Ten days since launching its surprise incursion into Russia’s Kursk region, Ukraine controls over 1,100 square kilometers of Russian territory.

The attack has caused consternation in the Kremlin, changing the cadence of the fighting from a sluggish positional war to a new bout of emotionally charged confrontation which may have repercussions beyond the military state of play.

Among the widely discussed consequences of Ukraine’s offensive are the economic effects.

A middling region in terms of gross regional product — just $7.5 billion, or five times smaller than that of Moscow — Kursk is nevertheless disproportionately important to the Russian economy in several ways, including its role as a gas transit point to Europe via Ukraine.

Most importantly, Ukrainian forces wrested control of the town of Sudzha and its outskirts, including the gas metering station (GMS) just 300 meters from the border through which the fuel passes into Ukrainian territory and then to European buyers, including Austria, Hungary and Slovakia.

The station is one of the five GMSs in the region, but is the largest and best equipped.

Despite early panic, the gas continues to flow through Sudzha, with neither Ukraine nor Russia announcing intentions to cut off the supplies.

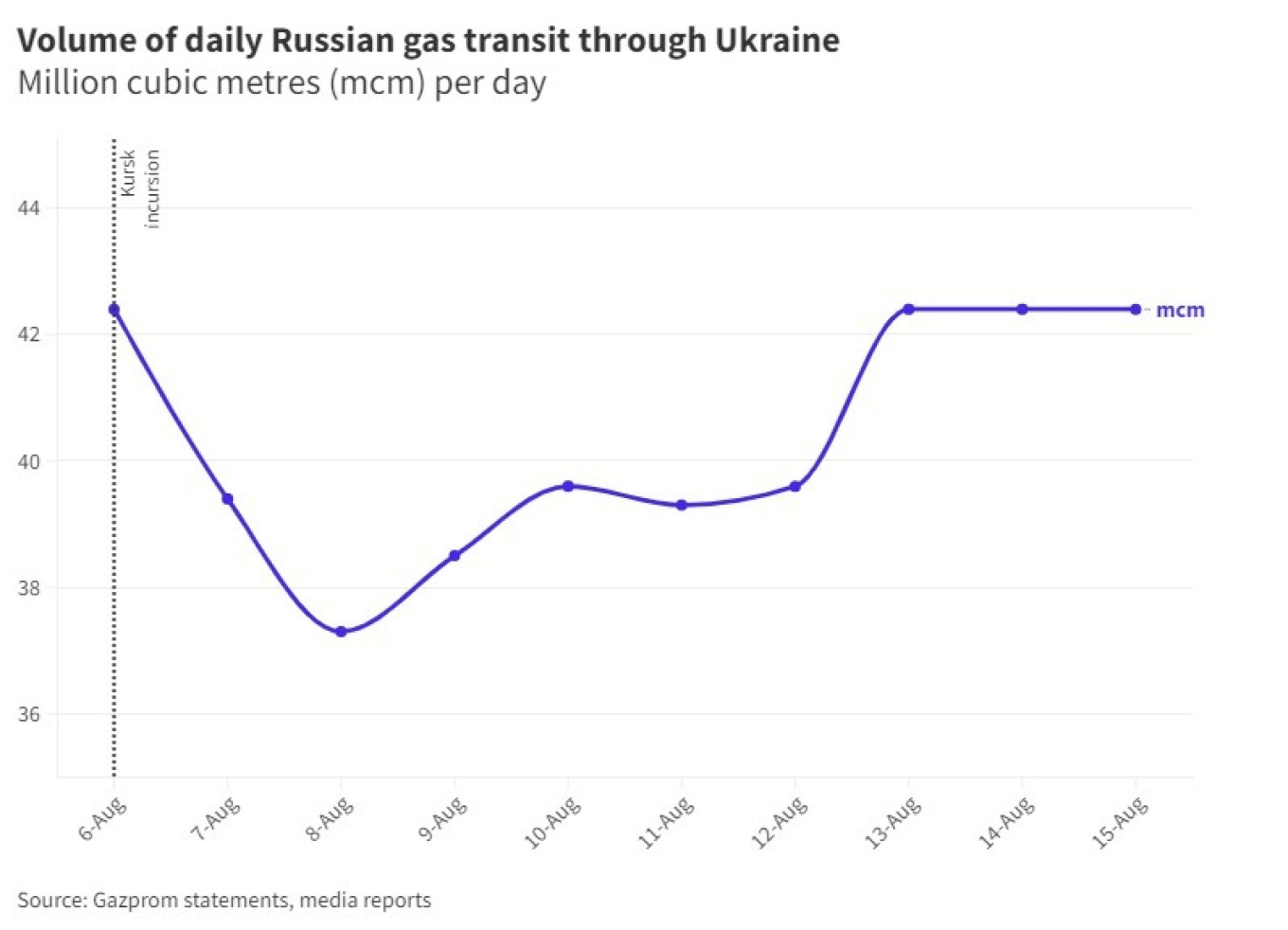

As of Thursday, the volume of Russian gas transit through Ukraine was estimated at about 42.4 million cubic meters per day compared to the August average of 41 million cubic meters, Gazprom said.

