.

Today, it’s hard to imagine a time in which comedy and presidential politics were separate spheres, but 1968 marked a turning point in television and political history. Laugh-In writer Chris Bearde recalled receiving a call from President-Elect Nixon in the writer’s room two weeks after the election thanking the show’s cast and crew for helping him get elected. Though George Schlatter took heat from friends for aiding Nixon’s campaign, in recent interviews he has recognized the importance of that moment in television history. “Now you can’t have an election without the candidates going on every show in sight, but at that point it was revolutionary.”