At a March council meeting in the Russian city of Voronezh, local deputy Nina Belyaeva condemned her country’s invasion of Ukraine and described the Russian military’s actions as a war crime.

Within weeks, she was accused of “spreading false information” about the army — a violation of wartime censorship laws that can lead to a long jail sentence.

Belyaeva, 33, avoided arrest and fled to neighboring Latvia. Since then, she has not only been arrested in absentia by the Russian authorities, but was last month added to a terrorism list for criticizing Russian President Vladimir Putin.

“When you understand the scale of the bombings, you cannot remain silent,” the deputy from Russia’s Communist Party told The Moscow Times in a phone interview. “I heard aircraft noise [in Voronezh] and I knew that the civilian airport was closed — I knew that any flying aircraft was a military one.”

Over six months since the start of Russia’s invasion in February, thousands of people have been charged under laws punishing criticism of the war. But there appears to be little logic behind prosecutions and it is not just opposition figures and politicians on the receiving end — journalists, artists, musicians, school teachers, archaeologists, DJs, doctors and single mothers have also been targeted.

In total, Russia has opened more than 3,800 administrative cases for “discrediting” the Russian army since censorship laws were passed in March, according to the OVD-Info protest monitoring group.

More seriously, there are dozens of active criminal cases for repeatedly “discrediting” the Armed Forces and at least 90 criminal cases have been opened for “spreading false information,” OVD-Info said.

The punishment for those found guilty of “discrediting” the Russian Armed Forces is a fine of up to 1 million rubles ($16,467), with repeat offenders liable for prison sentence of up to five years; while those convicted of “spreading false information” can be sentenced to up to 15 years in prison.

Like Belyaeva, many Russians have left the country due to the threat of long jail terms.

Facing up to three years in prison for “spreading false information” about the Russian army, Siberian regional assembly deputy Helga Pirogova fled to neighboring Georgia last month.

Pirogova, 33, was charged over a since-deleted tweet criticizing the mother of a dead Russian soldier who praised the authorities over arrangements for her son’s funeral.

In a recent interview, Pirogova said a criminal case was the only thing that “could squeeze her out” of the country.

“I didn’t want to leave Russia. I still don’t want to and, to say the least, I can’t make peace with it. I have no desire to,” she told media outlet Meduza.

But activists and those involved in politics are not the only ones to have been targeted under the new laws.

Sometimes, those charged have not even made anti-war statements.

Alexei Argunov, a philosophy and history teacher from the Siberian city of Barnaul, was fined 30,000 rubles ($484) last month for “discrediting” the Armed Forces after reacting to a post on Russian social network Odnoklassniki with an emoji.

Argunov put emojis under three war-related posts, ironically adding a sad smile under news about a local official who was fined for stating his opposition to the Russian invasion.

“It’s dangerous to express your opinion. People are not safe,“ Argunov told The Moscow Times in a phone interview.

In other examples, teacher Irina Gen, 45, received a five-year suspended sentence earlier this month for “spreading false information”; a DJ in Russian-annexed Crimea was jailed for ten days for “discrediting” the army after playing a Ukrainian song in a karaoke bar; archaeologist Yevgeny Kruglov, 46, was arrested after being accused of “spreading fale information” on social media; and Dmitry Chistyakov, a former spokesperson for Russia’s Emergency Situations Ministry, faces a fine of up to 50,000 rubles ($826) for “discrediting” the Armed Forces. Russian Orthodox theologian Andrei Kuraev was fined 30,000 rubles ($484) this week under the same law.

While these censorship laws have been used many times, there is still much uncertainty surrounding the exact definition of “discrediting” the Armed Forces and “spreading false information.”

Russia’s Justice Ministry apparently has compiled a special guide stating that “a negative opinion” is viewed as “discrediting,” while “a statement of fact” is considered to be “spreading false information,” the Kommersant newspaper reported earlier this month.

Either way, the laws appear to have been designed to be vague enough that almost anyone can be targeted.

“We can definitely say that the laws are military censorship,” said Alexandra Baeva, the head of the legal department at OVD-Info. “Spreading any information that contradicts Russian official statements [about the situation in Ukraine] is punishable.”

