Voronezh wasn’t cutting it.

Artyom had been out of college for four years, and job openings in the southern Russian city were sparse. Last fall, in search of better employment opportunities, he headed north to St. Petersburg.

But the journey wasn’t cheap. “I needed money for the move, an apartment and for daily expenses before I found work,” says Artyom, who asked to be identified by his first name only.

So Artyom opened a credit card account to finance the move. Three months later, the 26-year-old is already struggling to pay off the card’s 24 percent interest rate. While his mechanical engineering degree helped him land part-time work fixing household appliances, the inconsistent gigs don’t bring in enough earnings and the debts are beginning to pile up. Now he’s looking for a new loan to pay off the card.

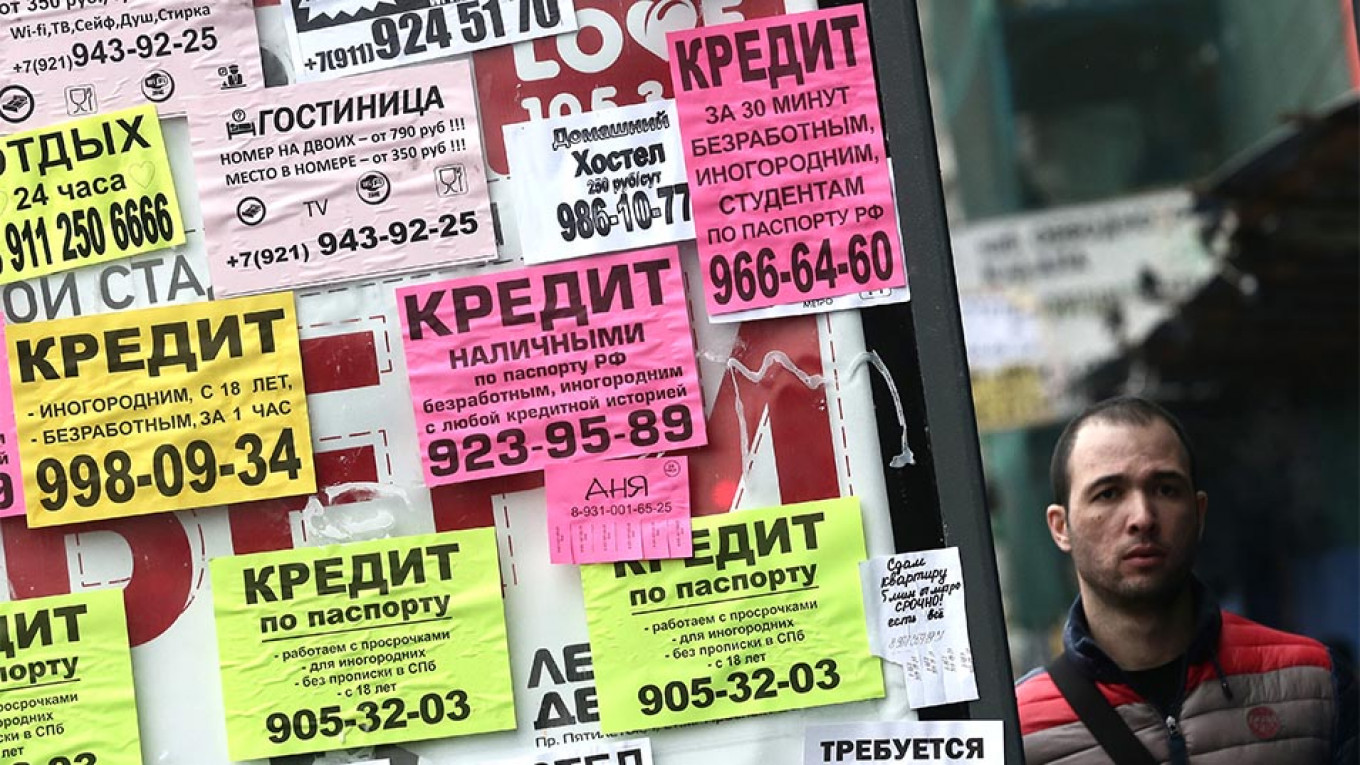

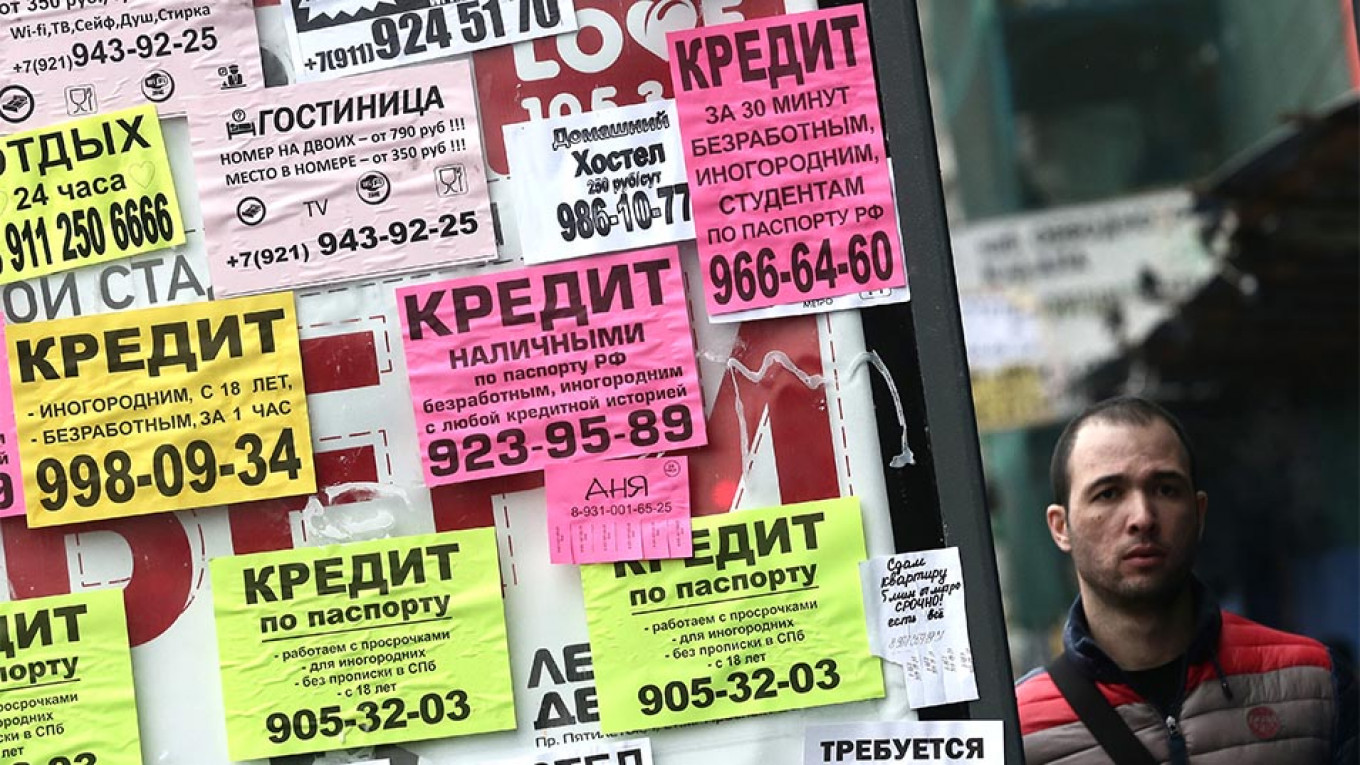

Artyom’s situation isn’t unique. Last year, according to the Moscow-based United Credit Bureau (OKB), personal loans grew by 46 percent compared to 2017, amounting to 8.6 trillion rubles ($130 billion). Many were hoping to refinance existing debts: the number that approached St. Petersburg’s Credit Bureau No. 1 to do so doubled in 2018, a company spokesperson told The Moscow Times.

In an effort to boost a stalling economic recovery, Russia’s central bank lowered interest rates to promote cheaper lending. For the many Russians whose incomes were stagnating, leaving them struggling to cover their daily expenses, turning to the banks proved attractive.

“This behavior is quite rational,” says Dmitry Polevoi, chief economist of the Russian Direct Investment Fund. “At the same time, the debt burden has reached a record high, totaling 26 percent of the population’s annual income.”

Looking up

In the wake of the 1998 financial crisis, Russians began signing up for credit en masse in the mid-2000s, once the country’s oil boom was in full swing. “There was a steady increase in purchasing potential combined with a sharp growth in inequality,” says Grigory Yudin, an economic sociologist at the Higher School of Economics. “A big slice of the Russian population was looking upward and felt that they, too, had a moral right to this wealth.”