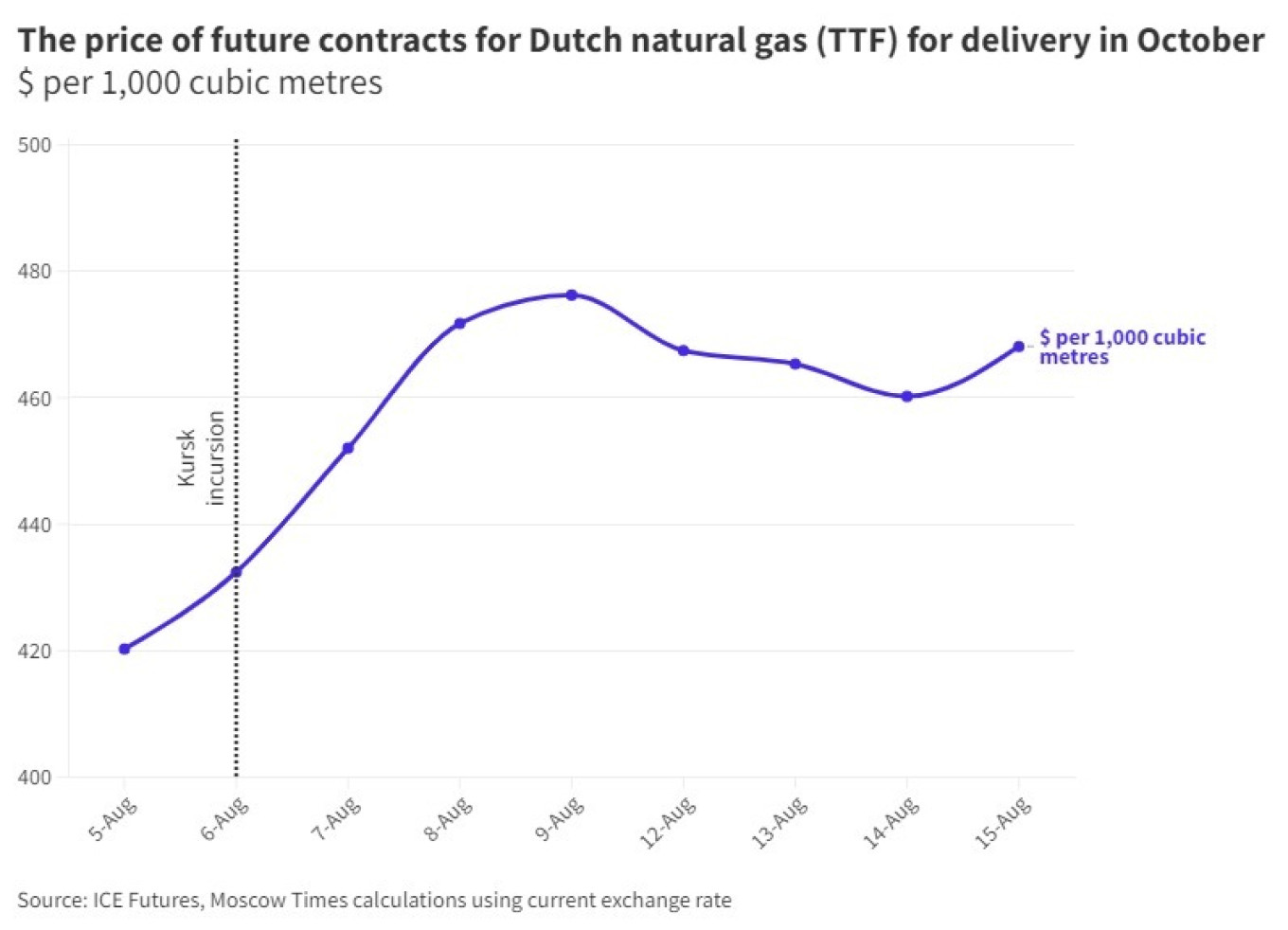

The proceeds from the transit deal, although modest at about $800 million, help Ukraine maintain its transport system while keeping a lid on European gas prices. According to analyst Sergei Kaufman and the independent Meduza website, the transit ban would cause spot prices for gas to rise by about 20%.

On the Russian side, the benefits of continued transit are also fairly straightforward. In 2023, Ukraine transit route accounted for about half of what little gas Russia still shipped to Europe bringing about $7-8 billion in revenues.

For Gazprom, Ukrainian transit supplies account for about 15% of its profits, something it would want to avoid.

Another key installation close to the fighting — the Kursk nuclear power plant — also appears to be out of danger.

Finally, the Kursk region lies at the heart of the fertile agricultural area known as the Black Belt.

In total, Kursk contributes 2.7% of the country’s agricultural production, according to official data for 2023. It accounts for about 14% of the oilseeds agricultural land and 11% of the cereals land in the Central Federal District, which includes the traditional agricultural regions of Voronezh and Belgorod.

Yet most of the region’s major facilities — such as the Kursk meat processing plant, the Artel agricultural company and the Agroproduct grain processing company — are beyond the reach of the fighting.

Natalya Goncharova, Kursk’s acting agriculture minister, said on Wednesday that the region’s grain and oilseed harvest was continuing.

The actual direct impact on the Kursk region’s harvest is minimal, Andrei Sizov, head of the Sovecon agricultural consultancy, said on his Telegram channel.

Ukraine controls only a few percent of the Kursk region’s total area — about 700-1,000 square kilometers of the total 30,000 kilometers — while the harvest of a significant part of the crop is almost complete, Sizov explained.

Wheat, for example, has been harvested on more than 90% of the region’s land, he added.

As a result, the Kursk incursion turns out to be of minor importance in terms of its direct military and economic impact, but its political outcome widens the scope for the conflict to ramp up.

For one thing, the Kursk incident could trigger a “new round of escalation,” potentially pushing up wheat prices, Sizov said.

This scenario could materialize if trade in the Black Sea, a key shipping route for agricultural products, is disrupted again.

For example, Chicago wheat rose on Thursday following an overnight Russian attack on the Ukrainian Black Sea grain export port of Odesa, Reuters reported on Thursday.

Likewise, while cutting off Ukraine’s gas transit seems like a lose-lose situation, there is no guarantee that it won’t happen.

The losses may be manageable for both sides in the medium term, but it would sever the remaining economic link between Russia and Europe, increasing the potential risks of an all-out confrontation, including both sides stepping up strikes on each other’s energy infrastructure.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia’s Prosecutor General’s Office has designated The Moscow Times as an “undesirable” organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a “foreign agent.”

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work “discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership.” We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It’s quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you’re defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Once

Monthly

Annual

Continue

Not ready to support today?

Remind me later.

×

Remind me next month

Thank you! Your reminder is set.