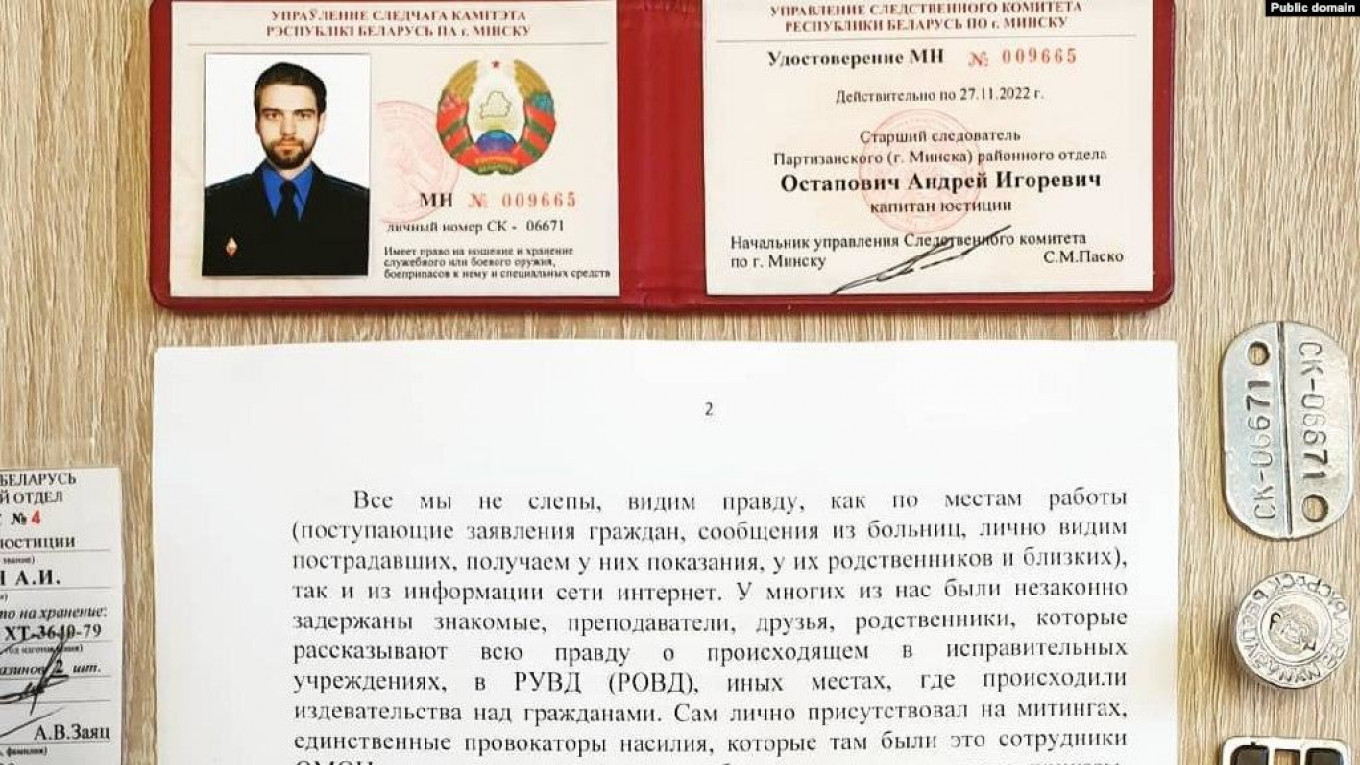

A week after Belarus’ contested presidential elections, senior police investigator Andrei Ostapovich decided he could no longer stay silent.

He had already started to lose faith in President Alexander Lukashenko and even took part in one of the first post-election protest marches. The turning point came on his first weekend shift after the Aug. 9 elections when his superiors asked him to investigate protesters who were detained in Minsk for damaging a police van, charges he believed to be trumped up by the authorities.

