When anti-government protests erupted on Russia’s side of the Caucasus Mountains in October, authorities did something they’d never done before: cut mobile internet service to an entire geographical area.

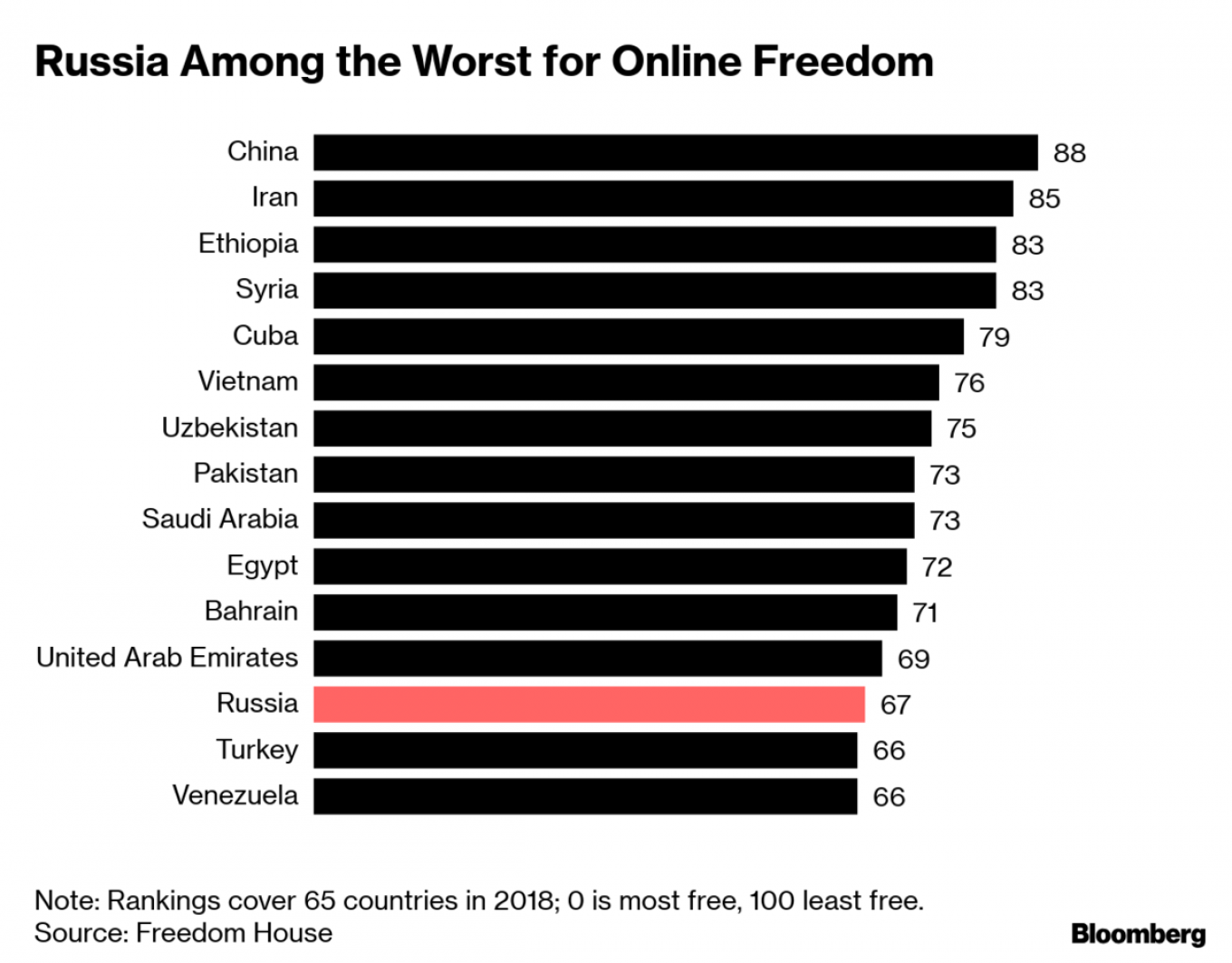

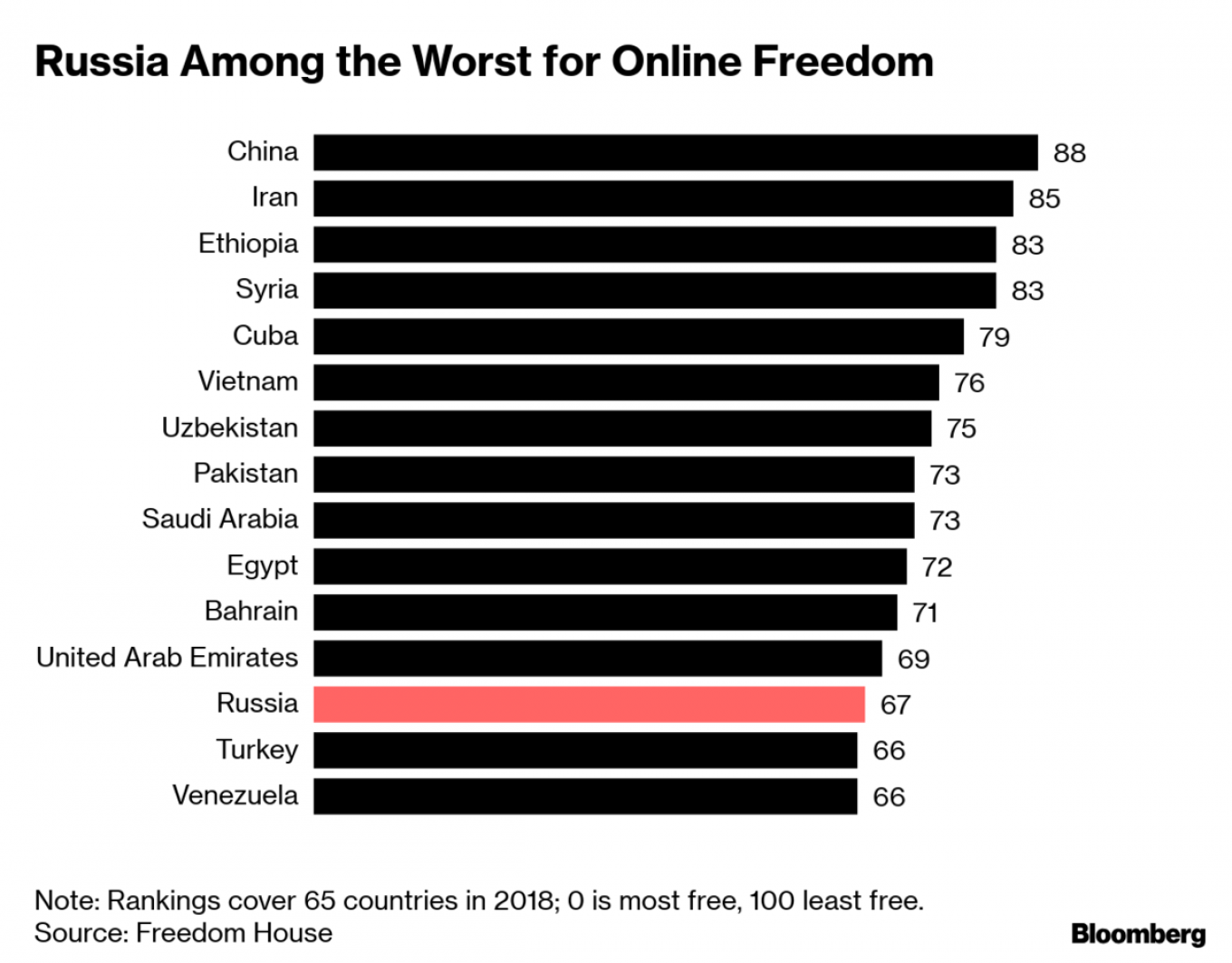

For almost two weeks, tens of thousands of mainly Muslim Russians were prevented from accessing social media sites and sharing videos through their smartphones. Unlike China, where control of the internet is uniquely centralized, Russia doesn’t yet have an easy way to quarantine negative news, so it had to force commercial carriers to curtail local services one by one.

Russia’s censorship deficit relative to China is about to narrow. Backed by President Vladimir Putin, lawmakers in Moscow are pushing a bill through parliament dubbed “Sovereign Internet” that’s designed to create a single command post from which authorities can manage and, if needed, halt information flows across Russian cyberspace.

Putin is touting the initiative as a defensive response to the Trump Administration’s new cyber strategy, which permits offensive measures against Russia and other designated adversaries. But industry insiders, security experts and even senior officials say political upheaval is the bigger concern.

“This law isn’t about foreign threats, or banning Facebook and Google, which Russia can already do legally,” said Andrei Soldatov, author of “The Red Web: The Kremlin’s Wars on the Internet” and co-founder of Agentura.ru, a site that tracks the security services. “It’s about being able to cut off certain types of traffic in certain areas during times of civil unrest.”

Tensions may have subsided along Russia’s southern border in the last four months, but they’re ticking up across the country. Since winning re-election by a landslide last March, Putin’s approval ratings have sunk to multiple-year lows, dragged down by decisions to cut spending and raise taxes while wages continue to slide and consumer prices creep ever higher.

