Turkey and Russia have opened a joint military facility in Azerbaijan to help monitor the ceasefire with Armenia, a stark indicator of the shifting geopolitics in the region.

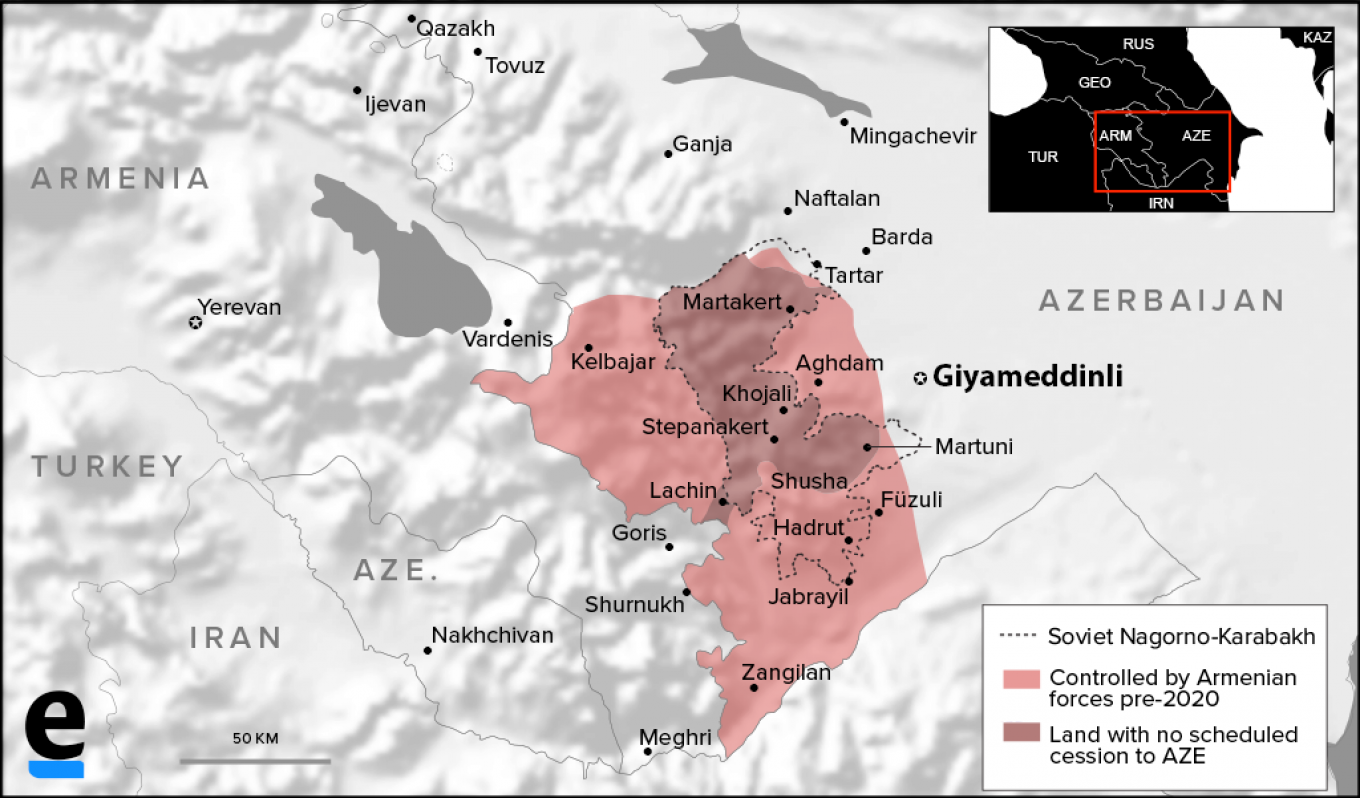

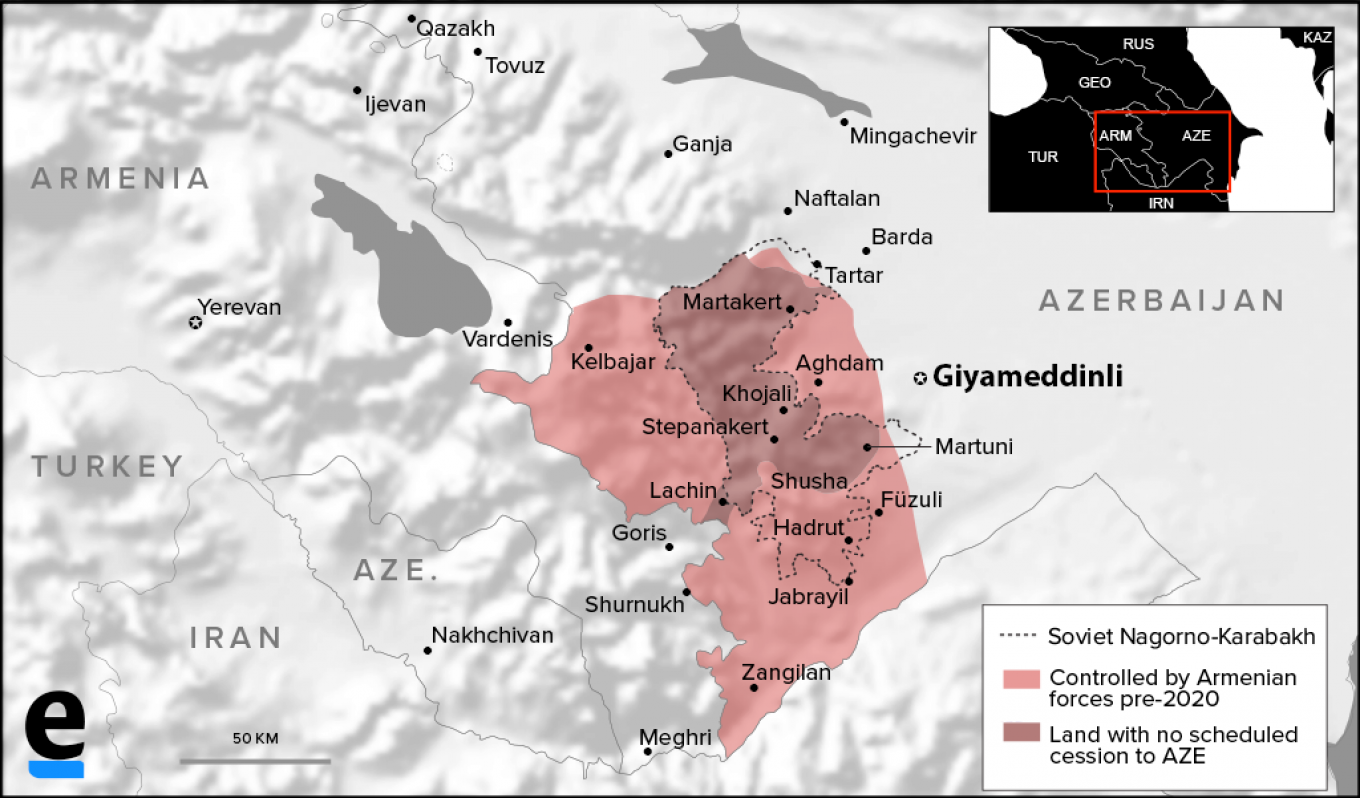

The center formally opened on Jan. 30, near the village of Giyameddinli in the Aghdam region. Staffed by an equal number of Russian and Turkish troops — 60 on each side — it is novel in a number of ways.

It represents the first formal Turkish military presence in the Caucasus in more than a century, and the first Russian military presence on Azerbaijani-controlled territory since Baku effectively kicked the Russians out of a radar facility in Gabala eight years ago. It also is a rare case of direct military cooperation between the two historical foes who have lately become custodians of a shaky security condominium in their shared neighborhood.

Official information about the center’s precise mission is scarce. But according to a dispatch from the center in the Russian Izvestiya newspaper, the primary mission appears to be as a base for surveillance drones to monitor the new ceasefire lines between Armenian and Azerbaijani forces. The Russian troops use Orlan-10 and Forpost drones; the Turks use Bayraktars. The intelligence is used to support the 2,000-strong Russian peacekeeping contingent that operates on the territory in Nagorno-Karabakh that Armenian forces still control.

The two contingents appear to work in parallel, and there is no single commander: each side has its own general in command. Even the formal name of the center avoids favoring one side over the other. In Turkish, it is called the “Turkish—Russian Joint Center,” while in Russian the proper names are the other way around: “Joint Russian—Turkish Center.”

