“Will I be able to shoot at my comrades?”

Vlad was tormented by this question during the events of June 24, as a convoy of rebel mercenaries led by Wagner Group leader Yevgeny Prigozhin advanced on Moscow and Russia seemed on the brink of civil war.

A former Wagner fighter, Vlad, who asked that his name be changed for security reasons, is now serving in the Russian military — hence his fear that he could have been sent to defend the capital from his former comrades-in-arms.

Following the mutiny, which ended in a deal for Prigozhin and his men to go to exile in Belarus, four former and current Wagner fighters who spoke to The Moscow Times shared mixed views toward the rebellion and its impact on the private military company’s future.

Like other former mercenaries, Vlad, 29, blamed Prigozhin for pitting Russian soldiers against each other to gain the upper hand in his personal feud with Russia’s Defense Ministry.

“I would never have allowed myself to point weapons at our own people and, in a certain sense, against our own country,” said Vlad, who said he enlisted in Wagner to “defend his country” and not “out of sympathy for Prigozhin.”

“My comrades and I fought for the country, not for some bold idiot and his personal ambitions,” said Roman, 35, another former Wagner mercenary from Moscow.

Roman had decided to leave his job in finance last year and enlist with Wagner out of a sense of “civic duty.”

“My country is at war and I cannot stand on the sidelines,” said the former mercenary, who served nine months on the front line in Ukraine, advancing with his unit from Popasna to Bakhmut. For his service, he was awarded the black cross, one of Wagner’s military awards.

After years of operating in the shadows in global conflict zones — and earning a reputation for brutal tactics and rights abuses — the Wagner Group and Prigozhin took on a highly public role in the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Both Roman and Vlad said they were shocked when Prigozhin declared an armed uprising against Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu and ordered the occupation of the southern city of Rostov-on-Don.

Though they did not agree with Prigozhin’s rebellion, they also blamed the military’s top brass for allowing the conflict with Wagner to escalate to that point.

“Because of their inattention, the best-prepared military unit in our country suffered,” said Vlad, referring to the “reputational damage” inflicted on Wagner by Prigozhin’s mutiny.

“If my iron cross used to make me 100% a patriot, now I’m half patriot and half traitor,” Roman said.

While the uprising was aborted in less than 24 hours, it still took a heavy toll: some 15 Russian soldiers were killed, including some pilots, and several military vehicles were destroyed.

“Our comrades killed each other, a huge amount of military assets were destroyed, people are scared, not to mention the damage to Russia’s reputation on the geopolitical stage,” said Roman, who criticized Prigozhin’s mutiny for failing to achieve any concrete goals.

“The ‘parquet’ generals are still there,” Roman said, referring to the corrupt and ineffective military leaders whom Prigozhin supposedly aimed to take down.

