Bordering Russia’s southern regions, the Caspian Sea has long been plagued by industrial pollution, falling water levels and more.

This is the only place on earth that is home to the Caspian seal, a species whose numbers have drastically shrunk in recent decades due to environmental degradation.

If no additional measures are taken, scientists estimate that the species could go extinct within two decades.

In May, Russia proposed recognizing the Caspian seal as “under threat of extinction” in an effort to ramp up preservation efforts. While experts welcome this progress, they warn that it is moving far too slowly.

“Granting the Caspian seal a new [protected] status is commendable, but it is followed by yet more talks about counts and continued observations rather than direct actions to protect the species,” Arseny Philippov, president of the Nativus International Association for Biodiversity Conservation, told The Moscow Times.

Listed as an endangered species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature since 2008, the Caspian seal is classified as “rare” in Russia’s Red Book of rare and endangered species.

The Natural Resources Ministry seeks to upgrade its status to “under the threat of extinction” — just one step away from “extinct.”

“We see that the number of this rare species is concretely heading toward extinction,” Irina Makanova, head of the ministry’s protected areas department, said during a State Duma meeting in May.

According to Makanova’s data, the Caspian seal population has dropped by nearly 80% since the early 20th century.

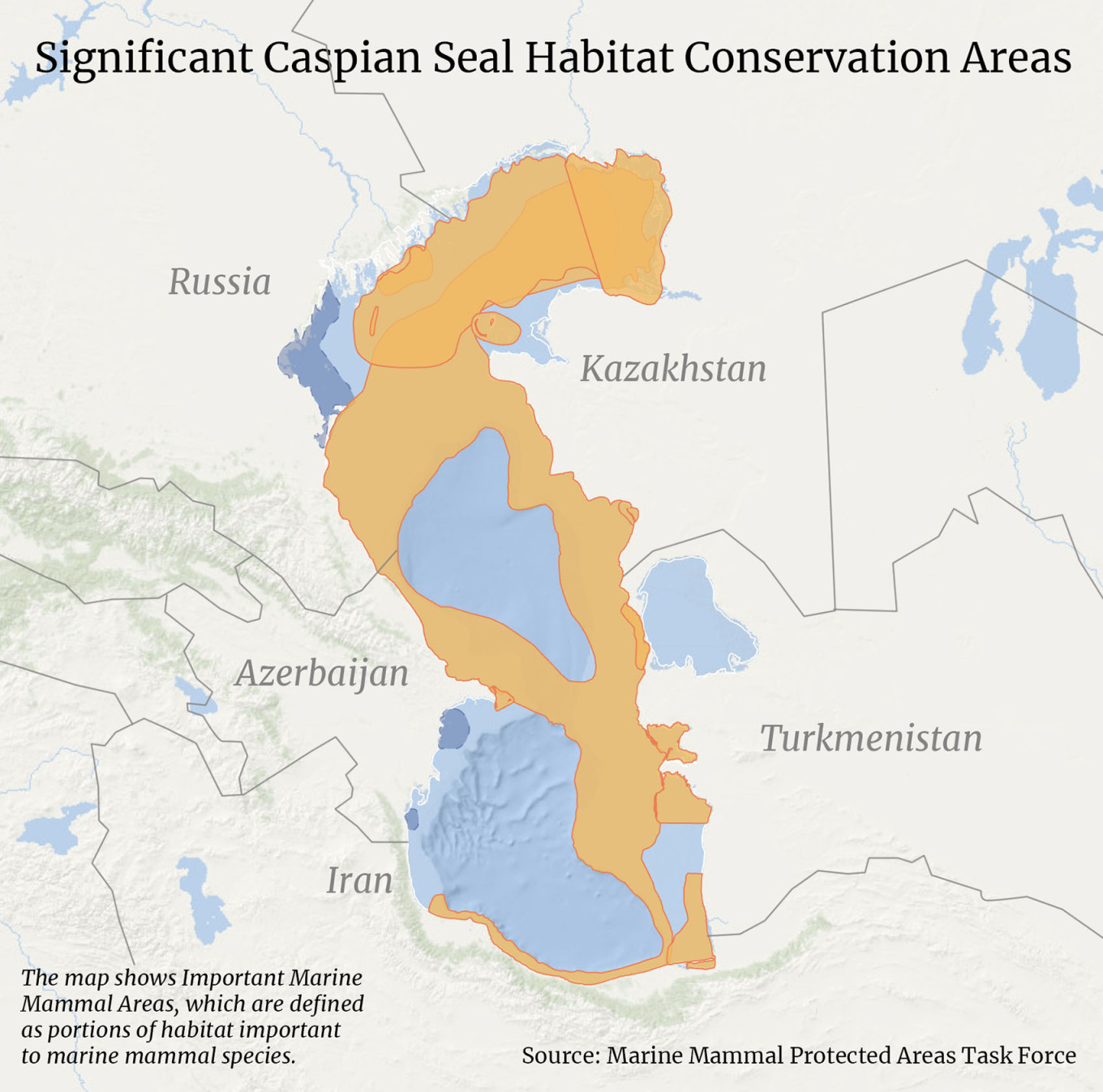

Environmentalists have previously voiced frustration over a lack of robust conservation measures such as establishing a network of protected areas. Tightening the Caspian seal’s conservation status would allow officials to create a dedicated conservation plan.

‘Cumulative toxicosis’

Historically, hunting for fur and blubber has been a key factor in the Caspian seal’s population decline, an international expert in marine mammal conservation told The Moscow Times.

This expert spoke on condition of anonymity due to the risks of speaking with a media outlet labeled “undesirable” in Russia.

Hunting of the mammal is currently illegal as the species is red-listed in all five Caspian countries, with Kazakhstan outlawing the practice in 2006 and Russia in 2019.

However, other threats remain.

“While there is no longer officially organized commercial hunting, there is very high bycatch of seals in illegal fishing gear set for sturgeon poaching, amounting to many thousands of animals each year,” the international marine mammal conservation expert said.

“This is likely to be the biggest current threat to the population,” they added.

Russia’s Red Book also points to poaching — which culls several thousand seals every year — as the species’ primary human-induced threat. Other stressors include shipping near the animals’ breeding grounds, industrial pollution and the depletion of food sources due to fishery.

The expert also pointed to habitat loss, diseases and ecosystem change due to invasive species and overfishing — threats whose contribution to the seals’ population decline are less understood.

The Caspian Sea is polluted with a wide range of toxic substances including petroleum products, pesticides, mercury, lead, arsenic and phenol.

As a result of these combined negative factors, scientists have diagnosed the Caspian seal with what they call “cumulative toxicosis.”

