“They brought me to a dimly lit room filled with a heavy stench,” Denis, 34, said of his arrest in southern Russia by Federal Security Service (FSB) officers. “There was a big table, eerie concrete walls, floor and ceiling, and — this was imprinted in my memory — a portrait of Putin. It looked like a torture chamber. They forced me to sit on a chair, put a plastic bag on my head again and started beating me.”

Denis was arrested last year on apparent suspicion of involvement in an anti-Kremlin paramilitary group fighting alongside the Ukrainian army. He is now sharing his story for the first time.

For safety reasons, his surname and some details about his story have been withheld.

For years, Denis had been a part of the fan culture surrounding his hometown Moscow’s FC Spartak football team. When Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, he said the fan community split in two, with those who supported the invasion on one side and those who opposed it on the other. Denis fell into the second camp.

“I had more right-leaning views before, but of course, when the war started, I supported Ukraine. I have people I know there, even friends, Ukrainians I constantly kept in contact with,” he told The Moscow Times.

Today, he said he believes that he caught the FSB’s interest because a pro-war fan told the authorities that Denis was planning to enlist in one of the Russian paramilitary groups fighting against the Russian army in Ukraine.

On Jan. 12, 2023, Denis was crossing the border with Georgia for a “vacation” when he was stopped by border guards and asked to unlock his phone.

After he refused, the guards undressed him and discovered a tattoo of an Iron Cross — a German military emblem often used by the far right — on his shoulder. The Iron Cross is considered by Russian authorities to be a display of “extremist” or “Nazi” symbols, a crime in Russia.

The border guards’ examination swiftly turned into an interrogation. Denis was accused of “wanting to kill Russians” and asked how many of his friends had gone to fight for Ukraine.

