Migrant children in Russian kindergartens are to begin learning the language of their adopted country as the authorities launch a teacher-training program to integrate the kids into society, and tackle a demographic problem.

Hundreds of thousands of migrant workers from Central Asia and the Caucasus have traveled to Russia each year since the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 in search of seasonal work. While many stay long-term, their children enter a school system that does not allocate resources toward teaching them Russian as a second language.

“It’s been a long-brewing problem that needs to be solved,” said Yekaterina Demintseva, who researches the integration of the children of migrants in Russia’s school system at the Higher School of Economics. “The government is finally starting to pay attention.”

Champions of teaching Russian as a second language have applauded the move, which arrived in the form of an Education Ministry tender this month allocating 11.3 million rubles ($174,585) to training kindergarten teachers through 2021.

But those same champions have also questioned the extent to which the measure will be effective. While all Russian children have the constitutional right to attend school, education experts say there is a deficit in Russian kindergartens. A recent official count indicated that nearly half a million children couldn’t attend kindergarten.

As a result of the long waiting lists and the fact that even locals face difficulties in getting their children enrolled, experts on the education of migrant children say that children who don’t know Russian from birth or whose homes aren’t Russian-speaking are often turned away from kindergartens on the basis that they won’t be able to learn effectively without the language.

“It’s a bit absurd,” said Demintseva of the allocation of funds to kindergarten teachers. “Of course it’s good for these teachers to have these skills. But the thing is that they will have very few children to teach.”

Experts instead argue that the resources ought to have been directed toward teaching Russian as a second language in elementary schools, because it’s there that teachers most often find students in their classes who aren’t proficient in Russian. And without specifically allocated resources, the task is taken on ad-hoc.

“I travel to schools across the country, and if I see anyone teaching Russian as a foreign language, it’s a great educator who is finding time to stay after school with these students,” Demintseva said.

While acknowledging that more work is needed, experts nonetheless see the move as a signal that the authorities have come around.

“If the Education Ministry is trying to prepare children to stay and work in Russia, then a lot more needs to be done and the problem needs to be looked at as a whole,” said Konstantin Troitsky, who runs the migrant children education program of the Civic Assistance Committee, a Moscow-based NGO that works with migrants and refugees. “But of course: any first step is good.”

