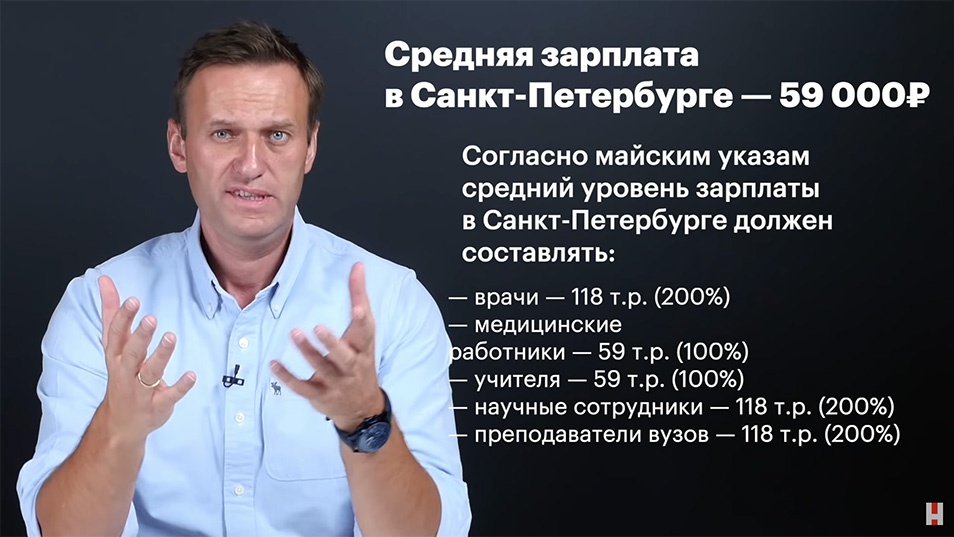

In a YouTube video, opposition politician Alexei Navalny claims state workers’ salaries have remained stagnant despite assurances by the Kremlin.

Alexei Navalny / Youtube

Alexei Navalny’s last stint in prison gave him plenty of time to think. After serving a 30-day sentence in September for organizing protests, the opposition leader was immediately tossed behind bars for another 20 days. He came out in October with an idea.

“We had batted it around for a long time,” says Ivan Zhdanov, director of Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation. “But when Alexei came out of jail, he was practically burning up with it.”

The idea, which became reality last week, was to launch a nationwide, independent trade union. The goal: to ensure that Russia’s state-funded workers — in education, health care and the culture sectors — get the salary increases that President Vladimir Putin formalized through his so-called May Decrees of 2012.

Doctors in the Novosibirsk region of Siberia, for example, were promised an average salary of 69,272 rubles ($1,057) per month. In St. Petersburg, teachers were assured an average salary of 59,000 rubles ($901). These raises were meant to take effect by 2018.

Read More

Russians’ Real Incomes Set to Fall Again in 2019

But current job listings paint a different picture.

In Novosibirsk, a state-funded hospital is looking for a department head at just 23,000 rubles ($351). Listings for teachers in St. Petersburg mostly range from 20-30,000 rubles ($305-458). One even comes in at a whopping 18,000 ($275).

According to Navalny and his team, this is a common state of affairs across the country.

“Our task is to create a spontaneous trade movement, which will have one simple goal — and not a political one,” the opposition leader said in an announcement, though he is explicitly targeting Putin’s core constituency. “We won’t say, ‘Love Putin or love Navalny.’ Love who you want. Just demand a higher salary.”

In 2019, Russians’ real incomes are set to fall for the fifth consecutive year. And with rising consumer inflation, partly due to a value-added tax (VAT) hike from 18 to 20 percent on Jan. 1, Russians have felt their spending power shrink. By targeting salary raises, political analysts say, Navalny has put his finger on the pulse of the burning issue of the day.

Viktor Bartenev / Interpress / TASS

“This is the most valid political demand right now with the most potential political traction,” says political analyst Yekaterina Schulmann.

With a majority of Russians earning low incomes, Schulmann says that Navalny’s move is “politically astute.”

“Ask any political analyst what should be the most influential organization and the most popular party in a country like Russia, and they would all say trade unions and a leftist party,” Schulmann says.

That Navalny is attempting to fight for the little guy has also won him praise among commentators.

Columnist Oleg Kashin described the trade union as “the most promising” political pledge Navalny has made in recent years.

And Abbas Gallyamov, a political analyst and former Kremlin speechwriter, goes as far as calling it a “potential threat” to the current administration.

Read More

As Putin Sails to Six More Years, Navalny Eyes the Long Game

Doubters, however, question whether the politician can pull it off.

“It’s not clear yet what Navalny is actually offering,” says political analyst Gleb Pavlovsky. “A trade union is concrete work, not a movement. For now, it just looks like a statement of intent.”

What prospective patrons of the union are currently offered, beyond a statement of intent, is a website. There, visitors to the site begin by selecting their job and the region in which they are based. Then they are prompted to respond “yes” or “no” to whether the salary they are receiving corresponds to the official standard according to Putin’s decrees. If they select “no,” they are provided with a form to input their personal information which Navalny’s team of lawyers at the Anti-Corruption Foundation will use to file complaints to local authorities.

The idea isn’t new for Russia, which has a long history of trade unions since the Soviet Union. But Navalny’s team claims that what will set theirs apart is that others tend to toe the party line.

“Our trade unions have never functioned as actual trade unions,” says Zhdanov, who is responsible for the day-to-day workings of the project. “So we are planning to figure it out as we go.”

Read More

The Looming Russian Recession (Op-ed)

That process has begun. Already, the Anti-Corruption Foundation, which has made a name for itself by publishing investigations of corruption by high-profile state officials, is working with the Alliance of Doctors workers’ collective to help fight for increased salaries for medical workers, Zhdanov said. He pointed to a series of videos for the group about doctors’ low wages as a sign that Navalny’s entire team is rallying around the project.

“We see this project as our main task going forward,” Zhdanov said.

At the moment, Zhdanov’s team has six lawyers in Moscow and campaign offices in some 38 regions leftover from Navalny’s failed presidential run in 2018 that will serve as the spine of the project. Zhdanov is planning to hire two more lawyers for the central Moscow headquarters and for regional office coordinators to attract local lawyers to the cause.

“Seventy-five percent of this initiative is legal work,” he explained.

Such labor, while perhaps less glamorous than outspoken political critique, will attract Navalny a new audience, Gallyamov believes.

“For people who didn’t like him, didn’t care about the topics he discusses like corruption and independent elections, or didn’t have any real complaints against the authorities,” says the political analyst, “he is suddenly appealing because he is helping them with the issue they really care about.”

Despite the government’s relentless pressure on Navalny, Gallyamov sees the trade union as a particularly well-timed play. He points to losses by four Kremlin-backed gubernatorial candidates in September despite being up against so-called “spoiler” candidates as an indication of the fragility of the support for the status quo.

If there is mass dissatisfaction to come, Gallyamov believes Navalny is presciently laying down effective groundwork. “By collecting all of these people’s information,” Gallyamov says, “he is tapping into a potentially vast support base.”