“Information from the drone reaches the headquarters of the Russian contingent, where it is processed and transmitted to the monitoring center,” Izvestiya’s source, one Colonel Zavalkin, reported.

He didn’t report on how the Turkish drone operations worked, and there don’t appear to have been any comparable dispatches from Turkish reporters. “There, service members of the two countries jointly serve round-the-clock.”

“The monitoring center decides how to react when the ceasefire is violated,” Colonel Zavalkin continued. “This is where the authority of the center is the broadest. It can pass the information on to the command of the Russian peacekeepers or by direct line to the defense structures of Armenia and Azerbaijan.”

The operational role of the center appears secondary, however — Russian drones were already monitoring the ceasefire, and the addition of Turkish forces is unlikely to cardinally improve that capability. The significance appears to be more about the emerging regional politics around the Caucasus.

The center was born out of the Nov. 10 ceasefire statement that ended the 44-day war between Armenia and Azerbaijan, which resulted in Azerbaijan winning back most of the land it had lost to Armenians in the first war between the two sides in the 1990s.

The original ceasefire statement — signed by Russia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan — did not stipulate the creation of this center, or for that matter any role for Turkey at all. In that agreement, the Russian peacekeeping force has the sole responsibility for monitoring compliance. But following the signing of that deal, Russia and Turkey negotiated bilaterally to set up this center, signing an agreement on Dec. 1. The structure itself was constructed by Azerbaijan.

The diplomacy that led to the agreement was opaque but it’s obvious that of all the interested parties, Azerbaijan and Turkey were by far the most desirous of the center, with Russia not nearly as enthusiastic and Armenia even less so.

Azerbaijan got substantial support, both militarily and politically, from Turkey during the war and the two countries’ relations are now as warm as they have ever been. Baku especially has sought to deepen its ties with Ankara in the aftermath of the war and sees Turkey as a means of balancing out a newly reinvigorated but potentially pro-Armenia Russian influence in the region.

There appear to have been three main drivers for the center’s creation, said Hasan Selim Özertem, an Ankara-based analyst of Turkey and the Caucasus.

“First, after supporting Azerbaijan during the war, Turkey seems to be interested in keeping a foothold in the region as a show of power projection,” Özertem told Eurasianet.

“Second, Azerbaijan wants to keep Turkey in the equation to balance Russia,” Özertem said.

And finally, the joint operation helps Russia and Turkey sideline outside actors: “So, Turkey gains leverage in international politics, particularly against the West, as a factor in the region that cannot be ignored, while also establishing a link with Moscow,” he said.

Azerbaijan’s favoring of Turkey was made clear in the twin press releases put out by the Azerbaijani defense ministry describing parallel talks at the center’s opening on Jan. 30 with the military leadership of Russia and Turkey. The two releases repeated much of the same language word-for-word, but one praised “the eternity and inviolability of the Azerbaijani-Turkish brotherhood” — a level of effusion entirely missing from the description of Russian-Azerbaijani ties.

And Turkish Deputy Defense Minister Yunus Emre Karosmanoğlu reportedly “congratulated the Azerbaijani people on the victory in the Patriotic War, wished the mercy of Allah Almighty to the souls of all servicemen and civilians who died as Shehid [martyrs] and healing to the wounded.” His Russian counterpart, Colonel General Alexander Fomin, did not offer any similar sentiment.

Russian officials, meanwhile, have tended to downplay the significance of the new center. “This is a stabilizing factor but I wouldn’t call it an element of a long-term policy or create any conspiracy theories here,” Dmitriy Medvedev, the deputy chairman of the national security council, told journalists on Feb. 1. “We just need to recognize the reality in our region, that today we need to discuss this issue with our partners in Turkey.”

That new order was also noticed, ruefully, among Armenians. “What does this Russian-Turkish monitoring group mean? One simple thing: Russia is continuing its policy of bypassing the Minsk Group,” said political analyst Stepan Grigoryan, in an interview with Armenian news site 1in.am, referring to the diplomatic body led by Russia, France, and the United States which used to broker negotiations between Armenia and Azerbaijan but which has been sidelined since last year’s war.

Grigoryan was asked why Armenia allowed the creation of the center. “No one asked us,” he said. “It is clear that our opinion was ignored.”