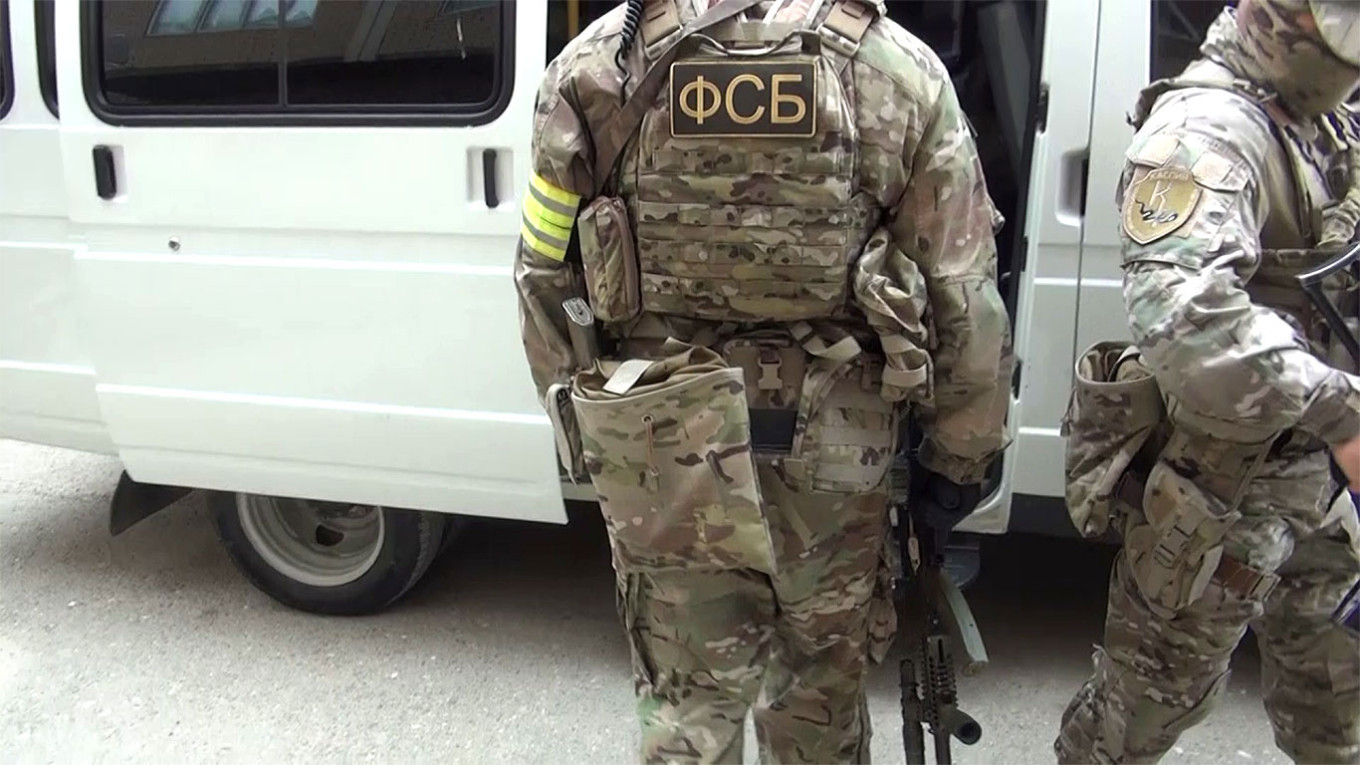

The experience recounted by Denis reflects a wider trend in which the FSB targets people believed to be involved with the volunteer paramilitary groups fighting for Ukraine, which have launched several cross-border incursions since the start of the war.

“A lot of effort is put into identifying not just those who are cooperating with these organizations, but also anyone remotely inclined to do so,” Yevgeny Smirnov, a lawyer and civil rights activist who focuses on persecution by the special services, told The Moscow Times.

In late March, the FSB said it had arrested seven people in Moscow. The suspects were alleged supporters of the Russian Volunteer Corps, one of these militias.

“The FSB and their associates try to probe people to find out their attitude toward the Russian Volunteer Corps and the Freedom of Russia Legion,” Smirnov said. “If a person turns out to be at least slightly sympathetic, the enforcers provoke them to formulate the ‘right’ phrase: a phrase fit for prosecuting that person as a terrorist.”

Interrogation

After refusing to unlock his phone a second time, Denis said the border guards started slapping his face and spitting at him. He threw his phone against the floor in frustration, breaking the device. Soon after, the guards handed Denis to FSB agents, who put a plastic bag over his head and locked him in a minivan.

“‘We’ve already stamped your passport. It means that you have already crossed the Georgian border. You are f***ed. Everyone will think you fell from a mountain, and nobody will ever find you’ — that’s how they were threatening me,” Denis recalled. “I told them my mother was a lawyer and that she would find me.”

He said he believes the building he was eventually brought into was the regional FSB headquarters in Vladikavkaz, the capital of the North Caucasus republic of North Ossetia.

“They brought me to a dimly lit room filled with a heavy stench. There was a big table, eerie concrete walls, floor and ceiling, and — this was imprinted in my memory — a portrait of Putin. It looked like a torture chamber. They forced me to sit on a chair, put a plastic bag on my head again and started beating me. They demanded that I unlock my phone.”

Denis said he was able to endure the beating because he was physically in shape.

“They kept abusing me, but at one point they took the bag off so that I wouldn’t suffocate,” he said.

“But then they moved to the most unpleasant part of the ‘interrogation’ — the electricity. My hands were cuffed to the chair behind my back. They greased both of my hands with something and started electrocuting me. I don’t know if they were using a live wire, but it felt like one. They shocked my neck once too, but they were mostly passing the current through my hands.”

The FSB officers repeatedly accused Denis of being a Nazi. Fed up, he told them they were Nazis themselves, as they were the ones abducting a person and torturing him with electricity.

“What, you think the SBU [Security Service of Ukraine] is any better?” he recalled one of the officers saying in response.

When Denis could no longer endure the torture and humiliation, he kicked the chair over while still cuffed to it, and started rolling on the floor and moaning. His interrogators removed his handcuffs and sat on him.

“Then I curled up so that they couldn’t unclench my hands or hurt me in any way. I remember one of them laughing and saying ‘Look, he’s acting like he’s exercising.’ I don’t remember how long it lasted. … I lost track of time, it was like a bad dream.”

After a while, Denis finally managed to break away and run to the next room over, a kitchen. The officers cornered him against a wall.