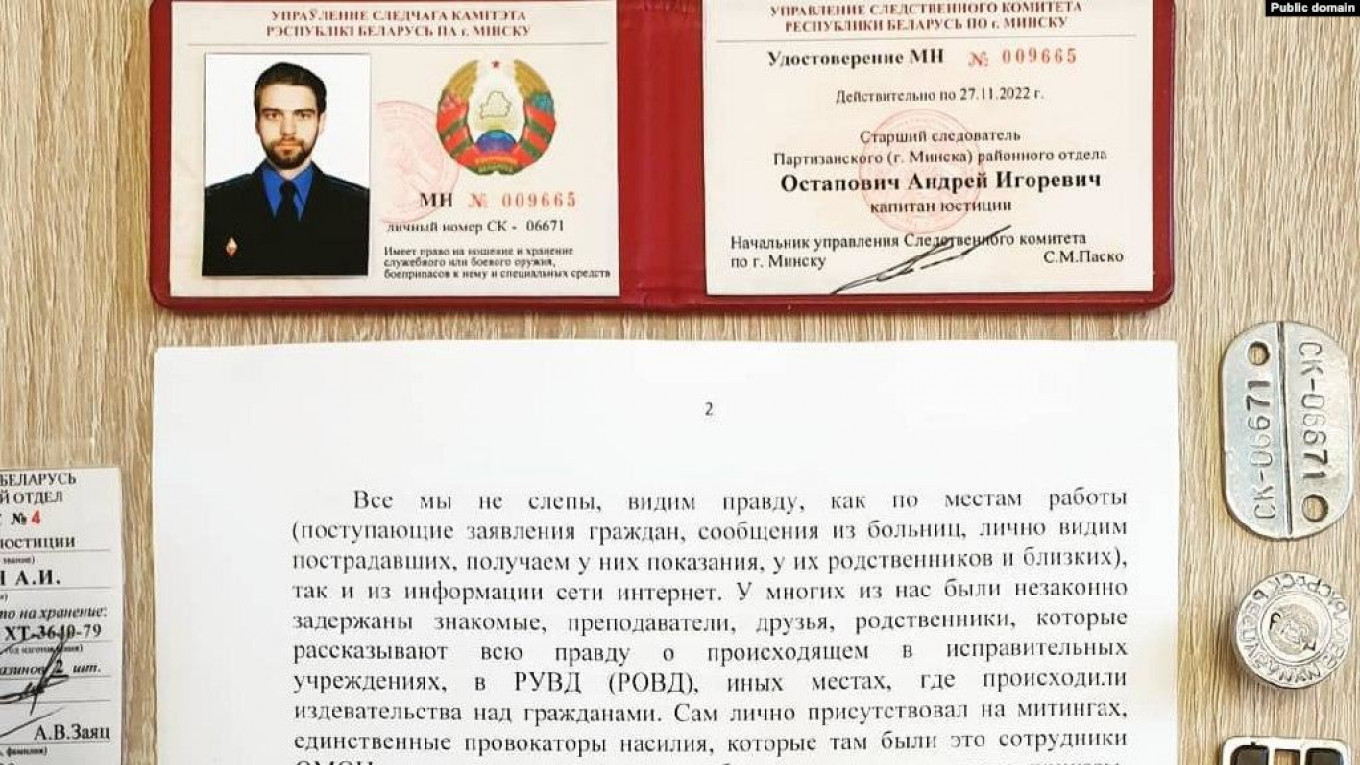

“I saw with my own eyes the lawlessness of the police and the total disregard for the rule of law. I knew I wasn’t going to take part in the crackdown, I had to make a statement,” he told The Moscow Times.

He left a resignation letter on his desk on Aug. 16, called in sick and left for Moscow — soon after, his Instagram post featuring a picture of his resignation letter calling for fellow Belarusians to “kick out the dictator” went viral.

Ostapovich says his life since then has been a rollercoaster ride that has included detention in Russia, hiding from police in a Belarusian forest and eventual escape to Poland.

He is one of the few state workers to have left Belarus since protests over the election broke out. While Lukashenko has faced strikes at state-run factories that for a long time were seen as the core of his political support, he has not yet seen any high-profile desertions from his government and looks set to retain the support of the security apparatus that he has developed during his two and a half decades in power.