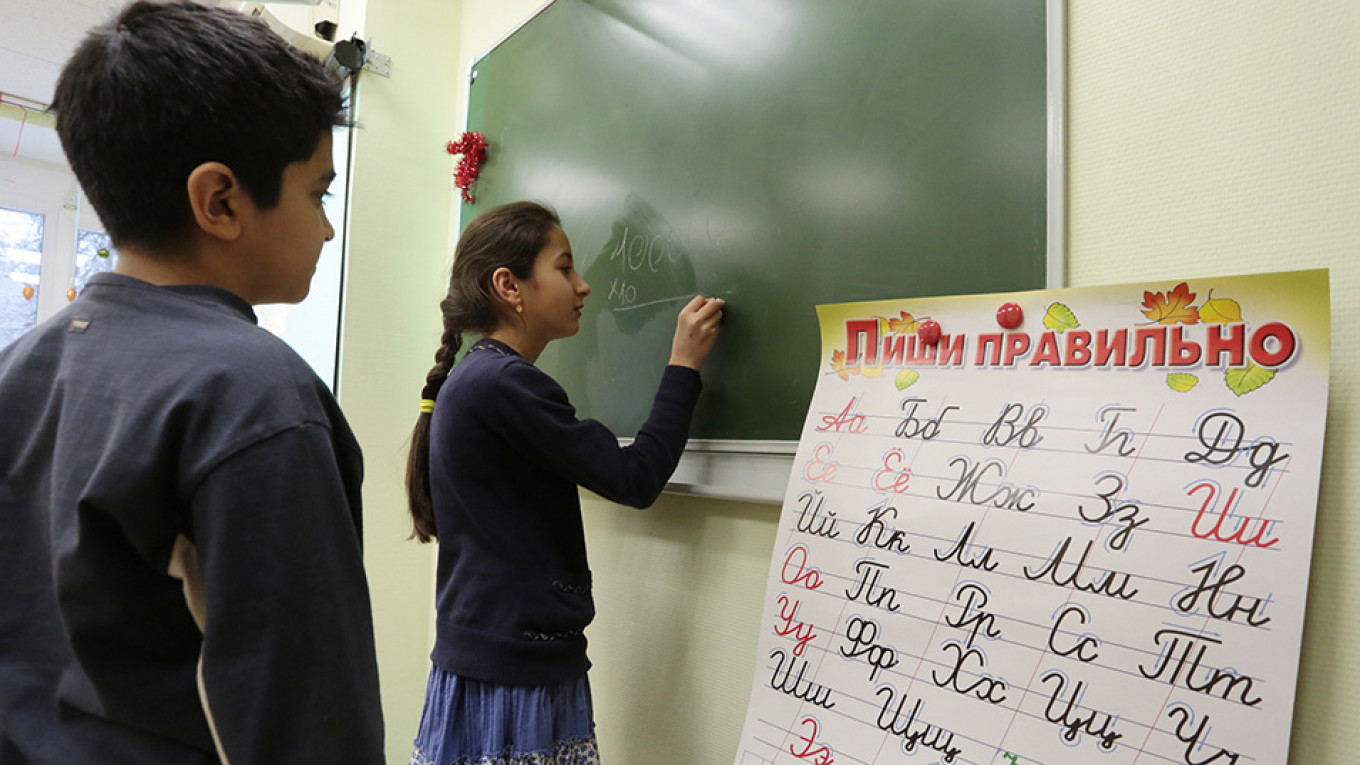

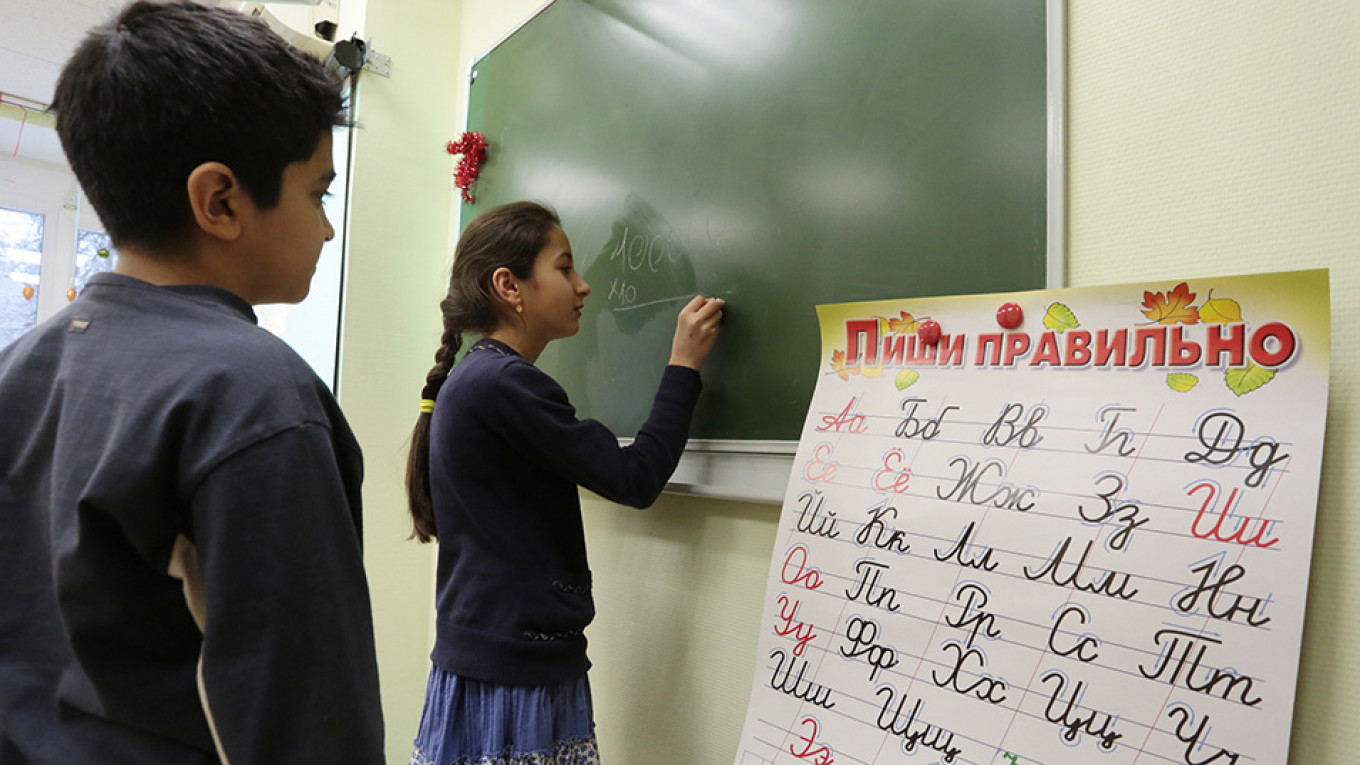

The first step toward integration is language. Maxim Kimerling / TASS

The first step toward integration is language. Maxim Kimerling / TASSThe first step toward integration has come as Russia faces another challenge — combating a falling population.

Last year, for the first time in a decade, migration was unable to offset Russia’s population decline after only 124,900 foreigners came to the country. To reach net growth every year, Russia needs to attract up to 300,000 people.

The lack of people is hampering Russia’s economy. Valery Elizarov, the director of the demographics department at Moscow State University, estimates that the country is losing about one million workers per year — the result of more emigrants than immigrants and a generational imbalance.

“The generation now reaching retirement age is much larger than the generation currently entering the workforce,” he said.

As Bloomberg News reported last year, this imbalance could decrease Russia’s GDP by as much as 1 percent per year.

Russian President Vladimir Putin has prioritized migration policy to replenish Russia’s workforce, formalizing an action plan last year for 2019-2025. In March, the Kommersant business daily reported that the Kremlin plans to attract up to 10 million Russian-speaking migrants over the six-year period. The plan is focused on Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Moldova and other post-Soviet states with Russian-speaking populations as so-called donor countries from which new Russian citizens could be recruited.

Experts, however, say the target is misplaced.

“The immigrants who wanted to come to Russia from those countries have already come,” said Karina Pipiya, a sociologist with the independent Levada Center pollster.

And if Russia in placing more of an emphasis on integration in its school systems, it shouldn’t limit itself to Russian-speaking immigrants, said Demintseva of the Higher School of Economics.

“We need to orient ourselves to all countries,” she said.

Pipiya, however, warned that language and cultural integration aren’t the only barriers that must be overcome. According to Levada’s latest figures, two-thirds of Russians believe that immigration should be reduced, even as the Kremlin is gearing up to import more people into the country. And while language was seen as an issue, it didn’t take precedence for Levada’s respondents.

“The most common response is that immigrants take our jobs,” Pipiya said. “And this is a problem that language integration alone won’t solve.”