One FSB officer who wore a Columbia Sportswear hat and appeared to be the commander ordered the others to stop.

“If only you’d use all that energy of yours for the right cause,” Denis recalled the man saying.

“I won’t tell you what I thought at that moment,” Denis said.

“They cuffed me again, put a bag on my head and put me into a car. They kept saying ‘We don’t give a f*** about you, it’s just a matter of time before we hack your phone. You’re just making things worse for yourself’.”

Arrest

Denis was returned to the border checkpoint and asked to sign a document stating he had no legal complaints against the police and had voluntarily agreed not to cross the border. He refused and was transferred to the local police, who brought him back to Vladikavkaz.

The next day, a court charged him with disorderly conduct for swearing at the border crossing and sentenced him to 15 days of arrest.

During the last hour of his sentence, Denis was visited by the head of the detention center, who ordered his staff to report Denis for allegedly making a mess in his cell. He was then moved to a holding cell and left there overnight.

“They had left me to spend the night locked with a hobo-looking alcoholic. It was winter, so I was wearing a parka and jeans,” he said.

In the morning, security officers brought him into a room where he was met by eight individuals who identified themselves as employees of Russia’s Center for Combating Extremism.

“It turned out that my cellmate reported me to the police and claimed I was showing him my Iron Cross tattoo — in other words, ‘displaying a symbol of an extremist nature.’ The cross is tattooed on my bicep, you can’t even see it from under a shirt. Maybe they gave him a bottle of vodka to report that.”

Denis was then brought to the court again and charged with the administrative offenses of dirtying his cell and displaying an “extremist symbol.” His mother, a practicing lawyer, came to Vladikavkaz but was not allowed to represent her son. He was arrested for another 11 days.

Once he was released from custody, Denis and his mother returned to Moscow, where he was detained almost immediately after getting off the plane.

“At the baggage claim, I saw policemen talking on their radios and looking at me. I realized what was going on — and in a moment they walked up to me and told me I was to be arrested, as I was on the BOLO [law enforcement bulletin].”

Denis was brought to a building across from the airport. His mother’s claim that she was his legal representative was again ignored.

“I was brought into an interrogation room and seated at the table. Then two individuals wearing face masks came in. The first one started asking me about football fans, about Ukraine, all of these questions again. Then he pointed at the second thug and said ‘Look, he just came back from the front, you are f***ed’.”

Denis was again asked how many of his friends had gone to fight for Ukraine and pressed to explain why he broke his phone. After he did not answer, the interrogators made Denis sign an agreement saying he had voluntarily cooperated with the FSB.

He was sat in front of a camera and forced to promise to remove his tattoo and to say he supported Russia’s “special military operation” in Ukraine.

“They must have thought they would get dirt on me like this. They told me, ‘We’ll keep it for ourselves, so that your friends would beat the s*** out of you, just in case.’ They also said that I must report anyone willing to join the Russian Volunteer Corps or who is already a part of the organization.”

Departure

After leaving the building, Denis said he decided he could no longer live in fear. Within a month, he had left Russia. He asked that the details of his departure not be published due to safety reasons.

According to human rights activist Smirnov, despite torture being prohibited under Russian law, law enforcement services encourage the practice among its officers.

Last month, the key suspects in the Crocus City Hall massacre appeared in court with clear signs of abuse after unverified footage appeared to show them being tortured during their interrogation.

“Before the war … 90% of those charged with terrorism were tortured — and it didn’t even matter if they were proven guilty. Now, since the beginning of the war, the number of criminal offenses where torture of suspects with impunity is allowed has increased,” Smirnov said.

Experts interviewed by the Financial Times said the Russian special services’ top priority is suppressing the pro-democratic opposition and persecuting those who support Ukraine — and that they prioritize these efforts over preventing actual terrorist threats.

As a result, the gruesome interrogation practices, including torture, once reserved for terrorism suspects have increasingly been directed at political activists.

“It’s like there is a solid wall: even if there is physical proof of torture, like bruises or marks from electrocution and beating, getting justice is virtually impossible,” Smirnov said. “It appears to be a coordinated policy, implying that anyone supervising compliance with the law is supposed to turn a blind eye.”