MOSCOW – Longtime Russian human rights campaigner Oleg Orlov told The Moscow Times that he has no plans to leave the country despite facing years in prison for criticizing the war in Ukraine.

The co-chair of Russia’s oldest human rights group, Memorial — which was one of last year’s shared Nobel Peace Prize recipients — is one of a dwindling number of public opponents of the war who remain at liberty inside Russia.

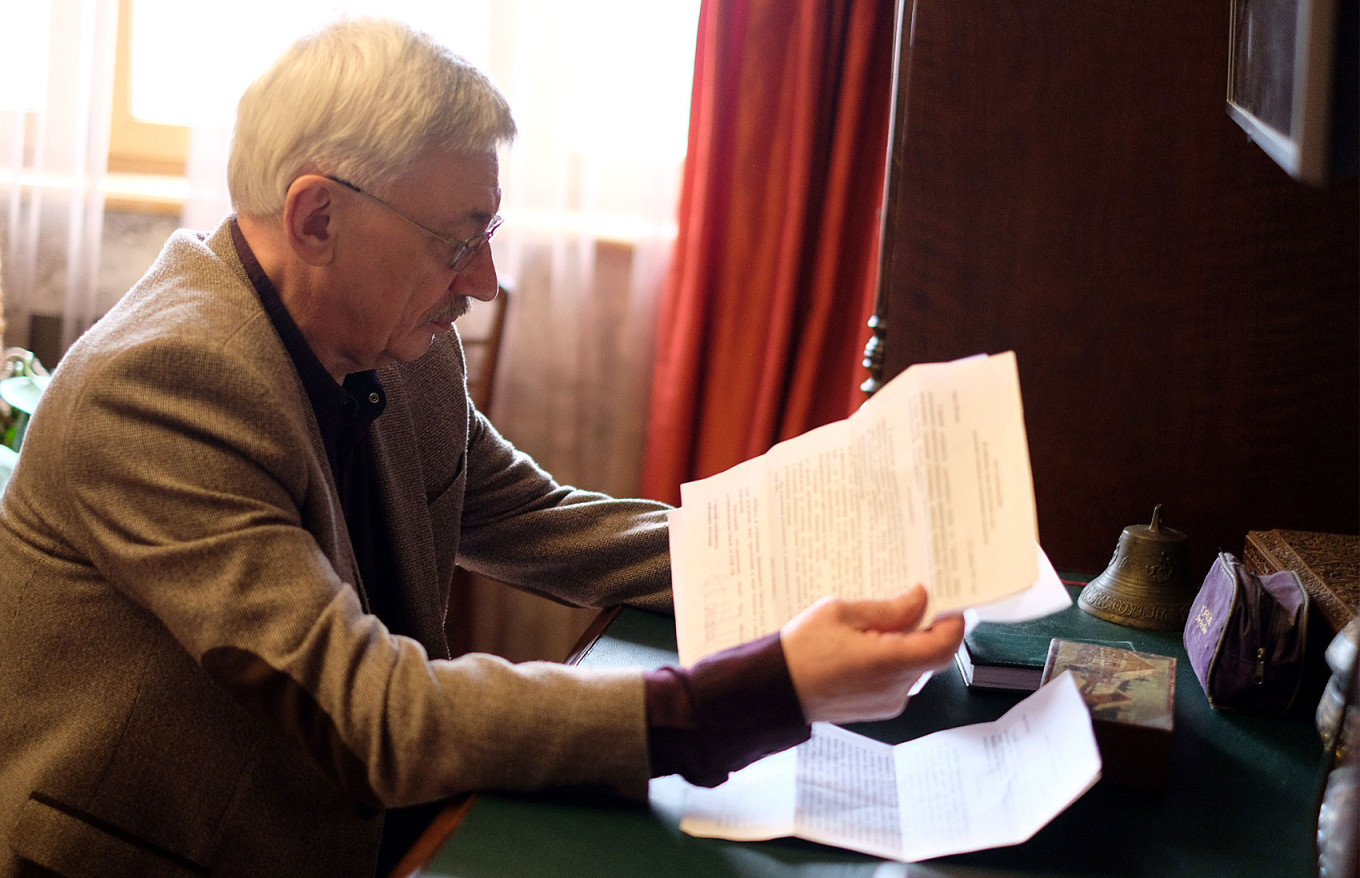

“I am a patriot of my country, even if the authorities view patriotism differently,” said Orlov, 70, during an interview at his Moscow apartment in a quiet residential district.

