When John Gartner, a former Rhodesian soldier who now heads the military security company OAM, was approached by a Mozambican official to help fight the Islamist insurgency in the country’s north, he thought he was about to win a lucrative contract.

“We presented them with a first-class proposal in early August. We have so much experience in operating in Mozambique and know the tough environment very well. Trust me, we would have done an excellent job,” he told The Moscow Times.

Dolf Dorfling, an ex-colonel in the South African army and founder of the Black Hawk private military contractor, likewise submitted a “strong” proposal for a country he knows “like the palm of his hand.”

They both lost out to a new player in town — the Kremlin-linked Wagner Group, believed to be owned by Yevgeny Prigozhin, a businessman with close links to Russian President Vladimir Putin often referred to as “Putin’s Chef” because of his catering business.

While the veteran mercenaries admitted they couldn’t match Wagner’s low costs and high-level political connections, they cast doubt on the Russian company’s ability to operate in Mozambique because they say it knows neither the terrain nor the politics.

“Look, it’s money and politics, it was clear we couldn’t compete with Wagner,” said Gartner, “But now they are in trouble there, they are out of their depth.”

In September, about 200 Russian Wagner mercenaries arrived in Mozambique’s capital Maputo, news first reported by The Times of London and independently confirmed by The Moscow Times.

Since arriving, they have been engaged in a fierce fight with an Islamic State-linked insurgency in the country’s gas-rich, Muslim-majority Cabo Delgado region, which has claimed over 200 deaths since 2017.

Black Hawk and OAM are two of the many private military contractors operating in Sub-Saharan Africa. Their rise has been linked to the end of apartheid in South Africa, which released many skilled soldiers eager to be paid to help African governments struggling to curtail internal rebellions. Many are now aged between 55 and 65, but say they have the knowledge and experience to keep working in Africa.

Gartner said he had proposed to bring around 50 highly qualified experts to Mozambique at a cost of between $15,000 and $25,000 per person per month.

While no public information is available on how much Wagner pays its mercenaries, Yevgeny Shabayev, a former Russian military officer and self-appointed spokesman for the group, told The Moscow Times that on average, a lower-rank Wagner soldier receives between 120,000 and 300,000 rubles per month ($1,800 – $4,700).

Perhaps more important, the military contractors said, is the political backing Wagner has attracted compared to traditional mercenary groups.

Prigozhin is emerging as a key figure in Russia’s increasingly expansive foreign policy in Africa, and Wagner troops have been reported operating in Sudan, the Central African Republic and Libya.

Last week, The New York Times reported that following a meeting in Moscow between Putin, Prigozhin and Madagascar’s then-president Hery Rajaonarimampianina, Russian operatives were sent to the country with the aim of influencing the local elections. Their security was reportedly provided by mercenaries from Wagner.

Mark Galeotti, an expert on Russian security affairs, says that Wagner’s unique blend of proximity to the Kremlin and low costs make it attractive.

“They are cheap and come as part of a package of regime-support services, including political technologies.”

Mozambican President Filipe Nyusi flew to Russia and met Putin at the end of August — two months before the country’s October presidential elections — where he signed a number of energy and security agreements.

While there is no evidence to suggest Russia sent operatives to influence the Mozambican elections, companies linked to Prigozhin have been accused of propping up Nyusi and his party.

In the run-up to the elections, a think tank called Afric conducted a poll that predicted victory for Nyusi. As the publication of election polls is illegal during the campaign period in Mozambique, its founder Jose Matemulane published it on the International Anticrisis Center website, a Russian NGO linked to Prigozhin. The poll ended up being widely shared across social media in Mozambique.

Afric’s page was eventually suspended by Facebook at the end of October after Nathaniel Gleicher, Facebook’s head of cybersecurity policy, said the entity was associated with Prigozhin and had attempted to interfere in the domestic politics of African countries.

The U.S.-based Stanford Internet Observatory research center also identified four separate Prigozhin-linked Facebook pages created on Sept. 23, 2019, which frequently posted identical content. They lauded the government’s success in fighting the Islamist insurgency in Cabo Delgado and criticized the main opposition party Renamo.

In over their heads

A few weeks after Wagner’s arrival in September, reports started coming out of Mozambique that the group’s mercenaries were being ambushed, killed and beheaded in Cabo Delgado.

Two Mozambique army sources told The Moscow Times in October that at least seven Russians had been killed by the insurgency that month. Over a dozen independent analysts, mercenaries and security experts working in the region have since told The Moscow Times that Wagner is struggling.

“You have to realize this is one of the toughest environments in the world,” said Al Venter, a veteran South Africa journalist who has written extensively about mercenaries on the continent.

“The consensus is that Wagner has almost no experience of the kind of primitive bush warfare being waged in there. They are going to come very badly unstuck,” he added.

