Amid snow-covered trees in eastern Moscow, a group of clergymen leads a prayer service to honor an upcoming church dedicated to those who died in military conflicts.

A young man, identified as a participant in what the Kremlin calls the “special military operation” in Ukraine, blesses the church, stressing the importance of prayers “for those killed in battle.”

The reporter points to the nearby Mourning Mothers statue devoted to soldiers who fell in the Afghan war.

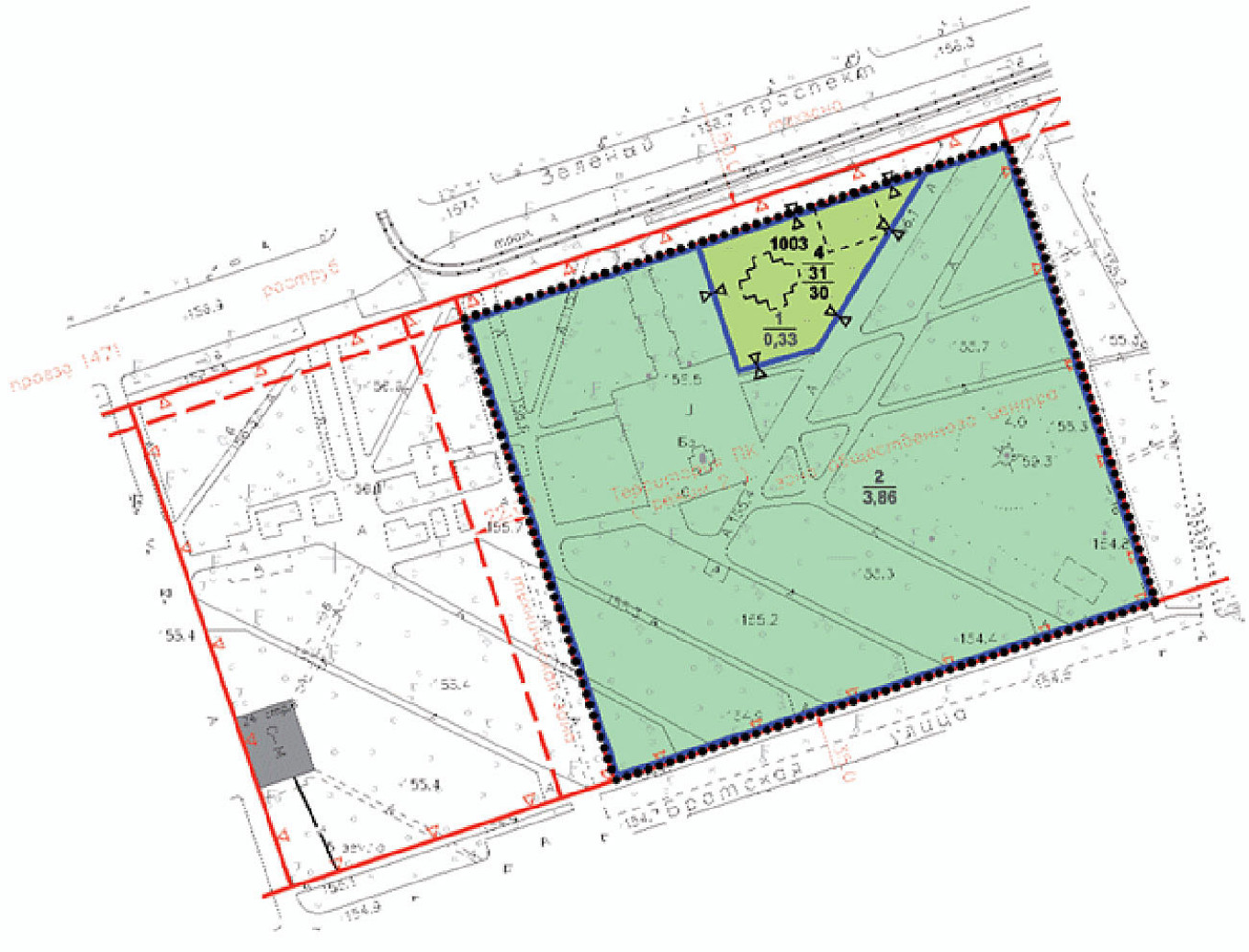

These scenes aired in late November on the state-run Rossia 1 broadcaster took place in the Park on Zelyony Prospekt, a green area in Moscow’s Novogireyevo district.

Absent from the TV feature was the fact that hundreds of locals have been protesting the construction of a church at the expense of their neighborhood’s park for over a decade.

“They believe that we need a church in every apartment! Our country is famous for accepting all religions, sure. But at the same time, people need a space to live,” said Maria, a local woman, standing in front of an excavator that broke ground in the park in November.

“They will build a church from sidewalk to sidewalk, then they need a parking lot, then they promise some school here, then the priest needs somewhere to live. And then that’s it, the end of the park,” she added.

