Azerbaijan’s military success confirmed by a Russian-brokered ceasefire has rapidly changed the map of the South Caucasus. Attention has now turned to the rich cultural heritage, in particular the Armenian churches falling under Azerbaijani control.

Beyond preserving these precious monuments for future generations and as places of worship, this is a test of goodwill. Armenia and Azerbaijan have agreed to a cessation of hostilities but are still a long way from peace. On an issue where human lives are not at stake, can the parties agree to a more inclusive narrative of regional history that does not seek to erase the identity of the other? The early signs are not positive.

This is not a simple story. As Azerbaijani armed forces recaptured territories this autumn that had been under Armenian occupation since 1993, the scale of cultural devastation became apparent. Armenians had not just destroyed almost all the houses, but also, in many cases, wrecked graveyards. Pictures of a mosque in Alkhanli village of Fizuli region, which had been turned into a cowshed, caused outrage.

The Azerbaijani culture ministry also expressed indignation at Armenian excavations at the famous Azykh cave, a prehistoric site in the Martuni region which was extensively researched in the Soviet period, and at alterations to the Shahbulaq fortress in Aghdam region.

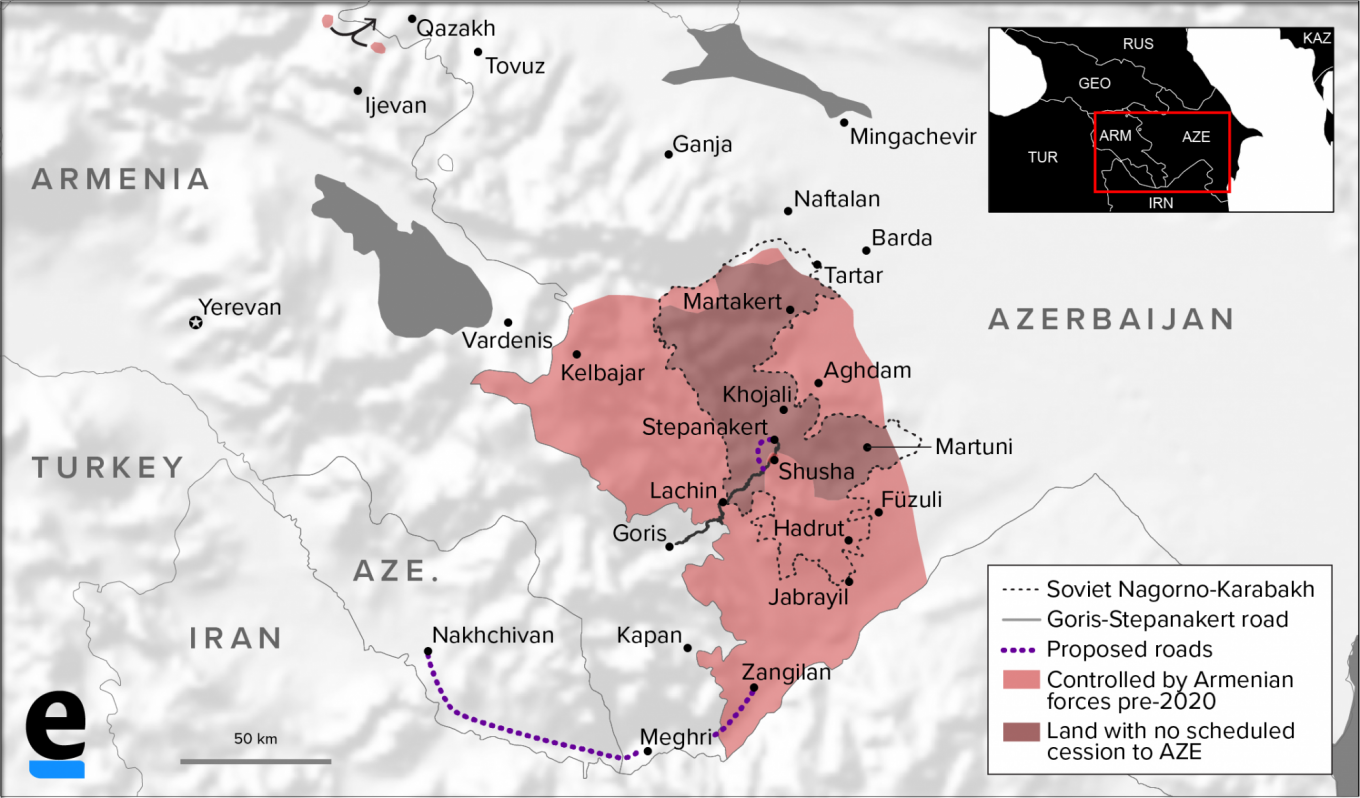

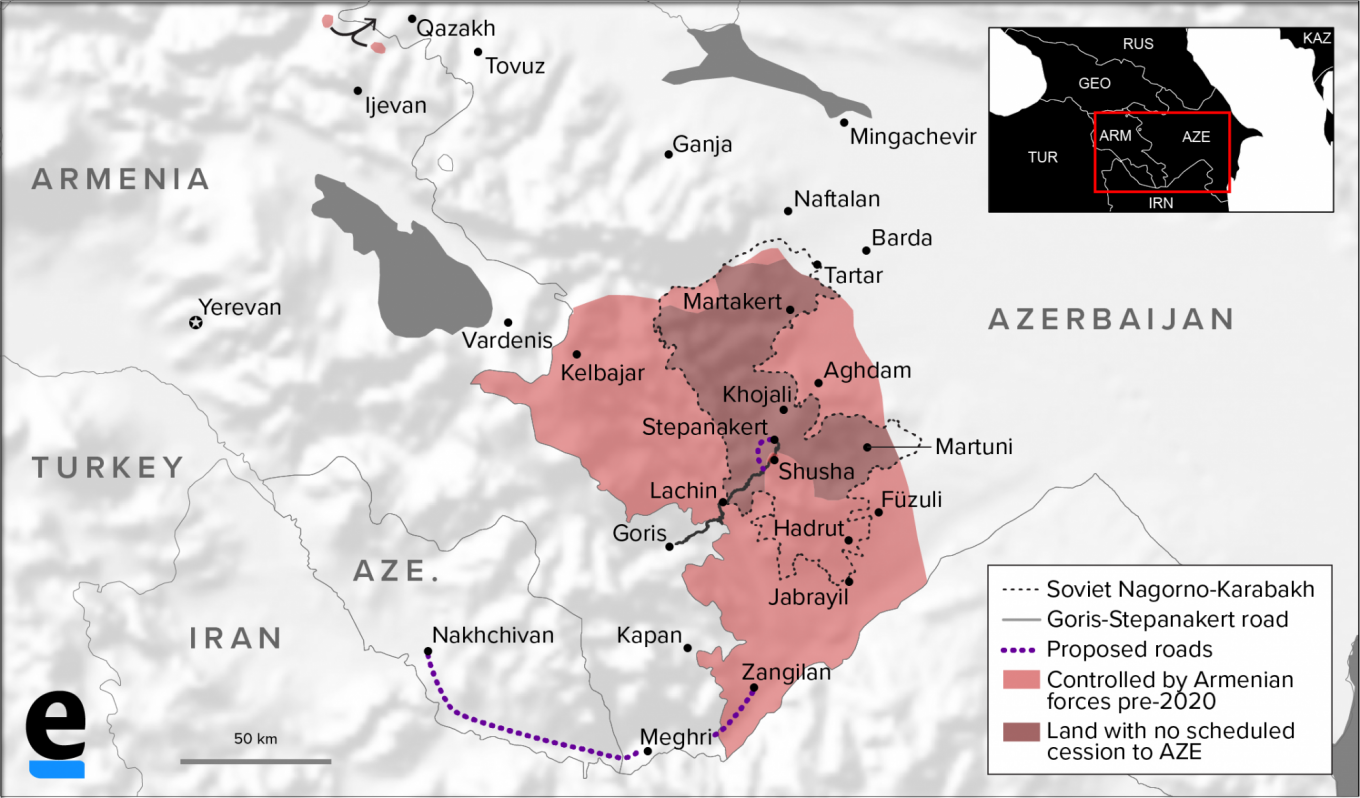