The door of Orlov’s apartment was daubed with a pro-war “Z” symbol after the February 2022 invasion of Ukraine and the authorities last month opened a criminal case against him under wartime censorship laws.

If found guilty, the former member of Russia’s presidential human rights council could be sent to prison for up to three years.

A widespread crackdown on dissent in Russia has intensified since the Kremlin ordered tanks over the border into neighboring Ukraine and, Orlov said, has included the return of many repressive Soviet-era practices most people thought had been consigned to history.

In addition to political opponents of President Vladimir Putin, the crackdown has increasingly targeted the country’s leading human rights organizations.

Memorial, where Orlov has worked since 1988, was shut down in late 2021 and eight prominent members of the group were targeted in police raids last month. Veteran human rights organization the Moscow Helsinki Group was ordered to shut down by a Russian court in January — the same month as the Sakharov Center, another mainstay of Russian human rights activism, was ordered to leave its premises in central Moscow.

For campaigners like Orlov, who began their activism in the Soviet Union, the war in Ukraine appears to have flung Russia back into its past, with what amounts to a near-blanket ban on opposition activity and the routine silencing of independent voices.

“We understand very well how Soviet activists worked in the U.S.S.R. — to some extent, we are repeating their path,” he said, sitting behind a green baize desk.

“The state is again totalitarian.”

In particular, Orlov pointed out that, over the past 30 years, appeals to state monitoring bodies or the European Court of Human Rights had often yielded results for victims of rights abuses.

“After the collapse of the Soviet regime, Russian human rights campaigners were able to use legal mechanisms, including appeals and requests to Russia’s public monitoring commissions… We could help people,” Orlov said.

But these routes are no longer an option in wartime Russia.

“We are returning mainly to what [Soviet-era] dissidents were doing — collecting information and appealing to the authorities and the public. That’s it… We have been turned into dissidents.”

Russian authorities accuse Orlov, who was released on bail last month, of “discrediting” the Armed Forces based on a Facebook post last year in which he re-posted an article he wrote titled: “They Wanted Fascism. They Got It.”

In the piece, Orlov argued that the invasion of Ukraine is a disaster for Russia and that the Kremlin seeks to use the war as a “unifying” instrument to achieve its political goals.