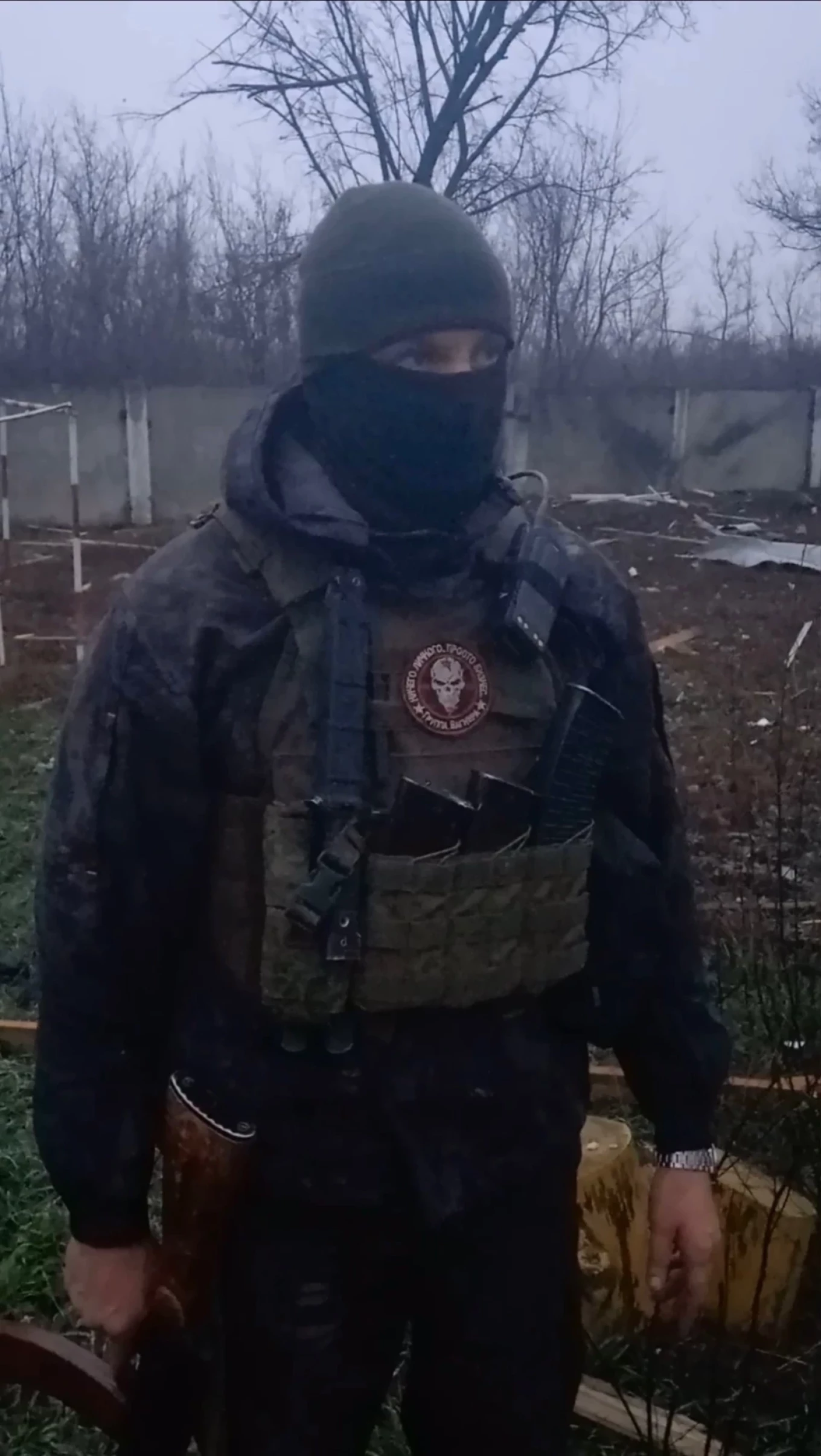

Unlike Roman and Vlad, other former mercenaries said they remained fully loyal to Prigozhin, such as Malik, 29, who, just one week after the coup, walked down Nevsky Prospekt in central St. Petersburg wearing a cap and T-shirt bearing the Wagner skull logo.

“It’s not forbidden; I remain a patriot of my country,” said Malik, also a veteran of the battle for Bakhmut, commenting on his outfit. On his arms, wounds inflicted by shrapnel have just healed.

“The whole of Rostov supported Wagner and Prigozhin,” the former mercenary claimed. “Prigozhin talks and acts rightfully, he has done a lot for the country, while I don’t think Shoigu has ever done anything useful.”

Some mercenaries said they still hoped that, despite failing to achieve any immediate results, Prigozhin’s mutiny would lead to a reshuffle of the country’s military leadership, which they accused of corruption and incompetence.

“I hope that the ‘march for justice’ worked as a warning bell for our government, that they saw that the time is ripe for changes,” said Mikhail, 32, another Wagner mercenary, using Prigozhin’s definition for the uprising.

A former factory worker from central Russia, Mikhail has been part of the Wagner Group since 2020, serving in the Central African Republic and Ukraine.

While he criticized Prigozhin’s mutiny for being “too radical,” Mikhail’s admiration for the Wagner leader hasn’t diminished since the attempted coup, and he said he “remains the leader of the world’s best military organization.”

The Wagner Group’s fate now appears uncertain. In the days following the attempted mutiny, the recruitment of mercenaries for the war in Ukraine appeared to continue as usual in several Russian regions. Recruitment pages reappeared on the Russian social network VKontakte after being taken down during the mutiny.

But as the head of the State Duma Defense Committee, Andrei Kartapolov pointed out, Wagner will now have to sign a contract with the Defense Ministry or it will lose state funding and will no longer be able to participate in the war in Ukraine.

On July 2, Wagner announced that its regional centers were halting recruitment for one month due to Wagner’s “temporary non-participation” in the war in Ukraine and its “relocation to Belarus.”

For Mikhail, nothing has changed for his unit so far. He and his comrades were offered to sign up with the conventional army, but they “were not forced” to do so and he doesn’t intend to.

He plans to return to his unit once he recovers from his wounds.

“It doesn’t matter where we are located, the Wagner PMC remains a Russian company defending Russia’s interests,” says Mikhail. “We’ll head wherever they tell us to go.”