Russia came under siege from climate change in 2020, and experts warn that Arctic heatwaves, fires and melting permafrost could be worse this year.

The year began with the warmest winter in 140 years of recorded meteorological data, leaving Moscow — a city usually covered in snow for four months of the year — entirely snow free for the month of February.

In the summer, Siberia suffered its worst ever forest fires, which had burnt through an abnormally warm winter to emit in three months roughly as much carbon as Egypt does in a year.

In the fall, a toxic algae bloom that some scientists linked to climate change wiped out 95% of marine life along a section of the Kamchatka coastline.

In Vladivostok, a freak frozen rainstorm left tens of thousands without electricity or heating for days, as icy gales downed power lines and damaged buildings. Elsewhere, the melting of Arctic permafrost and drought on the southern Russian steppes continue to have unpredictable consequences for fragile ecosystems and livelihoods.

Even so, climate change and the environment remains a niche concern for most Russians: a September survey by the Levada Institute pollster saw only 22% of Russians single out environmental issues as a principal concern.

Asked by The Moscow Times about the environmental challenges that await Russia in the year ahead, Russian climate scientists, experts and activists stressed that present trends will continue. They warned that in 2021, the world’s largest country will face an accelerating climate crisis as warming weather sparks more environmental disasters with ever more damaging consequences for ordinary people.

‘The trend is clear’

Though climate scientists stress that their discipline is unable to make meteorological predictions with any degree of certainty, all are clear that the trend line for Russia is bleak.

“It is impossible to make any concrete predictions about the year ahead,” said Alexander Kislov, a professor of climatology at Moscow State University.

“However, the trend is clear: Each five year period is warmer than the last, and Russia is warming faster than almost any other country.”

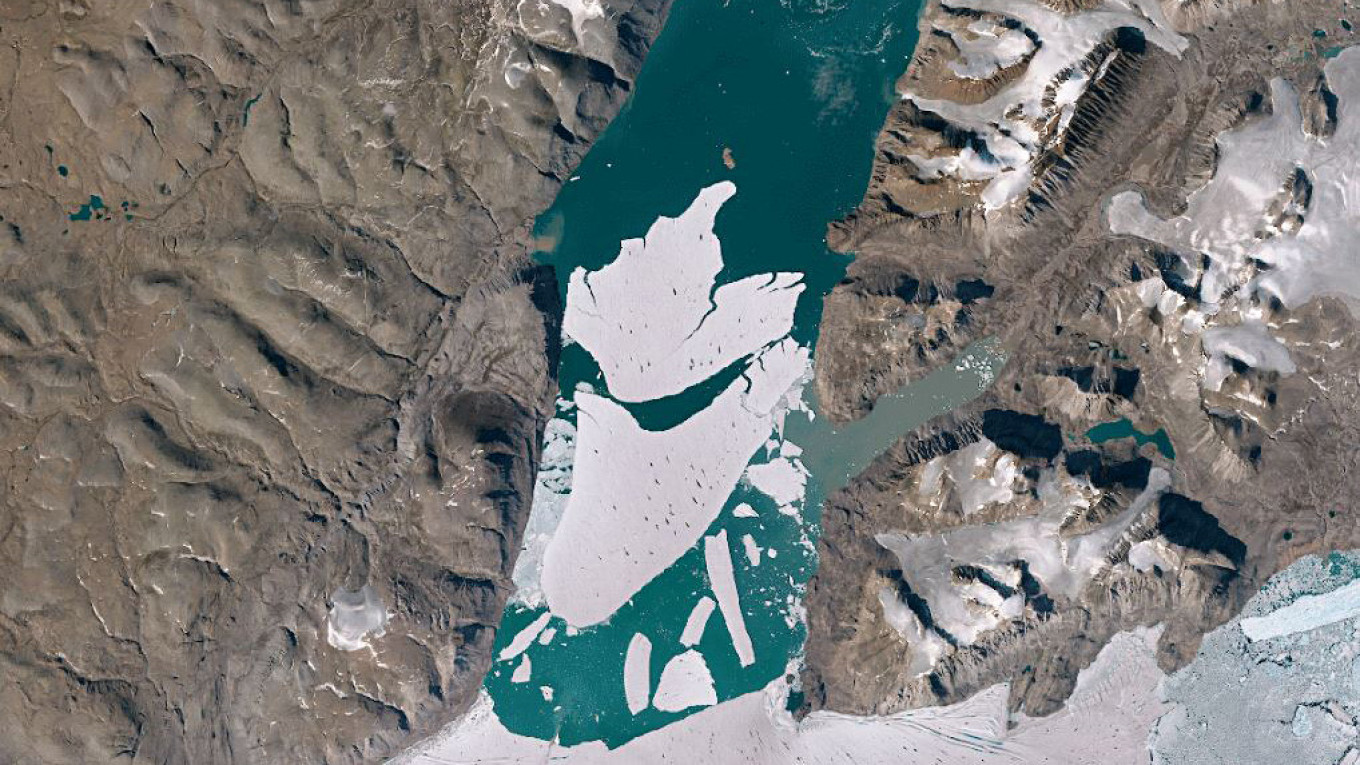

With temperatures in Russia rising at around two-and-a-half times the pace of the rest of the planet, in much of the Arctic north average temperature rises have already exceeded the 2 degrees centigrade increase the Paris Climate Agreement aims to prevent worldwide.

