Mikhail Mishustin was struggling. Drenched in sweat and tripping over himself, he wasn’t a natural ice hockey player.

“I don’t know whether he’d played before, but it was clearly very hard for him,” Dimitri Elkin, CEO of Twelve Seas Investment Company, said of the man just named Russia’s new prime minister. “He’s not the most athletic guy; he’s a bit on the heavy side. But he just kept going, and I was like: Wow, this guy has some willpower.”

The year was 2009. Like Elkin, Mishustin, now 53, was a managing partner at the Moscow-based investment group UFG Asset Management. Two years earlier, Mishustin had also begun organizing exhibition hockey games that were attended by some of Russia’s most powerful people.

The games were a precursor to a more formalized league that President Vladimir Putin would create in 2011: the Night Hockey League. In ensuing years, it would become a fraternity for Russia’s elite, like golf in the U.S. As political analyst Andrei Kolesnikov told AFP last week, the league has become “like a masonic lodge.”

“I have no doubt that him being there — being one of the boys — was a factor in him getting where he is now,” said Elkin. “Mikhail is really good at knowing who the right people are.”

When Putin appointed Mishustin to head the Russian government earlier this month, after setting into motion what appears to be a succession plan with a raft of proposed changes to the Constitution, the move came as a surprise. Having spent the past decade serving as Russia’s tax chief without voicing any greater political ambitions, Mishustin was quickly labeled a technocratic placeholder.

If Mishustin has aims beyond the role of prime minister, they have been difficult to tease out. But interviews with nearly two dozen of his acquaintances, business associates, former classmates and colleagues paint a more nuanced picture: one of an ambitious figure who knows how to work the system and has always put himself in position to climb up the next rung on the ladder.

As the dust has settled in recent days, some political analysts are wondering if the little-known systems engineer might be in the running to be the successor to the man who has ruled Russia for the past two decades.

“Mishustin is certainly not a placeholder prime minister, but a fully-fledged member of the cast of successors for the role of president,” Alexander Baunov of the Carnegie Moscow Center wrote on Facebook. “His relative obscurity should not exclude him. Vladimir Putin himself was a little-known official until the moment [Boris] Yeltsin appointed him to three high posts one after another.”

Natural networker

Born and raised just outside the Russian capital, Mishustin completed a degree in systems engineering at Moscow State Technological University in 1989. Former classmates remember him as gregarious, someone around whom social life would orbit.

“He had many friends and always liked being in a group,” said Andrei Morozov, a Moscow-based IT consultant who graduated the same year.

After staying on to complete a graduate degree in 1992, Mishustin found work with the International Computer Club. Formed by a group of Soviet scientists in 1986 with the approval of the KGB, the non-profit organization was the first to bring Western technology to the Soviet Union. When the Iron Curtain fell in 1991, the floodgates opened.

“Basically, it was a marketing operation designed to get Western computer companies to invest in Russia — which they did to very good effect,” said Esther Dyson, a Swiss-born American investor who worked with the group at the time.

The main way the International Computer Club did this was by bringing professionals together through an annual three-day conference called Russkiy Den’, or Russia Day, held around the national holiday in mid-June. Originally hosted in Moscow, it moved to the Black Sea resort of Sochi in the late ’90s, running annually until 2015.

Photos from early gatherings show what looks like a typical industry convention anywhere at the time: waitresses in skimpy outfits, tables stacked with bottles, men singing karaoke.

The conference brought together around 150 leaders of Russia’s burgeoning tech industry. Key players included Arkady Volozh, the billionaire founder of Yandex; Anatoly Karachinsky, the founder of the IBS group, Russia’s largest computer company; and Olga Dergunova, current Deputy President at state bank VTB, among others.

In addition to top business leaders, the conference attracted high-placed government officials.

“It was a democratic space,” said Yegor Yakovlev, founder of Tvigle, Russia’s first online streaming service. “We don’t really have that anymore.”

Tight connections

In the early ’90s, Mishustin became close with one high-placed government official in particular: Boris Fyodorov, Russia’s first finance minister.

“It’s no secret that he was tight with Boris Fyodorov, that he was his guy,” said Sergei Aleksashenko, who served as Fyodorov’s deputy at the Finance Ministry from 1993 to 1994.

In 1998, Fyodorov, who by then had become Russia’s tax chief, handed Mishustin his first role in government as his aide in charge of information systems.

