Following Russia’s bombing of a drama theatre in the Ukrainian city of Mariupol in March, St. Petersburg-based artist Alexandra Skochilenko swapped supermarket price tags with stickers containing information about the attack that reportedly killed hundreds of civilians.

A fellow store customer reported her act of resistance to the police.

“I was extremely outraged by the slander I read because I worry a lot about Russian soldiers in Ukraine,” the 72-year-old informant claimed in testimony published by local media.

Soon after, Skochilenko, 31, was arrested for spreading “false information” about the Russian Army — a crime under new legislation that is being used to clamp down on information deviating from the Kremlin’s narrative of the war in Ukraine.

Skochilenko is one of dozens of Russians who have been criminally charged for anti-war actions or statements since the invasion began on Feb. 24.

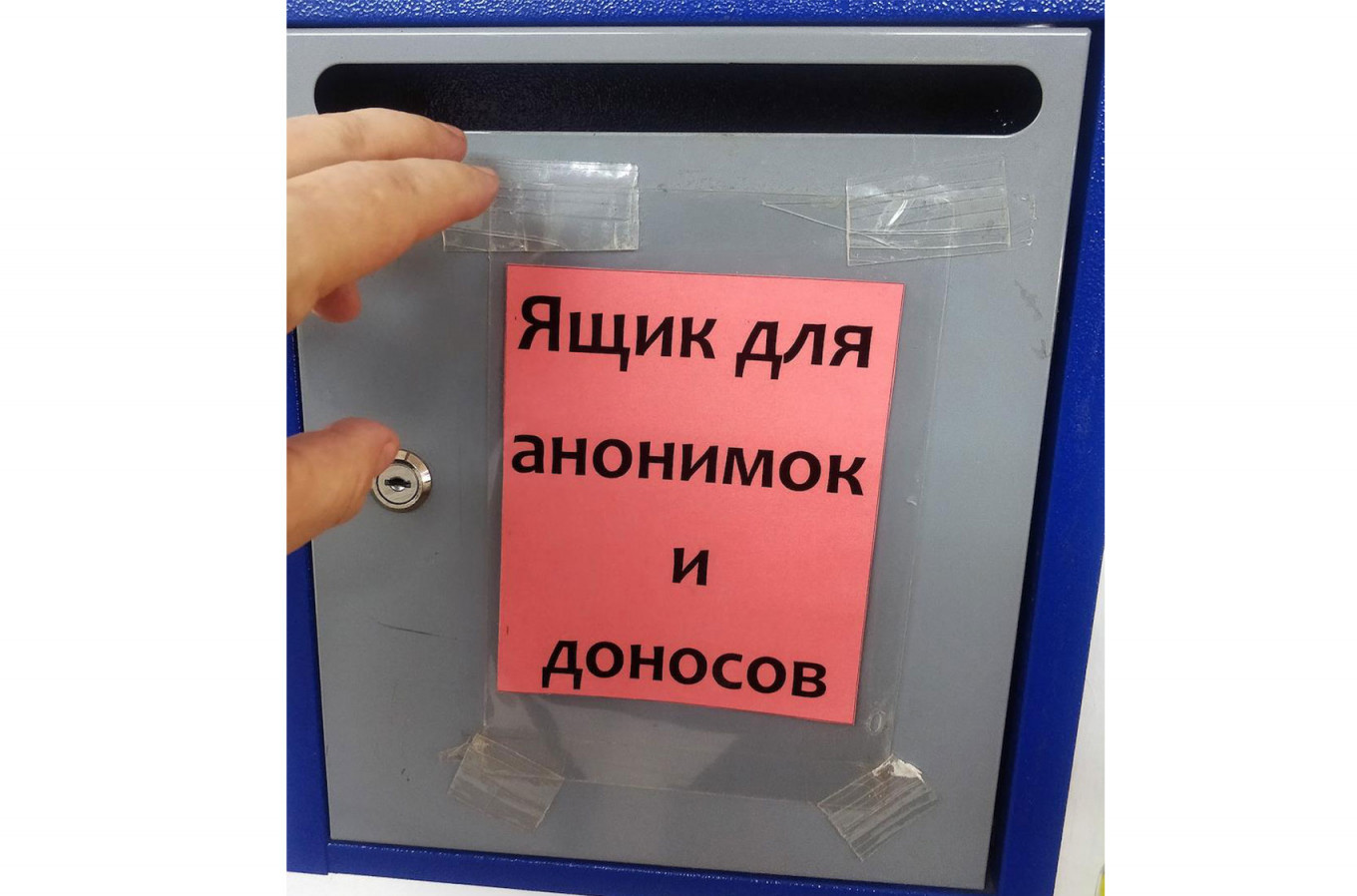

Many have been reported to police by family, neighbors and passersby in a trend analysts say harks back to Soviet denunciations — and is being actively encouraged by Russian authorities.