Meanwhile, climate change is exacerbating the species’ decline in several ways.

One significant effect is the reduction or early melting of winter ice cover, a crucial breeding ground for Caspian seals.

Climate change is also expected to increase evaporation over the Caspian Sea, leading to a sea level decline of about eight to 14 meters by the year 2100, with adverse impacts on the ecosystem.

“Even the lower value [the least sea level decline] would mean the North Caspian — about one-third of the total current area of the Caspian Sea — will disappear,” the international expert said.

“This means the area where the winter ice sheet currently forms, which is the breeding habitat for Caspian seals, will be gone.”

Requiem for a seal?

Despite the alarming decline of Caspian seals and the looming threat of climate change, experts offer some reasons for optimism.

One encouraging sign is the species’ potential for recovery. A notable example is the Northern Elephant seal, which bounced back from just a few dozen individuals in the late 19th century to a population of several hundred thousand today. In Europe, gray and harbor seal populations have also rebounded following bans on hunting and reductions in pollution.

Caspian seals may even have the ability to adapt to climate change. Having lived in the Caspian Sea for at least 1 million years, they have already survived several past climate shifts.

The question remains whether they can withstand the rapid pace of climate change — the speed of warming more than ten times that at the end of an ice age — amid all the other simultaneous human pressures.

Philippov and the international expert both stressed the urgency of designating the species’ key habitats as protected areas to ensure their survival.

“This will buy an important breathing space in adapting to longer-term challenges from climate change and the other ecosystem scale threats,” the international expert said.

“Exactly the creation of a nature reserve can provide a chance to save the species. This is precisely what we, together with scientists and activists from Dagestan, demand in our petition,” Philippov said.

The anonymous expert also highlighted the need to develop alternative livelihoods for fishing communities in regions like Dagestan so that people will not have to resort to illegal fishing that causes seal bycatch.

International organizations can bolster national conservation efforts, while individuals can contribute by adopting sustainable fishing practices and refraining from consuming threatened species like sturgeon.

“My personal view is that we absolutely have the opportunity to conserve Caspian seals,” the international expert said.

“But the decision to do that is in the hands of people now. They have to actively decide to take action and do it, or stand by and watch as they slip away.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia’s Prosecutor General’s Office has designated The Moscow Times as an “undesirable” organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a “foreign agent.”

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work “discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership.” We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It’s quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you’re defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Once

Monthly

Annual

Continue

Not ready to support today?

Remind me later.

×

Remind me next month

Thank you! Your reminder is set.