The draft law, which was co-authored by Andrei Lugovoi, the KGB veteran who’s wanted in Britain for the 2006 murder of renegade agent Alexander Litvinenko, is actually a hodgepodge of bills, some of which have been in the works for years. The ultimate goal, according to Putin, is to ensure that the Runet, as the domestic internet is known, continues to function in the event the U.S. tries to isolate its former Cold War foe digitally.

“They sit there, it’s their invention, and everyone listens, sees and reads what you say”

Bloomberg

BloombergPutin told media executives inside the Kremlin last month that he doubted the U.S. would unplug Russia from the web because “it would cause them enormous damage.” Still, he said the threat is real so Russia has to prepare.“They sit there, it’s their invention, and everyone listens, sees and reads what you say,” Putin said. “The more sovereignty we have, including in the digital field, the better. This is a very important area.”

The first step toward the kind of independence envisioned in the legislation is the establishment of the “technical means of countering threats.” This refers to installing special boxes with tracking software at the thousands of exchange points that link Russia to the wider web.

The units would feed a single nerve center, allowing regulators to analyze both the volumes and kinds of traffic in real time and selectively block or reroute certain types of flows, be they YouTube videos or Facebook feeds. So-called deep-packet inspection, or DPI, has been a popular tool for operators of large networks for years because it helps optimize user loads.

Content providers use the technology to harvest the increasingly valuable metadata about consumers that they sell to advertisers, but DPI is also a “powerful mechanism” for repression, according to former Google chief Eric Schmidt. Not only can DPI censor “objectionable activities,” it can also slow the internet “for target users or communities,” Schmidt wrote in 2014.

Lugovoi, the co-sponsor of the bill, said in hearings that officials have “absolutely no clue about the communications networks laid in Russia and cross-border connections—who owns them, how they’re used, what kind of information is sent.” Once the monitoring hub is set up, he said, “we’ll be able to see all this online.”

The BBC caused an uproar on social media in Russia last month when it reported that authorities in Moscow were planning to isolate the Runet completely for a few hours this spring to test the system. But that’s neither true nor technically possible, according to officials and industry executives who’ve been briefed on the project.

Internet providers and wireless carriers are objecting to the bill as written on several grounds, not least of which is expense. They say that while the government has pledged to pay the costs of implementation, the 20 billion-ruble ($304 million) estimate put forward by one of the authors won’t be enough for procurement, installation and refinement, let alone maintenance.

But even before getting to that point, officials need to involve market participants in extensive tests of all relevant hardware and software to avoid “major disruptions” that could cost companies tens of billions of rubles in lost revenue, the industry’s main lobby group said in a statement.

Rongbin Han, a professor of international affairs at the University of Georgia in the U.S. who studies the Great Firewall of China, said all major countries are extending their sovereignty into cyberspace for one very good reason—new threats are emerging all the time.

“Russia is moving in a similar direction as China,” Han said. “You don’t necessarily need to shut down the entire internet to quash political dissent. It’s smarter just to filter online content.”

One Russian official said the new law will make it easier for authorities to monitor and disrupt scores of apps and message groups that are currently classified as illegal. He said as many as 30 million Russians use such services, the most popular of which is Telegram, a platform founded by rebellious tech entrepreneur Pavel Durov and his mathematician brother.

Russian efforts to force Durov, who’s based in Dubai, to hand over his encryption keys last April resulted in protests and mass ridicule. Authorities tried to pull the plug on Telegram in Russia, but ended up bringing down hundreds of unrelated sites in the process, including retailers, banks and airline-ticketing systems.

“Putting monitoring boxes on every node may slow down not only the Runet, but the global internet”

The Runet went largely unregulated in the early years of the Putin era as the Kremlin focused on bringing to heel the most influential media outlets of the time, which were in broadcasting and print. But censorship has been systematically tightened, particularly since nationwide protests erupted in late 2011, when then-premier Putin announced his return to the presidencyRussia now censors a variety of topics online, often under the pretext of rooting out “extremism.” It also blocks foreign companies like LinkedIn and Zello that refuse to locate servers inside the country. In total, about 80,000 sites are currently blacklisted, according to Roskomsvoboda, a Moscow-based group that campaigns against online restrictions.

Artem Kozlyuk, the group’s founder, said if Russia is truly afraid of getting kicked off the web by the U.S. then it’s playing into America’s hands by trying to centralize a distributed system. That would both make the Runet easier to attack and increase the likelihood of some unskilled official crimping connection speeds around the world by mistake, he said.

“Russia is one of the world’s largest hubs for exchanging of traffic, with fast channels,” Kozlyuk said. “Putting monitoring boxes on every node may slow down not only the Runet, but the global internet. It’s like closing your airspace.”