“We were very surprised that it happened because of the price tags,” Skochilenko’s friend Alexei Belozerov told The Moscow Times in a telephone interview. “I think the main goal of cases like this is to spread an atmosphere of terror and fear.”

A Russian court last month extended the artist’s pre-trial detention until the end of June despite her poor health. If found guilty, she faces up to 10 years in prison.

“We are dealing with distorted reality. In general, there’s nothing wrong with reporting offenses or сrimes, but such cases are very politicized. The [government’s] rhetoric has definitely changed,” Alexandra Baeva, the head of the legal department at protest monitoring group OVD-Info, told The Moscow Times.

In a March 16 speech, President Vladimir Putin said the “self-cleansing of society” would only strengthen the country, adding that Russians “will always be able to distinguish true patriots from scum and traitors and will simply spit them out like an insect in their mouth.”

Moscow student Elmira Khalitova was denounced by her father, who claimed she had been calling on people to “murder Russians.”

Khalitova, 21, told The Moscow Times that her father was driven to this dramatic step by a “TV propaganda frenzy,” as his political views are heavily influenced by tightly controlled state television channels and political shows.

Heavily intoxicated, he went to a police station and reported his daughter. She arrived soon after to file an official response and eventually convinced the police she didn’t say anything like this.

“Later, when he was sober, he said it was his civic duty. He explained it seemed to him someone had said that I urged [people to murder Russians]. And he had to report this. He also told me: ‘If you really called to murder Russians, I would go and report it [to the police] one more time’,” Khalitova said in an interview.

Following Putin’s comments, the A Just Russia party created a website where Russians can send in information about “unpatriotic” citizens. In St. Petersburg, the ruling United Russia party launched a similar campaign to counter “fake news.”

In the Urals region, pro-Kremlin television host Vladimir Solovyov and his team made the UralLive Telegram bot that allows residents to report information about supposed “anti-Russian” activities.

Likewise, authorities in the Western exclave Kaliningrad region asked people to report “intruders” to the Za Pravdu (For the Truth) Telegram bot — justifying the measure because of “increased cases of provocations and fraud” related to the war in Ukraine. Similar digital bots with the letter “Z,” a widespread pro-war symbol, have been created in the Altai, Belgorod, Penza, Saratov and Samara regions, as well as in Moscow.

Snitching on “politically incorrect” neighbors and colleagues was notorious in the Soviet Union. In many cases, people did it in the hope of ingratiating themselves with the government, for safety or out of personal spite.

Today, Russians mainly denounce others in the belief that they are helping to enact “some kind of justice,” said anthropologist Alexandra Arkhipova in a recent podcast with independent media outlet Meduza.

“This trend is worrying, though we don’t have the same scale of snitching and repression as in the U.S.S.R. The authorities perhaps would like us to think that other citizens are taking part in such repressive practices,” said OVD-Info’s Baeva.

More than 50% of the “disinformation” charges under the new law have been pressed in response to anti-war protests, and around 30% are based on online posts and statements, Arkhipova said.

Showing support for Ukraine — like displaying blue-and-yellow ribbons symbolizing the Ukrainian flag or anti-war posters in a window — has resulted in invitations to the police station at best, if reported by vigilant neighbors.

That was the case for Regina Ibragimova, a single mother from Ufa, who was denounced twice for her political views by a neighbor; and Mikhail Zheltonozhsky, a businessman from Bryansk, who was fined for “discrediting” the Russian Army after being reported by his neighbor as well.

Denunciations have also quickly become common within government agencies.

Yelena Kotenochkina, a deputy in Moscow’s Krasnoselsky District Council, called Russia a “fascist state” due to its invasion of Ukraine during an April council meeting.

When her anti-war statements came to the attention of State Duma deputies Alexander Khinshtein and Oleg Leonov, they denounced Kotenochkina to the Prosecutor General’s Office.

Her colleague Alexei Gorinov — also a deputy of the Krasnoselsky District Council — was arrested for spreading “false information” following the April meeting.

The two deputies now face up to 10 years in prison. Kotenochkina fled Russia and was placed on Russia’s wanted list.

“I received calls from concerned citizens who asked me: ‘Why does Kotenochkina, as a representative of the state, go against the government’s position? Who allows this?” Kotenochkina told The Moscow Times.

“Some people compare what’s happening today with the times of the Soviet Union,” she said. “It’s a fair comparison; people are put in prison for their opinions while the state encourages denunciations like in the 1930s.”