That reason was why Artur Fagdeyev began opening credit card accounts in 2010. “I figured that I’d be able to lead a better lifestyle,” he says. And for nearly a decade, the 42-year-old electrician didn’t mind that he had become saddled with debt.

Then he and his wife had a baby, and Fagdeyev decided it was time to turn things around. He took out a loan last year at a better rate to pay off his cards, which carried interest rates of 29.9 percent. But the interest rate on the new loan was so much lower — 15 percent — that the Leningrad region resident figured he could use another, telling himself that he would only use the funds for necessities.

“I hadn’t had the money to get a new car in a long time,” Fagdeyev says. “And I need a good one because I’m often driving around small villages with horrible roads because of my work.”

But he didn’t stop there. He soon took out yet another loan — and this time, he didn’t follow his new principles. “I used it to build myself a banya,” he says sheepishly, referring to a Russian bathhouse.

St. Petersburg’s Credit Bureau No. 1 says it has seen a spike in customers hoping to refinance previous loans. Denis Vyshinsky / TASS

St. Petersburg’s Credit Bureau No. 1 says it has seen a spike in customers hoping to refinance previous loans. Denis Vyshinsky / TASSYudin explains such spending behavior by pointing to the “demonstrative” spending of Russia’s rich. “They buy castles, houses here and there, yachts, wineries, expensive fur coats,” he says. “Of course, most Russians can’t afford this, but they want to show off something, too.”

Following Western-imposed sanctions resulting from Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea from Ukraine, however, Russians’ spending decreased as the country’s economy stagnated. At the same time, inequality kept growing, Yudin says. (According to a 2018 report by Credit Suisse, Russia is the most unequal of the world’s major economies, with 89 percent of the country’s wealth owned by its richest 10 percent.) “The motivation to borrow money didn’t go away,” he says.

Indeed, in addition to refinancing previous debt, last year’s lowered interest rates gave consumers a window to buy what they could not afford during the previous four years, economists say. According to an OKB spokesperson, cash advances (50 percent) and credit cards (63 percent) saw the largest growth last year.

“People borrow money for different reasons,” says Roman Korotayev, director of the legal firm “Revers” in the Urals city of Berezniki. “For houses, for cars, for their businesses. But many people also use it on stupid things like iPhones or fur coats or vacations or what have you.” (Last fall, a BBC Russian Service article described the trend of Russians going into debt for showy weddings.)

And the segment of the Russian population that is taking on the bulk of such loans, Yudin notes, is by far the poorest. “You’ll find families that are using 50 percent of their income to pay off credit,” he says. “And without stable jobs, this can turn into a catastrophe for them.”

Bottoming out

The bulk of Korotayev’s clients find themselves in such situations, turning to him to declare bankruptcy often after having taken on one too many lines of credit. Unexpected life changes like a job loss or a spouse’s death can begin a vicious cycle of debt, Korotayev says.

Unsurprisingly, then, last year’s spike in personal loans coincided with a spike in declarations of bankruptcy. Yulia Kombarova, general director of the St. Petersburg-based Legal Bureau No. 1, says the firm saw a 30-percent increase in bankruptcy claims in 2018.

One of the main reasons, Kombarova says, is that while Russians, like Americans, rely heavily on loans, Russia’s lending system presents much greater risks.

“These loans come at a much higher interest rate of 20 to 30 percent,” she says. “With an unstable economic situation, long-term planning is much more difficult. Usually our clients lived on credit for many years with a good credit history until it all came undone.”

Alexei (last name withheld), 47, was one such client. The St. Petersburg resident took out his first loan for his small construction business in 2004. “It worked out for me for many years,” he says.

But the business was unstable. Workers came and went; fighting for his piece of the pie with behemoth construction companies proved difficult; and clients didn’t always pay up on time. In 2016, it all came tumbling down. “Now I’m starting from a blank slate,” Alexei says.

While he doesn’t regret having taken loans, he says he “categorically” no longer wants to.

“Luckily because I’m an engineer by training I should always be able to find work,” he says. “I feel fine walking places instead of driving until I can save up to buy a car. And I’m more patient now. It feels better to not have it all hanging over me anymore.”