Although Mishustin left the private sector for the public sector, he continued attending Russkiy Den’ until 2012, according to the International Computer Club’s website, and was a keynote speaker in later years. He also invited more government officials, say regular attendees.

“It was an opportunity to talk openly behind closed doors about what was affecting the industry,” said Rustem Khayretdinov, deputy general director of InfoWatch, who attended the conferences regularly. “Problems like the over-reaching of the siloviki” — officials with ties to law enforcement.

But if Fyodorov was an openly liberal reformer, those who knew Mishustin in those years said he never discussed his politics.

“We didn’t talk politics back then,” said George Pachikov, founder and CEO of Cortona3D and a friend of Mishustin’s from the time. “We had defeated the main enemy, the communists, and we firmly believed we were on the path toward joining Europe and becoming part of civilization.”

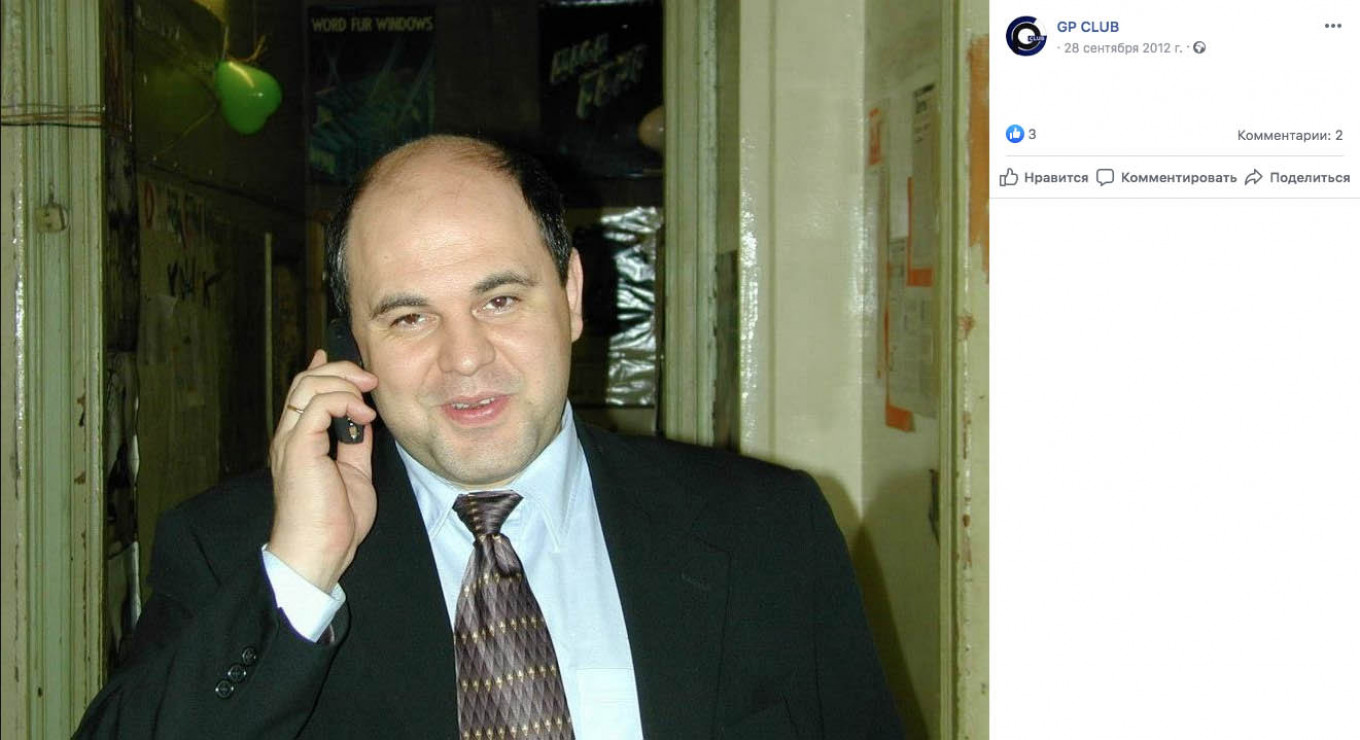

Pachikov and Mishustin had grown close through another social group: GP Club, named using Pachikov’s initials. A more informal gathering of the IT community who’s who, the group met on Thursday evenings in an office in central Moscow and at members’ houses on special occasions.

The group still retains a Facebook page, featuring photos of its events. Mishustin, who has written several songs for popular Russian singer Grigory Leps, is pictured singing, dancing, playing the piano and draping his arms around friends.

