Twelve big cats loll around the ring of the Moscow State Circus during a public rehearsal as Russia’s most famous animal handlers, brothers Ascold and Edgard Zapashny, train them to jump through flaming hoops.

Some stare at the men and growl quietly, while others ignore the trainers and play with their own tails. Eventually, a tiger performs the trick before slinking back and flopping down in its place.

“You can see that there is no need for any kind of violence to make the tiger jump through the hoop,” one of the brothers tells the audience. “It’s logical that if an animal has never seen fire it won’t be afraid of it.”

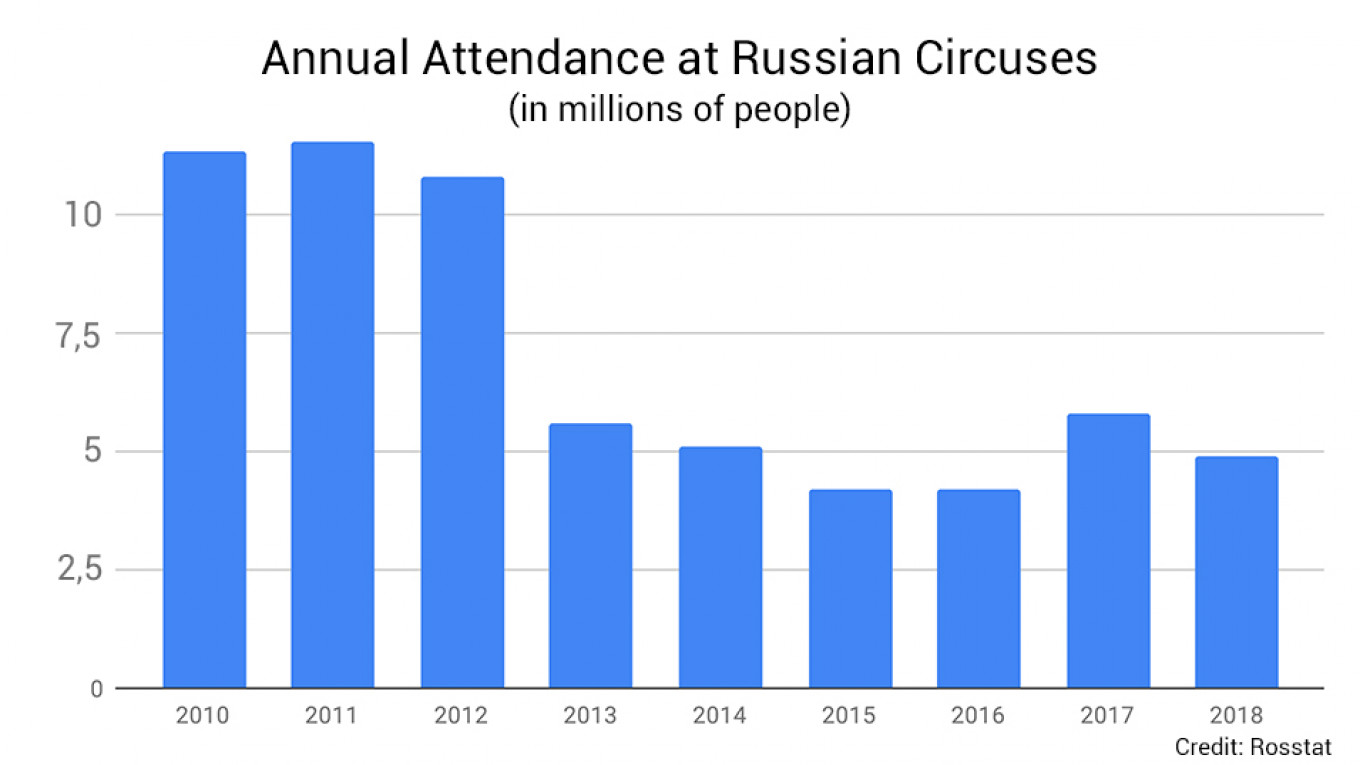

The circus has been elevated to an art form in Russia. Clowns Yuri Nikulin, Oleg Popov and Slava Polunin are household names, and almost 5 million people visited circuses last year.