Prayers for heroes

The Park on Zelyony Prospekt has been a hotspot of public discontent since 2012, when the Moscow government allocated part of its grounds for the construction of a church.

Developers attempted to break ground in 2012, 2015 and 2016, but the local community managed to halt the project each time, residents told The Moscow Times.

Grassroots resistance against the development of parks and other green spaces is a common sight across Russia.

The park’s defenders stress that they do not pursue any religious or political aims — only the goal of saving the park from development that violates several laws.

“We are ordinary residents, we have no organization, we just want to preserve proper living conditions for ourselves and our children,” a Novogireyevo resident since 2006 who identified herself as Basya told The Moscow Times.

“We’ve made numerous appeals [to officials], wrote letters and continue to do so,” she added. “Everywhere, the responses state that everything is fine and the church will be built.”

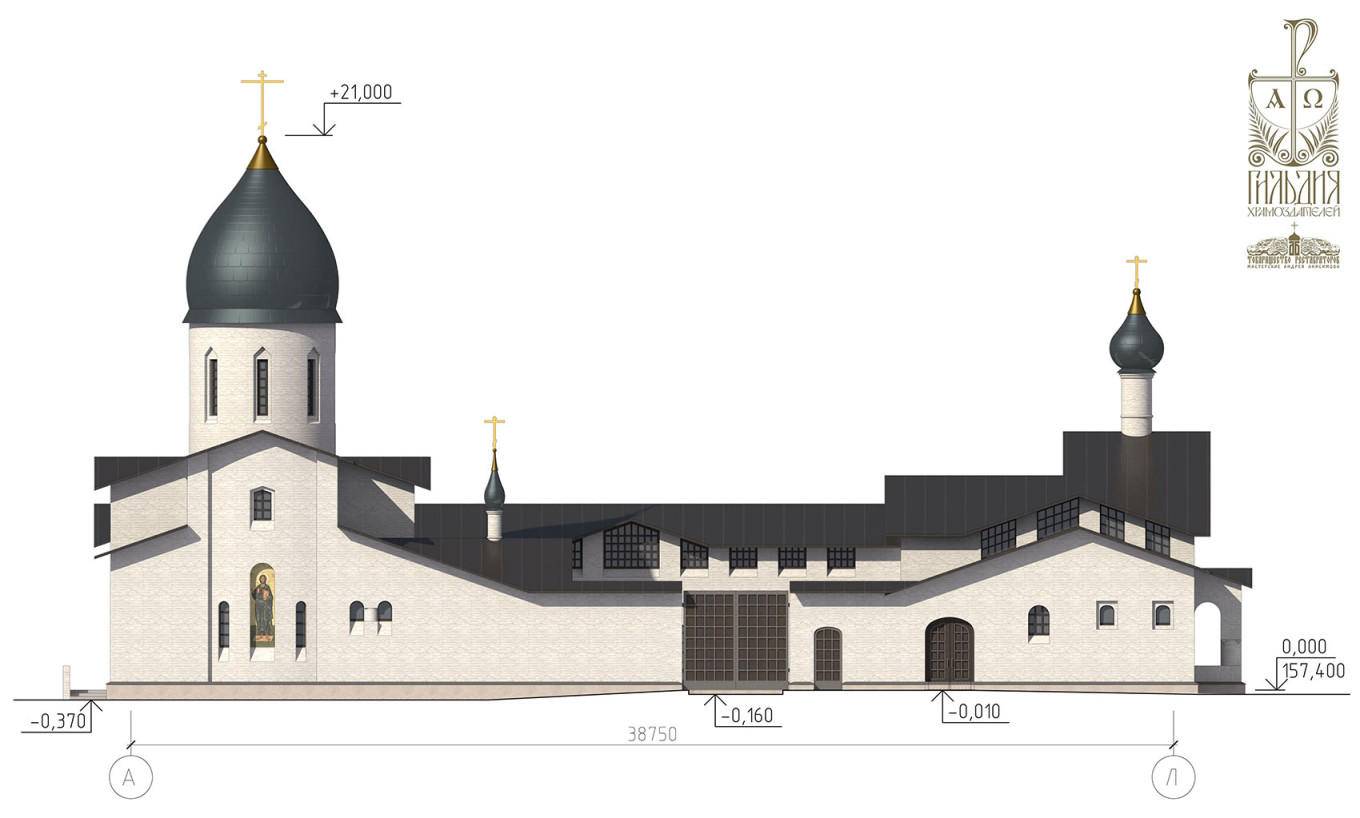

This modest park, measuring just under 400 meters in length and about 200 meters in width, has previously had military connotations.

Locally known as Afgansky Park because of annual gatherings commemorating the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan, the initial plan in 2014 was to dedicate the new church to soldiers who were killed in the Soviet-Afghan war.

However, amid Russia’s war in Ukraine, officials and religious leaders have started to present the project as the primary memorial cathedral for veterans of all military conflicts.