Neither the Russian Federal Security Service nor the Belarusian Investigative Committee have responded to requests for comment on Ostapovich’s claims.

Ostapovich understood that his problems were just getting started soon after his arrival in Moscow, when he said he received a message from a “high-placed” friend in Belarus that said the authorities had started looking for him the day after his Instagram post and were aware that he was in Russia.

Realizing he had to get out of the country, he contacted the Latvian authorities who promised him he would get a visa once he made it across the Russian-Latvian border.

Break for the border

He hired a car and drove for nine hours to the Latvian border. Once there, Russian border authorities refused to let him cross due to Covid-19 restrictions and he was advised by the Latvians to go to their closest consulate in Russia’s western city of Pskov.

In Pskov, local police arrested him on what he describes as “made up” public disorder charges.

After a night in a prison cell, officials told him to leave through the emergency exit. Once outside, he said he was met by seven men in ski masks who he believes were members of Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB).

Ostapovich said they blindfolded him, bundled him into a van and handcuffed him to a kettlebell.

“My mind started racing. Are they going to throw me into the river? I knew I was a very good swimmer but a 30 kilogram weight might be the end of me,” he said.

According to human rights organizations, several activists in Belarus went missing when the protests started. While most were eventually accounted for, the director of a military history museum who reportedly refused to sign an electoral protocol stating Lukashenko had won the presidential elections was found dead weeks after the elections, Belarusian media reported.

“You just don’t know what they will do with you. They could have staged my incidental death if they wanted to,” Ostapovich said.

After a few hours in the car, he said he started to hear what sounded like multiple trucks passing by, which made him suspect they were approaching the Belarusian border. His abductors made him take off his blindfold and told him he was in the Vitebsk region of Belarus, on the border with Russia.

They added that he was banned from entering Russia for five years for taking part in a “hostage plot that involved Wagner soldiers.”

Belarus in July arrested 33 Russian mercenaries from the private military contractor Wagner Group for allegedly plotting to destabilize the country ahead of the presidential election. The Belarussian government later said that the mercenaries were lured into a trap that was part of a special operation carried out by the Security Service of Ukraine.

“It was an absolutely absurd allegation, but I decided not to tempt my luck and not question them,” Ostapovich said, adding that he believes the men he identified as FSB left him on the empty road rather than handing him over to Belarusian security services because in the days just after the election Russia was not yet publicly backing Lukashenko.

“You have to remember this was before all the Putin-Lukashenko talks. Russia wasn’t yet openly helping Belarus so they wanted to be more discrete,” he said.

Ostapovich’s Russian lawyer, Vyacheslav Golovin, confirmed details of Ostapovich’s extraordinary story to The Moscow Times and said he believes Russian security forces brought him out of the country.

“Most likely, he was taken to Belarus by Russian security services. I doubt he was getting a lift from Good Samaritans,” Golovin told Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty shortly after Ostapovich was taken across the border.

Five days in a forest

Moments after the Russian van drove off, Ostapovich saw what he believed to be a Belarusian police van speeding down the road toward him, and ran for cover into one of the forests that cover much of Belarus.

He would spend the next five days there, drinking water from creeks and rationing the little food he had with him.

“Luckily, I had brought one of those big bags of Snickers with lots of minibars. All my other stuff was left behind at the hotel in Pskov,” he said.

The first two nights were spent dodging flashlights and hiding from Belarusian police.

As things “calmed down,” Ostapovich said he started walking around 70 kilometers a day.

At some point, disoriented, he said he got stuck in a swamp, leaving him “at an emotional and physical low point.” Another night he said he was chased by a wild boar, making him “tremble to the core.”

On Sept. 3, two weeks after his Instagram post went public, he made it to Poland.

Ostapovich said he was helped by a number of people along the way, but declined to give more details because of “safety concerns” for them.

In Belarus, he is now facing official charges of “illegal actions of a state official.”

“One day I hope to tell the full story,” he said.

Ostapovich believes that, in a small country like Belarus, every defection like his own will weaken the regime.

“Eventually, the dam will burst.”