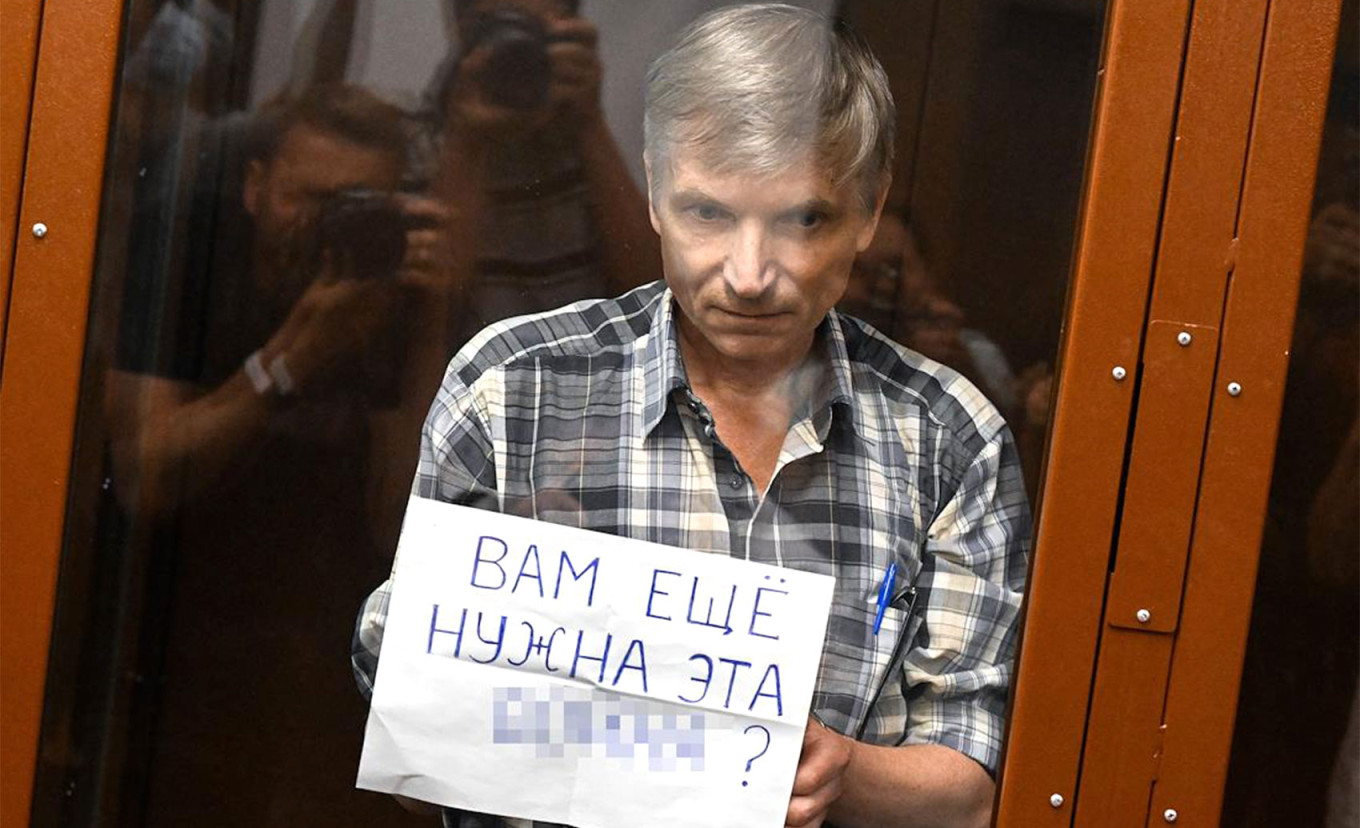

The first person to be sentenced to a long jail term under the wartime censorship laws was Moscow municipal deputy Alexei Gorinov, who was given seven years in prison last month.

Gorinov’s crime was to question whether it was appropriate to hold an art competition for kids in his constituency while — as he put it — “children are dying” in Ukraine. He denied his guilt and held up a placard in court that read: “Do you still need this war?”

Opposition leaders Ilya Yashin, 39, and Vladimir Kara-Murza, 40, who were arrested for allegedly “spreading false information” about the Russian army, are currently in jail awaiting trial.

The former mayor of Yekaterinburg and another prominent Kremlin critic, Yevgeny Roizman, was detained Wednesday on criminal charges for repeatedly “discrediting” the Russian Armed Forces.

Along with politicians, journalists are also one of the largest groups to have been targeted, with at least 14 criminal cases for “spreading fakes” about the Russian Armed Forces opened against reporters, according to lawyer Stanislav Seleznyov, a senior partner at the Net Freedoms Project.

Russia’s Interior Ministry placed investigative journalist Andrei Soldatov on the federal wanted list after he was accused of “spreading false information” in March. Journalists Alexander Nevzorov and Michael Nacke and Conflict Intelligence Team founder Ruslan Leviyev have all been accused under the same law.

In total, over 200 people are currently facing criminal prosecutions for voicing opposition to the war in Ukraine, according to the tally kept by OVD-Info.

These criminal and administrative prosecutions have gone a long way toward silencing criticism of Russia’s actions in Ukraine, according to Seleznyov.

“Every news report about yet another criminal case or fine for discrediting the army and spreading false information cools public discussion,” he said.

Yet despite the unprecedented crackdown, Russians continue to oppose the war.

“It was unbearable for me to understand that people [in Ukraine] were being killed and maimed and I couldn’t do anything,” Belyaeva said from Latvia.

“At least I could speak out.”