But while many European and Latin American countries have banned the use of animals in circuses, along with parts of the U.S., Canada and France, Russia still clings to the tradition. In 2017, the state-run company Rosgostsirk that unites 38 static and five travelling circuses across the country received 1.3 billion rubles ($20 million) in state aid.

Animal rights activists in Russia are trying to change that by lobbying the government, staging protests and going on hunger strike. In November 2017, activists staged a two-week hunger strike outside the State Duma to campaign for the adoption of an animal protection law. And in 2018, there were several protests in Moscow to push for the law to be passed, as well as for the banning of animals in circuses.

Anna Filippova, a former campaigner for the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW), an NGO that closed its Russian branch in 2018 to focus on Africa, India and southeast Asia, told The Moscow Times that circuses are unnatural environments for animals and that forcing them to live and travel with the shows puts them under enormous stress.

“These animals don’t live in such conditions in the wild and they don’t travel around in trucks every month,” she said.

In one recent high-profile case, a bear performing with a circus in the northern republic of Karelia mauled its handler seconds after it had pushed a wheelbarrow across the ring.

Irina Novozhilova, the president of the VITA Animal Rights Center NGO, said that there are no circumstances under which it is acceptable to use animals in circuses.

“A circus is always walls with a terrifyingly small space for animals and endless moving in these horrible trucks,” she said.

Throughout the rehearsal at the Moscow State Circus, the Zapashnys tear down what they call “myths spread by animal nutcases,” including accusations that they buy exotic animals illegally, beat them to train them or keep them in bad conditions.

They declined requests from The Moscow Times to look around the animals’ living quarters.

The brothers are not only famous for their circus performances, they are also involved in politics. In 2012, they became trustees, or official representatives, of President Vladimir Putin. Later, they took on the same role for Moscow Mayor Sergei Sobyanin and the ruling United Russia party. In 2014, they signed an open letter from cultural figures to Putin in support of the annexation of Crimea.

While a poll conducted by the state-funded VTsIOM pollster this year said that 53% of Russians believe circuses should include animals, there are some signs that attitudes are changing.

Fewer people are visiting circuses, numbers of which are also falling. According to state statistics agency Rosstat, in 2018, 4.9 million people in Russia visited 60 circuses, down from 5.8 million people at 66 circuses the previous year.

In addition, “The Law on Responsible Treatment of Animals,” which had been pending for eight years, was passed in 2018 and goes into effect next year.

Activists say the law falls far short of what is needed because it doesn’t specifically ban beating circus animals to train them and is vague on minimum cage sizes. However, one of its authors, Vladimir Burmatov, told The Moscow Times that many of its bylaws still have to be finalized.

Magas, the administrative center of the republic of Ingushetia in Russia’s North Caucasus, in 2019 became the first place in the country to ban the use of animals in traveling circuses after its mayor, Beslan Tsechoyev, saw the beasts’ living conditions.

“Wild animals should be in their natural habitat, that’s what shows their beauty,” he told The Moscow Times.

Back at the Moscow State Circus, Vasiliy Timchenko is training a group of sea lions to stand up on their flippers and play with balls and hoops. He guides them with a stick with a ball attached to one end and rewards them with a fish when they do what he wants.

Timchenko, whose parents also trained sea lions, says he would never put his animals under stress.

“If a teacher is good students will rush to class, this is the same thing,” he said.

As rehearsals draw to a close, the audience is given the opportunity to ask the animals’ handlers questions. One young man wants to know why the show didn’t include the traditional Russian circus favorite of a lion riding a horse around the ring.

“We don’t do that anymore; people were starting to blame the trainers and feel sorry for the animals,” a handler replied.