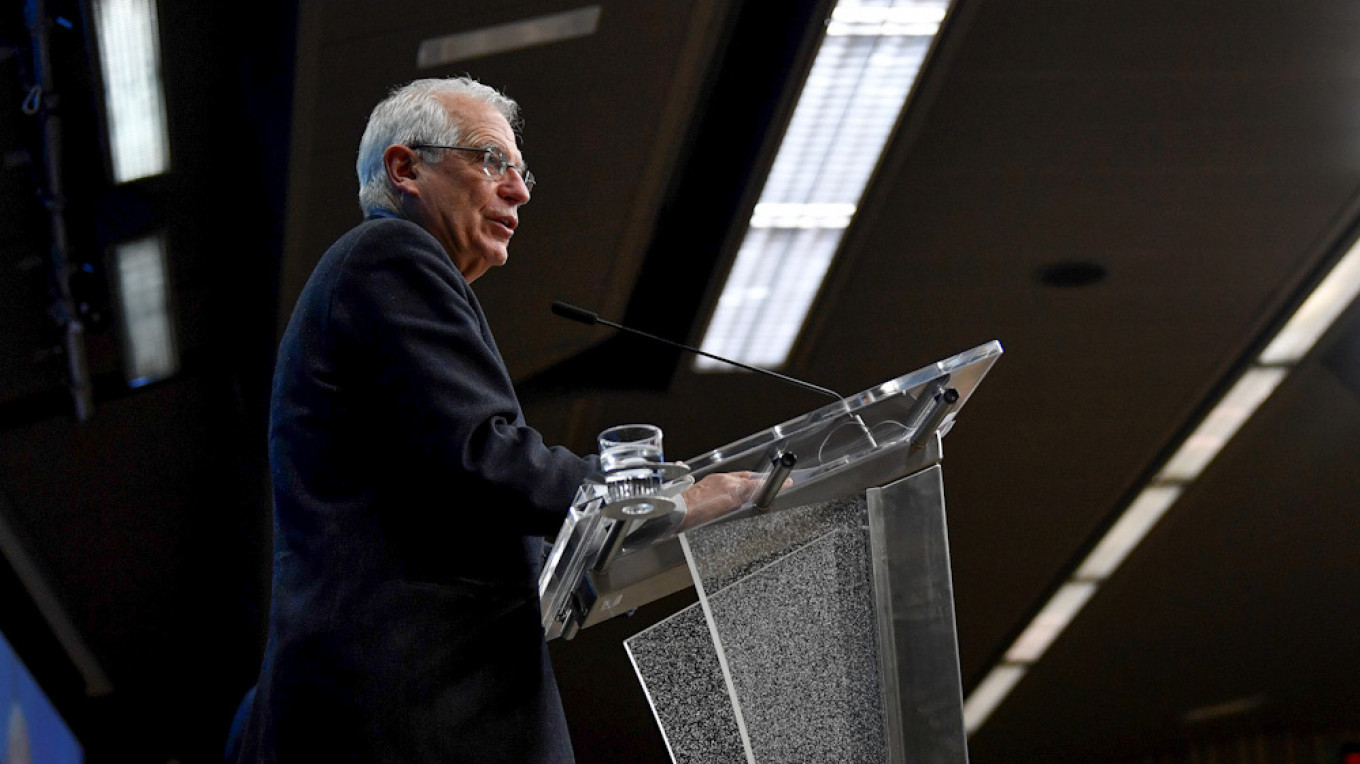

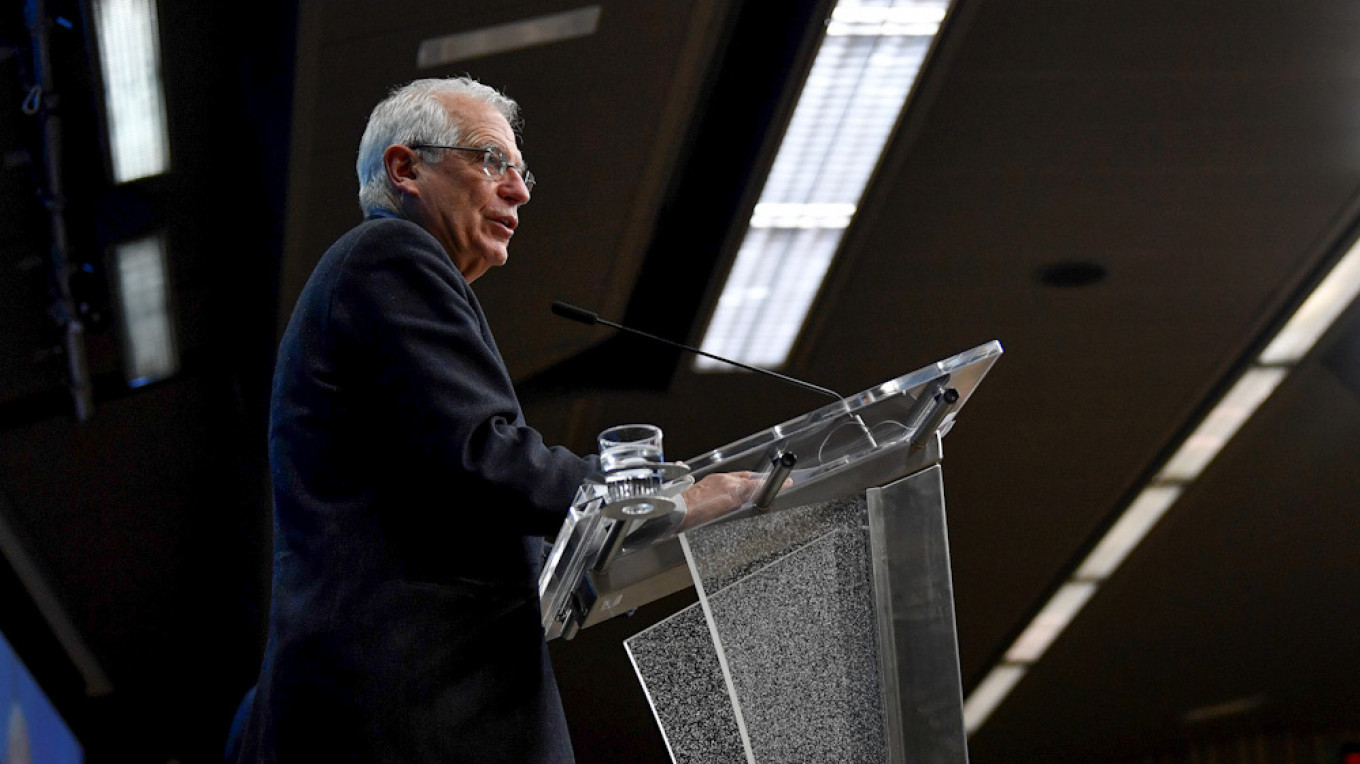

EU foreign policy chief Josep Borrell jets to Moscow on Thursday under pressure to confront the Kremlin over the jailing of Alexei Navalny and a crackdown on protesters.

The visit — the first to Russia by a top EU envoy since 2017 — has drawn criticism from some European capitals worried Moscow will spin it as evidence Brussels is keen to return to business as normal.

But Borrell insists he will deliver “clear messages” to the Kremlin despite it blanking Western calls to release President Vladimir Putin’s most prominent domestic opponent Navalny, who was on Tuesday given a jail term of almost three years.

“It is when things are not going well that you must engage,” the former Spanish foreign minister said on Monday.

The EU’s ties with Russia have been in the doldrums since Moscow seized Crimea and began fueling the war in Ukraine in 2014 — and there are concerns about its involvement in Belarus, Syria, Libya, central Africa and the Caucasus.

Borrell is eager to sound out his veteran counterpart Sergei Lavrov on the chances of cooperation on issues including enlisting Russia’s help in reviving the Iran nuclear deal and tackling climate change.

But it will be the jailing of Navalny and detention of thousands of demonstrators across Russia by baton-wielding security forces that dominates his visit.

Nonsense, says Kremlin

The EU foreign policy chief is under no illusions that he can pressure Moscow into freeing Navalny — and the Kremlin has already warned him off.

“We hope that such nonsense as linking the prospects of Russia-EU relations with the resident of a detention center will not happen,” Putin’s spokesman Dmitry Peskov said.

Moscow stands “ready to do everything” to develop ties with Brussels, but the Kremlin is “not ready to listen to advice” on the issue of Navalny, he said.

The authorities have poured cold water on attempts to set up a meeting with Putin’s nemesis and Borrell will settle for talks with civil society representatives.