The church is backed by the Moscow government as well as lawmaker Andrei Kartapolov, the head of the State Duma Defense Committee and a vocal supporter of the Kremlin’s military actions in Ukraine.

“The main Church of War Veterans should become a place of bright memory for those who, risking their lives, defended the interests of the Fatherland,” Kartapolov said in November 2022, stressing the importance of remembering “the heroic deeds of the heroes of our Great state.”

While about 1,200 people staged a rally to defend the park in 2019, speaking out against the military veterans’ church has become considerably riskier almost five years later under tightening wartime censorship.

“As of 2024, protecting the park has become significantly more challenging,” Basya said. “People are afraid to openly express their opinions, especially men and government officials because this directly relates to political aspects.”

Another resident who identified himself as Mikhail told The Moscow Times that the park’s legal protections have recently been weakened in favor of developers. The authorities also restrict people’s right to assemble under the guise of anti-Covid measures.

“In addition, opponents of the park in online chats occasionally threaten us with ‘discrediting the army,’ which they try to attach to absolutely any expression,” Mikhail said, referring to the country’s wartime censorship laws.

500 churches

The proposed church in Novogireyevo is just one of hundreds of places of worship planned or already built in Moscow under Program-200, a “walkable distance” Orthodox church expansion plan and one of the pet projects of Russian Orthodox Church head Patriarch Kirill.

Launched in 2011, the program initially aimed for 200 new churches to be built in residential districts, a number that had increased to over 500 by 2021.

Between 2011 and 2023, the total number of Orthodox churches in Moscow reached 246.

“We have the capacity to deliver 15 new churches annually. I hope it will remain the same in the coming years,” said Program-200’s curator, State Duma deputy Vladimir Resin, in late December, adding that the construction benefits the city by creating new areas for recreation and walks.

These ambitious plans in some cases result in conflicts when authorities and developers overlook local residents’ opinions. This was seen with the backlash over Torfyanka Park in 2015-2016 which resulted in a rare victory for the protesters.

Patriarch Kirill took a hard line on opponents of churches’ construction, saying in 2016 that they should be silent and suggesting in 2019 that they were “assisting” dark forces.

Program-200 was necessary because of Moscow’s shortage of churches, Sergei Chapnin, a senior fellow at the Orthodox Christian Studies Center at Fordham University and former executive editor of a leading publication of the Russian Orthodox Church, told The Moscow Times.

Churches in the Russian capital are largely concentrated in the city center, he said, and are notably scarce in residential districts designed during the Soviet era.

However, it is only possible to build several hundred new churches through infill development, which has led to “serious conflicts” with locals.

“In some places, the Church and municipal authorities retreated and changed the construction site after protests, while in others, conflicts were put on hold to wait for ‘better times’,” Chapnin said.

The Church and Patriarch Kirill are rapidly losing credibility among the public because they do not engage in open dialogue during conflict situations, he said.

“These are clear signs that the Church is not with the people but with the authorities. And ordinary people will respond accordingly, they will say, ‘This is not the Church that is with us, this is the Church that is together with the state against us’,” Chapnin noted.

Even when faced with public opposition, priests or bishops may be driven by the ambition to show their influence and ability to override public dissent, Cyril Hovorun, director of the Huffington Ecumenical Institute in Los Angeles and former adviser to Patriarch Kirill, told The Moscow Times.

“The apparent lack of dialogue between the Church and local communities is a symptom of the wider problem when the political establishment imposes its will upon citizens,” Hovorun said. “The Church has become a part of this establishment and follows the same behavioral pattern.”

United for the park

The shared fight for Novogireyevo’s remaining green space has brought together individuals from diverse political and religious beliefs. One can find Christians, Muslims, Catholics, Buddhists and atheists at the residents’ meetings and in their group chat, Basya said.

According to her rough estimates from interviews with locals, only 10% genuinely support the church, while about 70% explicitly oppose it. The remaining 20% “aggressively” promote the project, accusing residents of “everything possible.”

“We are accused of being Satanists and collaborators of the enemies of the Motherland. Yet we are simply advocating for life, for the park,” Basya said.

Mikhail said that the majority of church supporters with whom he has argued online turned out to not be from the area. However, when he surveyed residents at the nearby metro station, 95% opposed the church’s construction in the park.

The future of this fight is up in the air. Fear, learned helplessness and personal problems can all impact citizens’ mood, Basya said.

The park defenders said they try not to get disheartened, realizing that much depends on their activism.

“Allies are people who care, who love the city they live in. They join when they realize that otherwise, things will hit rock bottom,” Basya said, adding that they hope for a “peaceful resolution” of the dispute.

“The overall mood is optimistic — nothing has been lost yet, the park hasn’t been cut down or paved over. Therefore, we are drawing attention to our problem with renewed energy,” Mikhail said.

The Moscow government and the Russian Orthodox Church did not respond to The Moscow Times’ requests for comment.