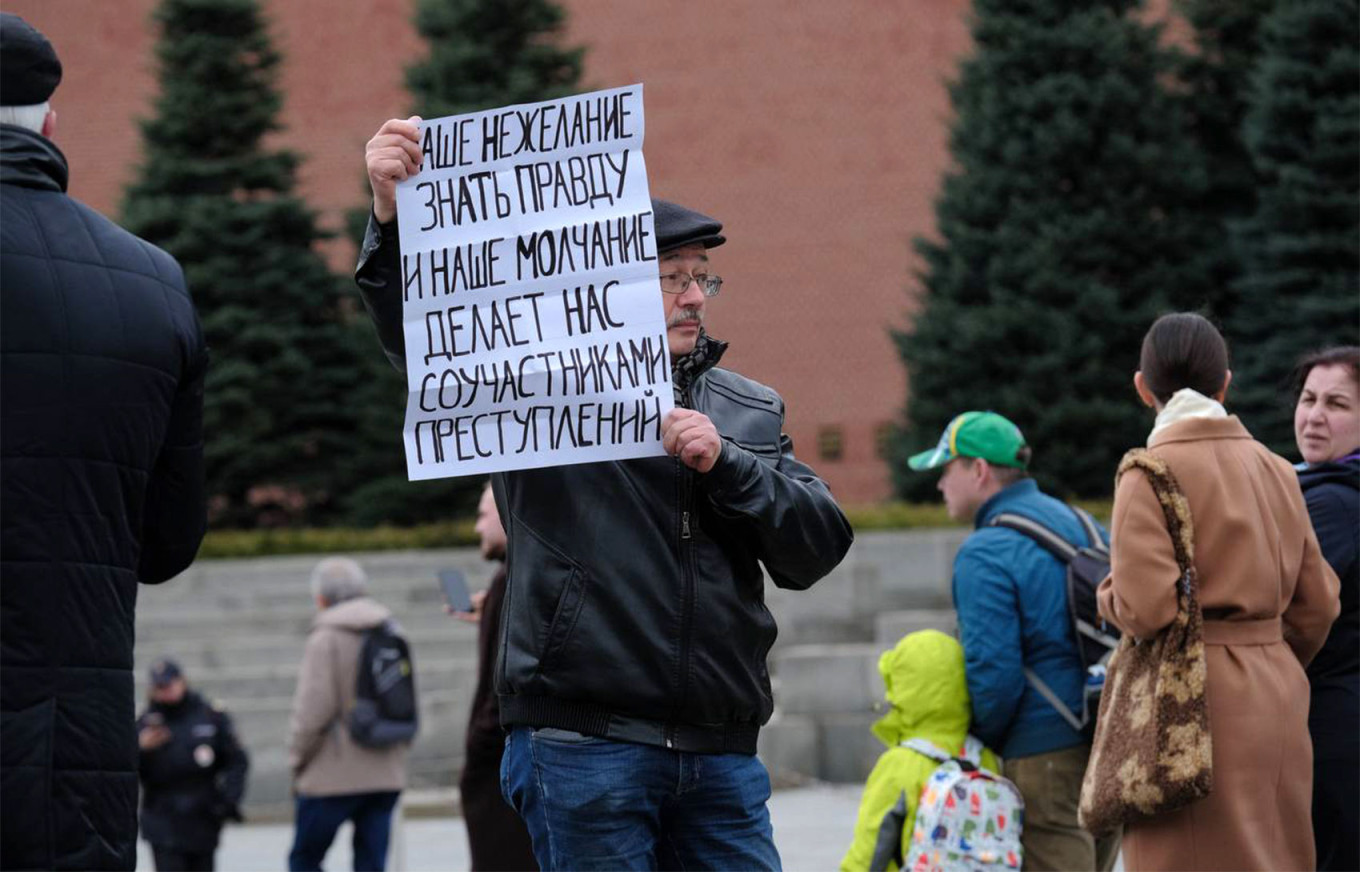

Orlov was also detained last year for a one-man picket on Red Square — where he held up a sign that said: “Our unwillingness to know the truth and our silence makes us accomplices to this crime” — and for another protest against the invasion of Ukraine.

He and seven other members of Memorial were targeted in early-morning police raids last month, ostensibly linked to a criminal investigation against Memorial in which the group is alleged to have carried out the “rehabilitation of Nazism.”

Police claim that Memorial’s database, which lists more than 3 million victims of Soviet repression, contains three names of Nazi collaborators and traitors. Memorial has said it blocked those names from the database.

Orlov said the allegations of “rehabilitating Nazism” against Memorial were designed to “send a signal” to the public and intimidate other activists.

“The authorities get very angry when the public allows itself to raise questions and move forward with a discussion,” said Orlov, referring to the topic of Soviet-era repressions.

As well as human rights activism, Memorial also campaigns for historical justice and has meticulously detailed human rights violations during the Soviet period.

Founded by prominent human rights campaigners, including nuclear physicist Andrei Sakharov, in the twilight of the Soviet Union, Memorial’s two branches were labeled “foreign agents” by Russia’s Justice Ministry in, respectively, 2014 and 2016. They were ordered to close altogether by the Supreme Court in 2021.

In December, Orlov was one of the members of Memorial who accepted the Nobel Peace Prize after it was awarded jointly to Memorial, Ukraine’s Center for Civil Liberties and jailed Belarusian human rights activist Ales Bialiatski.

Despite the pressure on Memorial and the possibility of a jail sentence in the outstanding criminal case against him, Orlov was adamant he has no plans to leave Russia.

“I see myself here since I want to continue the work of Memorial,” he said.

“Why should I leave my homeland?”