“It was a small group of progressive like-minded thinkers,” said Marat Guriyev, former director of government relations for Samsung in Russia, and a member of the club.

Guriyev, who served for four years in Boris Yelstin’s presidential administration, described Mishustin as one of the group’s leaders and “arguably the smartest of our crew.”

“The mentality of the club was liberal, pro-Western, pro-open internet,” Guriyev added. “That was the spirit of the time. Those were the days of freedom.”

Ruling staples

In 2008, Mishustin’s key connection Fyodorov brought him into another new world: finance. He offered Mishustin a role at UFG Asset Management, a financial firm he had co-founded with Charles Ryan, an American investor.

Mishustin didn’t immediately fit in. He would “curse like a sailor,” one former colleague at the firm recalled, asking to remain anonymous. And, according to Elkin, he sometimes wore a black shirt with a black suit, sticking out among the conventional investors. Still, he played a key role.

“He was quite helpful in making various introductions to Russian oligarchs,” Elkin said. “He was more of a political figure.”

In 2008, Fyodorov, who was now living in London, died from a sudden stroke, but Mishustin was already forging out on his own.

A year earlier he had launched a hockey tournament that included members of the political establishment, including Sergei Naryshkin, now the director of Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service. Mishustin continued organizing the competition after he moved to UFG Asset Management in 2008, and the firm became its official sponsor the next year.

With each year, the exhibition hockey games attracted increasingly more powerful people. One game, in 2010, included Russia’s Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu.

That year Mishustin was named Russia’s tax chief, stepping into his mentor’s shoes. With several years in finance under his belt, he was counted as one of the top three richest Russian officials.

Over the following decade, Mishustin won plaudits for his transformation of Russia’s tax system. Last year, the Financial Times published a glowing review of his work with the headline: “Russia’s role in producing the taxman of the future.”

Mishustin also started to fashion himself after a Putin-era Russian official by aligning himself with the Orthodox Church. In recent years he has gotten involved with his own local branch in the Moscow suburbs, where many members of Russia’s business and political establishments are based. Last week, BBC Russian reported that, in 2017, the church presented Mishustin with the Patriarchal medal for church construction.

BBC Russian also reported, however, that the money for the work was donated in his sister’s name — and that she owns up to 1 billion rubles ($16.1 million) in real estate. Critics like opposition leader Alexei Navalny have seized on what they have taken to be hidden wealth, as they say is the case with many Putin officials.

Some of Mishustin’s early moves as prime minister have also riled Russian liberals.

Last week, he ordered that salaries of police officers in Moscow and St. Petersburg who maintain order during street protests should be doubled.

“Effective manager, updated government?” Navalny ally Lyubov Sobol wrote on Twitter. “Actually just the same thievery, that hates its own people and despises laws.”

Long live Putinism?

In interviews with The Moscow Times, members of Russia’s IT and business communities welcomed Mishustin’s appointment. Pointing to his stance in the ’90s and early aughts, as well as his work as tax chief reforming an inefficient system, they hope he can do the same with a bigger platform.

The Mishustin of the ’90s may no longer exist, however, as his career arc has in some ways hewed to Russia’s development since the fall of the Soviet Union. If the zeitgeist of that time was an openness to the West, Mishustin might only have embodied that spirit as it was the status quo.

“He didn’t have an internal doctrine to speak of,” Ilya Ponamoryov, an entrepreneur turned exiled former opposition State Duma deputy, who was a member of GP Club, said by phone from Kiev.

And as Russia has grown increasingly isolationist, even developing a so-called “sovereign internet” that could cut its networks off from the rest of the world, observers may very well wonder what the prime minister, who has not laid out his political views since his appointment, now believes.

A clue could lie in what a former colleague at UFG, who asked not to be named, underscored: that Mishustin is a “systems engineer in all senses of the phrase.”

“Everything else about him is derived from this: He understands systems and how to work in them,” the former colleague said.

For now, Mishustin’s main mandate will be to spur Russia’s sputtering economy. Described by former colleagues in interviews with The Moscow Times as a “tough guy” who can be a strict manager when needed, a government source recently told the Financial Times that Mishustin has already axed unwanted officials from the previous government without even giving them time to collect their belongings.

That toughness has left old acquaintances curious as to how Mishustin will approach his new role.

“One the one hand, he’s very loyal,” said Elkin. “On the other hand, he’s not a lapdog. It’s an interesting contradiction.”