Boris Bondarev, a former member of Russia’s delegation to the United Nations in Geneva, now lives modestly in Switzerland with his wife and their kitten — and spends a lot of time on Twitter.

The ex-diplomat is unable to return to Russia after publicly quitting his job in May when he said the invasion of Ukraine was a “bloody, witless and absolutely needless ignominy” and slammed his former colleagues as liars and warmongers.

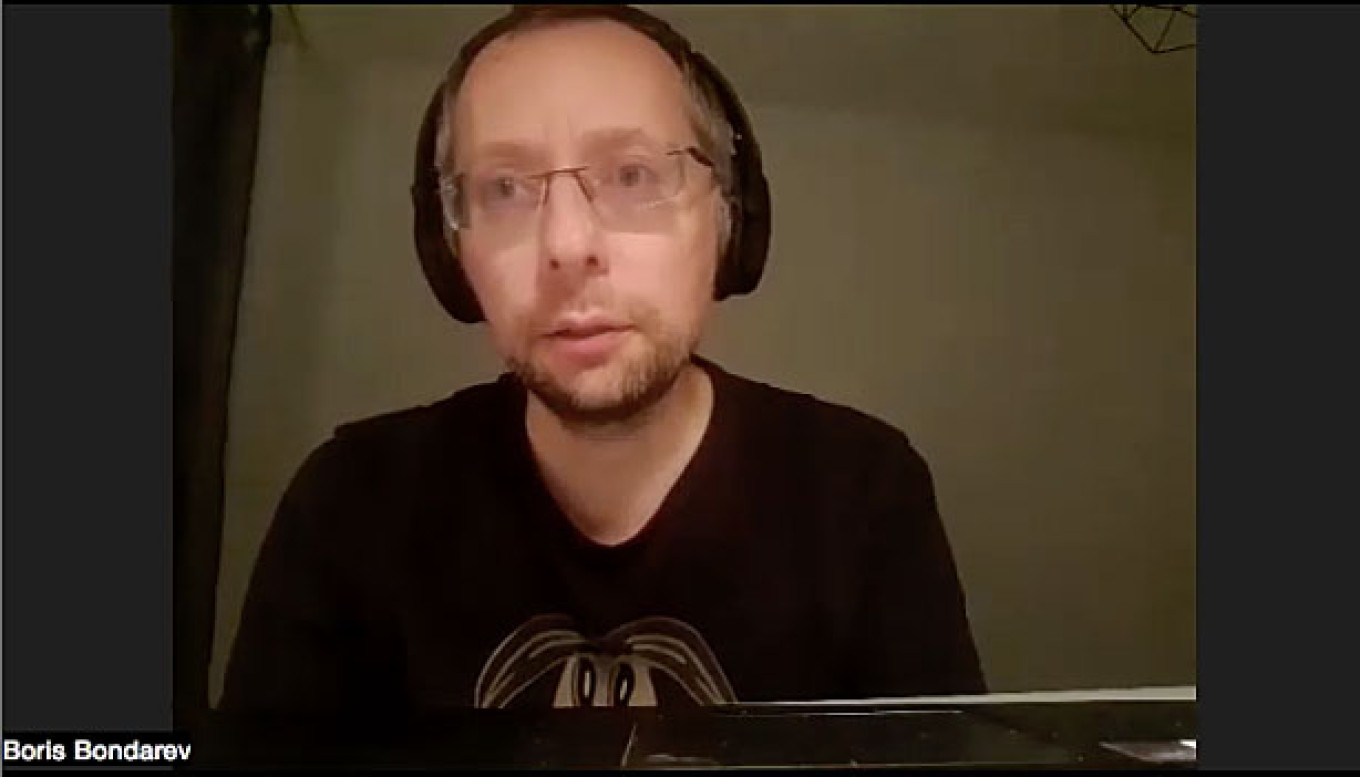

“I have a lot of free time,” Bondarev said in a Zoom interview with The Moscow Times. “I have not been working… so I am active on social networks.”