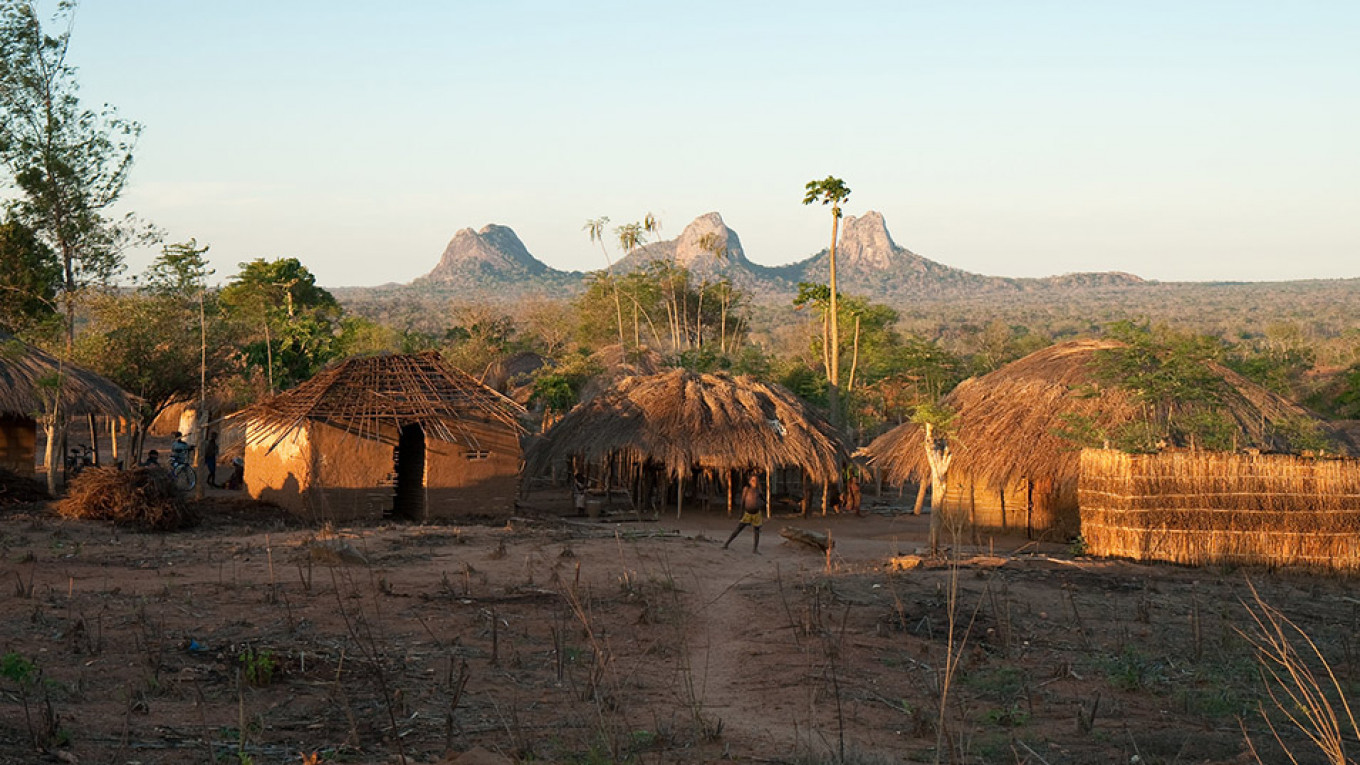

Cabo Delgado is one of the poorest and least developed areas in the region. It has limited basic infrastructure, including a lack of roads and hospitals, that makes it an environment that is “ideal” for ambushes, according to a Mozambican intelligence specialist based in the area who wished to remain anonymous.

“The undergrowth is so thick there that all the high-tech equipment Wagner brought ceases to be effective. The Russians arrived with drones, but they can’t actually use them,” the specialist said.

The environment is not the only problem Wagner faces.

Two sources in the Mozambique military, also speaking under condition of anonymity, described growing tensions between Wagner and the Mozambique Defense Armed Forces (FADM) after a number of failed military operations.

“We have almost stopped patrolling together,” one of the two soldiers said.

Jasmine Opperman, a terrorism expert based in South Africa, believes “a perfect storm” has formed around Wagner in Mozambique.

“The Russians don’t understand the local culture, don’t trust the soldiers and have to fight in horrible conditions against an enemy that is gaining more and more momentum. They are in over their heads.”

Growing pains

Wagner’s problems in Mozambique raise bigger questions about the company’s rapid growth, according to Galeotti.

“They have clearly had to expand since their early Syrian days and also have to make a profit. This means being less picky with recruits. They are increasingly operating in theaters where they don’t have much expertise.”

Shabayev, who says he is in regular contact with Wagner soldiers, echoed these sentiments. He expects the death toll for Wagner soldiers to rise across the world in coming years, but said it will be hard to glean concrete information given Wagner’s secrecy.

He said the first bodies of Wagner soldiers who died in Mozambique have already arrived in Vladimir, a region outside Moscow, where families have been given hefty compensation in return for silence.

The Moscow Times was unable to independently confirm this.

For now, Gartner and Dorfling are on standby, monitoring developments in Mozambique closely.

“Once Mozambique realizes that Wagner won’t be able to do the job alone, we will be back in demand,” said Dorfling.

Sources told them that Wagner has started to look around for local military expertise, although they haven’t heard anything yet.

“If you could let Wagner know we are available to help, that would be great. We would like to come in and do what we do best,” said Gartner, before hanging up.

Islamic State is a terrorist organization banned in Russia.