As Azerbaijani forces moved deeper into Karabakh, the issue then arose of the hundreds of Armenian churches, tombstones and monuments there. Azerbaijan now controls most of Hadrut region and its monuments such as the Gtichavank church, which dates back to the 13th century.

As Armenians prepare to cede Azerbaijani territories under the Nov. 10 deal, they are handing over many significant monuments. These include the Tsitsernavank basilica church in Lachin region and the archaeological site of the old city of Tigranakert in Aghdam region. The Amaras monastery in Martuni region, which contains a 5th century mausoleum and is said to date back to the era of St. Gregory the Illuminator, the founder of the Armenian church, is situated on the new front line and it is not clear whether Armenians or Azerbaijanis currently control it.

Most attention has focused on the 12th century Dadivank monastery in Kelbajar region, now due to be returned to Azerbaijan on Nov. 25. News footage showed Russian peacekeepers at the site.

Azerbaijan’s culture ministry has said it regards churches such as Dadivank to be “Albanian,” not Armenian. Anar Karimov, first deputy culture minister of Azerbaijan, posted a controversial tweet in which he referred to the monastery as having been “built by wife of Albanian prince Vakhtang.”

The “Albanian” reference is to a bitter political-historical quarrel that has raged in parallel to the military Karabakh conflict.