Bondarev, 42, was briefly thrust into the media spotlight when he quit his mid-level job in the Foreign Ministry, making him one of just a handful of Russian officials to resign as a result of the invasion of Ukraine in February.

Since then life has been far from glamorous as he picks fights on social media, takes long walks in the Alps and sends out CVs for jobs.

On Twitter, the former arms control expert has left sarcastic comments under tweets by ex-President Dmitry Medvedev and nationalist politician Dmitry Rogozin; had a public argument with the former U.S. ambassador to Russia Michael McFaul; posted lots of cat photos; and advocated for the creation of a political party to unite the thousands of Russians who now find themselves unexpectedly living in exile.

After his dramatic resignation, the former diplomat received asylum in Switzerland for which he said he was “very grateful.”

He also said he was provided with protection by the Swiss authorities due to the risk posed by Russia’s security services targeting him in a revenge attack.

He declined to disclose some details of his new life, including where exactly he was living for security reasons, though stressed he had a much simpler life now compared to when he was a diplomat on a Foreign Ministry salary.

When he left his diplomatic apartment in Geneva, he only took the absolute essentials, he said.

“I left my skis behind, for example. I don’t know who uses them now — or perhaps they are lying in a warehouse somewhere,” he said.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine came as a shock for Bondarev, just as it did to most Russian officials who were kept in the dark about the Kremlin’s plans.

Once the initial shock had passed, however, the overwhelming majority of officials fell into line and began to publicly express their support for the war.

But, for Bondarev, it marked a turning point.

“I had long been dissatisfied with the way the Russian government functioned, with the corruption, with the repression and the lack of transparent decision-making,” he said.

“[The war] was the impetus for action.”

Bondarev felt unable to resign immediately as he wanted to wait for his wife to travel to Moscow and collect their cat, Simeon, before he did so.

Once his wife and their cat were back in Geneva in May, he quit.

Bondarev’s condemnation of the Ukraine war as a “crime” and his personal criticism of Putin drew a rapid, angry reaction from Moscow, where Putin’s spokesperson Dmitry Peskov said that Bondarev was “no longer with us but against us.”

When the invasion began, Bondarev said that, while some of his colleagues in Geneva rejoiced, many looked ashen faced but ultimately said nothing as they feared losing their high salaries and the multiple other perks of being a diplomat.

While Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said in a May speech that there were “were no traitors among Russian diplomats,” Bondarev claimed that as many as 30 diplomats resigned from the Foreign Ministry in Moscow — including some with a military background — following the invasion of Ukraine.

“There are rational people in the Foreign Ministry as well,” he said.

Bondarev dismissed claims that he had been recruited by a foreign intelligence agency, pointing out that if he had been his handlers would likely have urged him to stay in post to enable the collection of sensitive information.

“Nobody recruited me,” he said.

Since leaving his job, Bondarev has been regularly sending out CVs and has written op-eds for well-known English-language magazines, including Foreign Affairs and The Economist.

“I was definitely very proud of the article in The Economist,” he said, adding that, when studying at Moscow university MGIMO, a training ground for diplomats and spies, articles from The Economist were used in exams.

“Maybe in the future, students will study my article,” Bondarev said with a smile.

The former arms control specialist said he has had a few discussions with think tanks about working with them, but has yet to take a full-time job.

Bondarev was critical not only of the level of expertise about the West in the Russian Foreign Ministry, but also about the West’s Russia experts.

“Do you think [a degradation of expertise] happened only in Russia? No. When the U.S.S.R. collapsed they thought there was no enemy and they could do whatever they wanted,” he said.

“Of course, good specialists remain, but there are some who write some very strange things.”

In his free time, Bondarev has been rereading Russian novels and hiking in Switzerland with his wife.

He said he dreams of returning to Russia.

“I write a lot: I write down my observations, conclusions about my work. Maybe it is fair to say that I am preparing proposals for the reform of the Russian Foreign Ministry and foreign policy,” he said.

While he would like to go back to Russia, he realizes this will not be possible until Putin’s regime falls and the war in Ukraine comes to an end.

“I hope and would like to apply my knowledge and experience in the future,” he said.