According to Kislov, Russia’s continental and subarctic geography means that while year-to-year trends may vary, environmental disasters and warm, snowless winters will become the country’s new normal.

“We cannot rule out the possibility that 2020, its catastrophes and record-breaking temperatures were an anomaly, and that 2021 will represent a return to the norm. However, it is also entirely possible that it was not an anomaly.”

For some scientists, a new and unsettling unpredictability is the essence of a rapidly changing climate, as spiking temperatures wreak unexpected havoc on the environment.

“In our country, we are already living in a time when forecasts have become so difficult that they should be kept strictly to oneself,” said Roman Desyatkin, a climate scientist from Yakutia, a Siberian region 90% covered in rapidly melting permafrost.

However, Desyatkin was willing to make one definite prediction. With winter 2020 shaping up to be another unusually warm one for Yakutia, the pace of permafrost melt — which has already exposed deadly buried pathogens, released trapped methane and doomed buildings to slow collapse — will be “even more intense” next year.

More disasters

For some in Russia’s environmental community, 2021 is likely to see climate change having an increasingly direct impact on people’s lives.

“Russia has always suffered natural disasters, but we have so far been lucky that they’ve not tended to impact very many people. That will change.” said Roman Pukalov, director of environmental programmes at the Moscow-based NGO Green Patrol.

“Each year there will be more disasters, with more direct effects on people. I wouldn’t be surprised to see forest fires or floods — which have tended to affect remote, sparsely populated areas — affecting major population centres in future.”

With climate change-related disasters, from forest fires to glacial collapses, disproportionately affecting regions geographically removed from Moscow, some believe the urgency of adaptation to climate change could become a wedge issue, exacerbating the sometimes testy relationship between Russia’s capital and its provinces.

“In 2021, we’ll see a lot more forest fires and permafrost melt,” said Arshak Makhichyan, a 26-year old climate activist who has staged a one-man climate protest every Friday for over a year on Moscow’s Pushkin square.

“But since it will all likely happen a long way from Moscow, it’s hard as an activist to feel optimistic. There’s a lot of energy among climate activists, but how do you make climate a central issue in the big cities, where most people live, but where it’s not felt so strongly?”

Ultimately, however, predictions for Russia’s in 2021 come down to the uncertainties created by an unpredictable climate.

“I am certain that 2021 will be a year of climate change-related disasters,” said Alexey Kokorin, head of the Climate and Energy Programme at the World Wide Fund for Nature Russia.

“However, I can’t tell you which kind of disasters. We could be talking about drought in the North Caucasus, flooding in the Far East, or melting permafrost causing bridges and buildings to collapse. This sheer unpredictability really is the central problem of climate change.”

Shifting geopolitics

One unknown factor is how the Russian government will respond to the unfolding climate crisis in the year ahead.

Though the Kremlin ratified the Paris Agreement in October 2019, its obligations under the treaty — which commits signatories to reduce emissions from a baseline of 1990 levels — are limited as Russia’s emissions fell sharply with the collapse of the Soviet-era manufacturing sector after 1990.

While the Russian government has increasingly spoken of climate change as an urgent threat, the country’s emissions are projected to rise slightly by 2030.

“I don’t expect anything from the government,” said climate striker Makhichyan.

“They’ve been talking about climate action for a decade now, but nothing is being done in terms of carbonization.”

However, for Alexey Kokorin, of the WWF, shifting geopolitics will compel Russia to take action on climate.

“Biden’s win changes everything,” he said.

“When it was just the European Union pushing for action on climate, Russia could largely ignore it. But Biden will try to build a broad coalition of states that support new climate commitments going beyond the Paris Agreement, bringing in Canada, China, Japan and South Korea. If that happens, Russia will have to fall into line to avoid total diplomatic isolation.”

Kokorin suggested that international climate action could also force some of Russia’s biggest private companies to pick up some of the country’s climate slack.

“With the EU getting tougher on climate standards, it’s possible that large companies that export to the European market, like Severstal and Nornickel, may start investing in conservation and renewable energy projects to lower their carbon footprint and avoid potential climate tariffs. I could even see fossil fuel companies like Gazprom and Rosneft taking this approach.”

For some, there are also green shoots of optimism within Russian society itself.

“I do think ordinary Russians are becoming more conscious of environmental issues, and how their personal choices impact them,” said Green Patrol’s Pukalov, pointing out a huge rise in climate-related activism that is pushing the issue into the mainstream in Russia.”

“The picture is bleak, but there are causes for optimism,” he said.