The idea that churches in Karabakh are not Armenian but actually “Caucasian Albanian” stems from a 1960s Soviet Azerbaijani thesis advanced by Ziya Buniatov, an influential scholar who was later regarded as Azerbaijan’s national historian.

The Albanians were a small Christian people in the Caucasus region who had mostly died out by the 10th century — although the Udins, a small ethnic group in northern Azerbaijan, are their likely successors. A handful of old fragments of Albanian script have survived and been deciphered.

However, Buniatov and others argued that a Christian ecclesiastical eparchy named the “Church of Albania” had lasted until the 19th century and that this was proof of a separate Albanian identity lasting hundreds of years longer than previously thought. This ambiguity allowed Azerbaijani politicians to assert that Karabakh’s churches were not actually Armenian (and its people were therefore not either) — while ignoring the fact that they were built in an Armenian style and covered in Armenian-language inscriptions.

What will happen to Karabakh’s Christian monuments now? Judging on past experience, their future may be one of preservation, unilateral restoration or destruction.

Destruction has been the fate of almost all Armenian monuments in Azerbaijan’s exclave of Nakhchivan. The most egregious case was the razing of the famous medieval Armenian cemetery at Djulfa, with thousands of khachkar cross-stones, in Nakhchivan in 2005-06. As Nakhchivan is relatively unvisited, this story has not received the attention it would if the region were more accessible.

Unilateral and tendentious restoration has been visited on several monuments on both sides of the conflict.

For example, Armenians have restored and re-opened a “Blue Mosque” in Yerevan, a city which had a strong Muslim identity in the 18th and 19th centuries. The mosque is mostly used for worship by resident or visiting Iranians. A smaller less conspicuous mosque in Yerevan situated at Vardanants Street near the city center was pulled down as the Karabakh conflict began.

The Karabakh Armenian authorities also controversially restored the two mosques in the town of Shusha. The Yerevan and Shusha restorations used the mirror image of the “Albanian theory.” Armenian restorers called the mosques “Iranian” or “Persian,” seeking to deny any Azerbaijani identity to them — even though it is clear that the Turkic-speaking Shiite builders of these mosques were the ancestors of modern-day Azerbaijanis.

Similarly, the Azerbaijani authorities have restored the Armenian church in the center of Baku. However they have not put a cross on the dome, and the only public service in the church in the last 30 years occurred when Catholicos Karekin visited Baku in 2010. A smaller 18th century church of the Virgin Mary near Baku’s Maiden Tower was pulled down in 1992. In 2008 many graves in the Christian cemetery in the north part of Baku, known as Montino (the main Armenian cemetery in the city), were also hastily razed to make way for a new road.

The Azerbaijani authorities have also restored churches in the towns of Nij and Gabala in controversial fashion. The Nij church — which has good reason to be called “Albanian” as it is located in a region populated by the Udin ethnic group — was restored with the support of a Norwegian NGO, Norwegian Humanitarian Enterprise. However, Armenian-language inscriptions on the church were erased at the end of December 2004, with the result that foreign ambassadors declined to attend the re-opening of the church.

Based on that experience, Steinar Gil, Norwegian ambassador to Azerbaijan at that time, commented, “I am worried because Azerbaijan has a sad reputation related to Armenian religious monuments,” and referred to “the almost total Albanization of Armenian churches and monasteries, irrespective of their time of construction.”

As members of UNESCO, Armenia and Azerbaijan are both obliged to honor international cultural conventions, including the 1954 Hague Convention which is designed to protect monuments at risk due to armed conflict. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov also invoked UNESCO in comments on Nov. 12. But UNESCO mainly operates in a country at the discretion of a national government. So pressure to preserve monuments may come down to mobilization by international heritage experts.

Well-known monuments may remain untouched after the intervention of no less an authority than Russian President Vladimir Putin, who personally asked President Ilham Aliyev for — and reportedly received — reassurances on the “preservation and normal operation” of churches such as Dadivank.

Simon Maghakyan, an Armenian scholar who researched the Djulfa cemetery destruction, says he is more worried about the fate of lesser-known Armenian monuments. He said, “My fear is that the monuments at the highest risk for immediate erasure are being overlooked, including smaller medieval churches and especially the numerous statuesque khachkars that are nearly impossible to ‘Albanize,’ given their rich Armenian inscriptions. One of the most prominent khachkars at grave risk is the 14th century Angels and the Cross in the Vank village of Hadrut region, which Azerbaijan captured last month.”

Those Armenian and Azerbaijani experts who work to an international standard rather than a nationalist agenda can play a positive role — but only if given the space to do so. Azerbaijani scholar Cavid Aga argues, “By preserving Armenian heritage, we can learn Caucasian Albanian heritage too.”

This article was first published by Eurasianet.