Back in Europe calls are growing from some nations for the EU to bulk up on sanctions it slapped on six Russian officials in October over the nerve agent poisoning that left Navalny fighting for his life in Germany.

EU foreign ministers last week agreed they would revisit the issue if he was not released.

“After this ruling, there will now also be talks among EU partners. Further sanctions cannot be ruled out,” said German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s spokesman Steffen Seibert.

An EU statement said foreign ministers would discuss “possible further action” at a meeting on Feb. 22.

Navalny himself called at the European Parliament last year — two months before his fateful return to Moscow — for sanctions to hit the oligarchs and money-men he accuses of protecting Putin’s wealth.

But European diplomats say that any measures, if they come, would likely just target officials and functionaries directly involved in the clampdown.

There have also been calls for Germany to halt the highly contentious Nord Stream 2 pipeline project to bring Russian gas to Europe.

Continental powerhouse Berlin has rebuffed the clamor and Borrell insists Brussels has no power to make Germany pull the plug.

“I don’t think that it is the way to resolve the problem with Navalny,” Borrell said.

“The Russians won’t change course because we tell them we will stop Nord Stream.”

For Moscow the visit looks set to be used as a chance both to deflect from its own issues and show that the West still wants to talk to it regardless.

‘Not a sign of weakness’

“On the one hand, the Kremlin is eager to portray the EU as a weak actor with a lot of internal problems,” said Susan Stewart from the German Institute for International and Security Affairs.

“On the other hand, despite official rhetoric, the Kremlin is still keen to demonstrate that western actors are interested in cooperating with Russia, since this increases its status and legitimacy.”

But with European leaders set to debate their overall approach to Russia at upcoming summits in the next few months, diplomats in Brussels insisted this was the right time to visit Moscow.

“There are reasons to go there to pass on messages,” one European envoy said.

“This mission is not a sign of weakness.”