In the hour leading up to the February 12 ceremony, the Smithsonian’s airy Kogod Courtyard was abuzz with the excited chatter of distinguished guests and eager reporters. At the center of attention was a long, slender stage, backed with a deep indigo curtain and framed on all sides by pruned trees. Prominently displayed were two imposing oblong forms, hidden from view behind thick black shrouds but soon to be unveiled for all to see. These were the specially commissioned portraits of Barack and Michelle Obama, making their formal museum debut.

Related Content

As 10:00 A.M. drew near, a hush descended on the crowd. High overhead, the courtyard’s undulating translucent ceiling seemed a silent promise of evolution and modernity. Kim Sajet, director of the National Portrait Gallery, was the first to approach the podium.

“Every commissioned portrait involves four people,” she told the crowd: the sitter, the artist, the patron and the viewer. Having welcomed the 44th president and First Lady, Sajet stressed to her audience the importance of the viewer’s role in defining the legacy of a portrait.

“At the end of the day,” Sajet said, “the sitter, the artist, and even the donor will disappear. It is the audience that will remain.”

And in the setting of the National Portrait Gallery—a venue freely open to the public 362 days out of every year—the new official portraits will be sure to attract and influence a large audience indeed. “These portraits will live to serve those millions of future visitors looking for a mentor, some inspiration, and a sense of community,” said Sajet.

Smithsonian Secretary Skorton took the stage next, illustrating the power of portraiture with the story of Matthew Brady’s still-famous portrait of Abraham Lincoln (whose 209th birthday fittingly coincided with the ceremony). A photograph captured before Lincoln’s impassioned 1860 oration at the Cooper Union, Brady’s portrait spread like wildfire in newspapers and on campaign leaflets. The image of Lincoln proved instrumental in winning the trust of everyday Americans.

Secretary David Skorton expects these new portraits to make just as forceful an impact—in part because of their remarkable subject matter. Introducing the former First Lady, Skorton was unstinting in his praise. “Michelle Obama blazed a trail for women and girls of color,” he said, “and inspired countless women and men and children across the U.S. and around the world.”

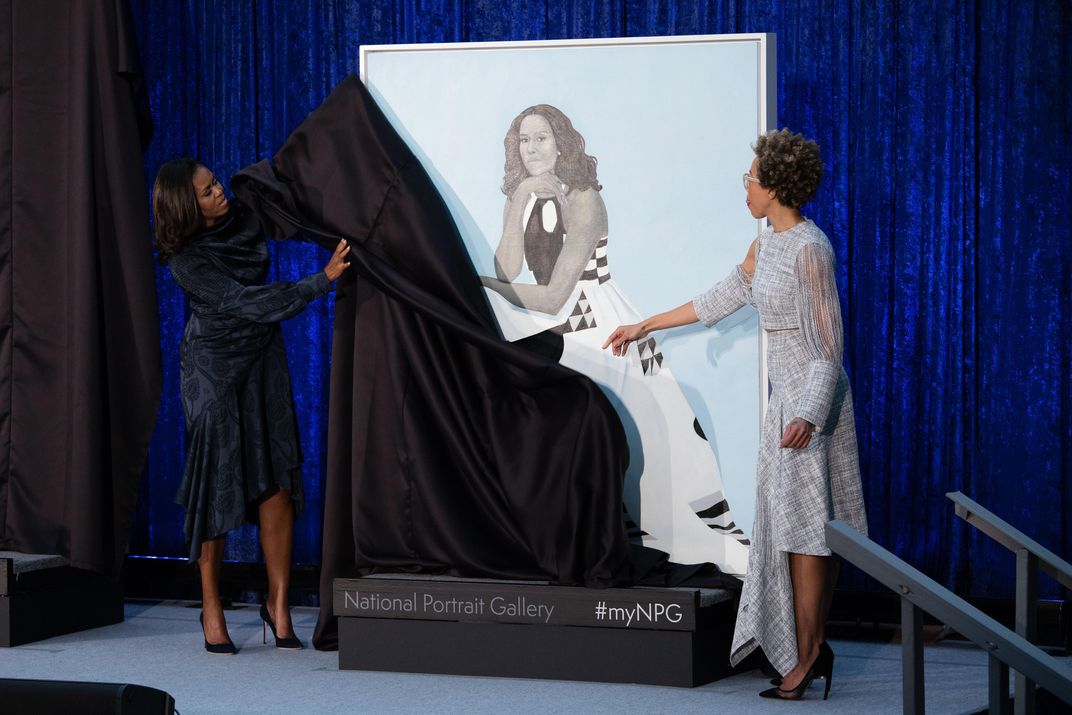

Next came the first big moment of truth: together with artist Amy Sherald, Michelle Obama set about removing the dark drape from her portrait. Members of the audience slid forward in their seats, craning their necks and priming their smartphones for action. Even Secretary Skorton was caught up in the suspense—as he later revealed to me, he deliberately avoided seeing the portraits in advance. “I wanted to be thrilled and have that moment where your breath draws in, like everybody else in the audience,” he said.

Immediately, the silent courtyard came alive—Amy Sherald’s depiction of Michelle Obama was startling in its boldness. In the painting, the First Lady, cool and confident in a flowing Milly dress, gazes resolutely outward. The sharp, vividly colored geometric designs flecking the dress, taken with Mrs. Obama’s exposed muscular arms and piercing gaze, give her the look of a strong and courageous leader. A sedate pale blue background seems to recede as the portrait’s subject takes center stage.

Approaching the microphone after taking it all in, Michelle Obama was visibly emotional. “Hi, Mom,” she said to her mother Marian Robinson, seated in the front row. “Whatcha think? Pretty nice, isn’t it?” Mrs. Obama went on to praise her mother, and her grandparents, who, she told the audience, made innumerable personal sacrifices for her. “I am so grateful to all the people who came before me in this journey,” she said, “the folks who built the foundation upon which I stand.”

Michelle Obama said she and Amy Sherald hit it off in a flash when the cutting-edge portraitist first visited the White House. “There was an instant kind of sistergirl connection,” Mrs. Obama told the audience. “Amy was fly, and poised, and I just wanted to stare at her a minute. She had this lightness and freshness of personality.” She recalled gleefully that Sherald had singled her out from the beginning. “She and I, we started talking, and Barack kind of faded into the woodwork,” Michelle Obama said, with a quick glance at her seated husband.

Amy Sherald herself took the mic next, thanking Mrs. Obama “for seeing my vision and being a part of my vision.” Sherald described her conceptual approach to portraiture, and the stylistic choices she made to fashion from the reality of Michelle Obama an immortal, inspirational “archetype.” “You are omnipresent,” she said of the former First Lady. “You exist in our minds and our hearts in the way that you do because we see ourselves in you. What you represent is an ideal: a human being with integrity, intellect, confidence and compassion. A message of humanity.”

A smile on his face, Secretary Skorton returned to the podium to introduce President Obama and his portrait, painted by Kehinde Wiley. “You know better than anyone your wife is a tough act to follow,” Skorton told Mr. Obama, drawing laughs from all over the courtyard.

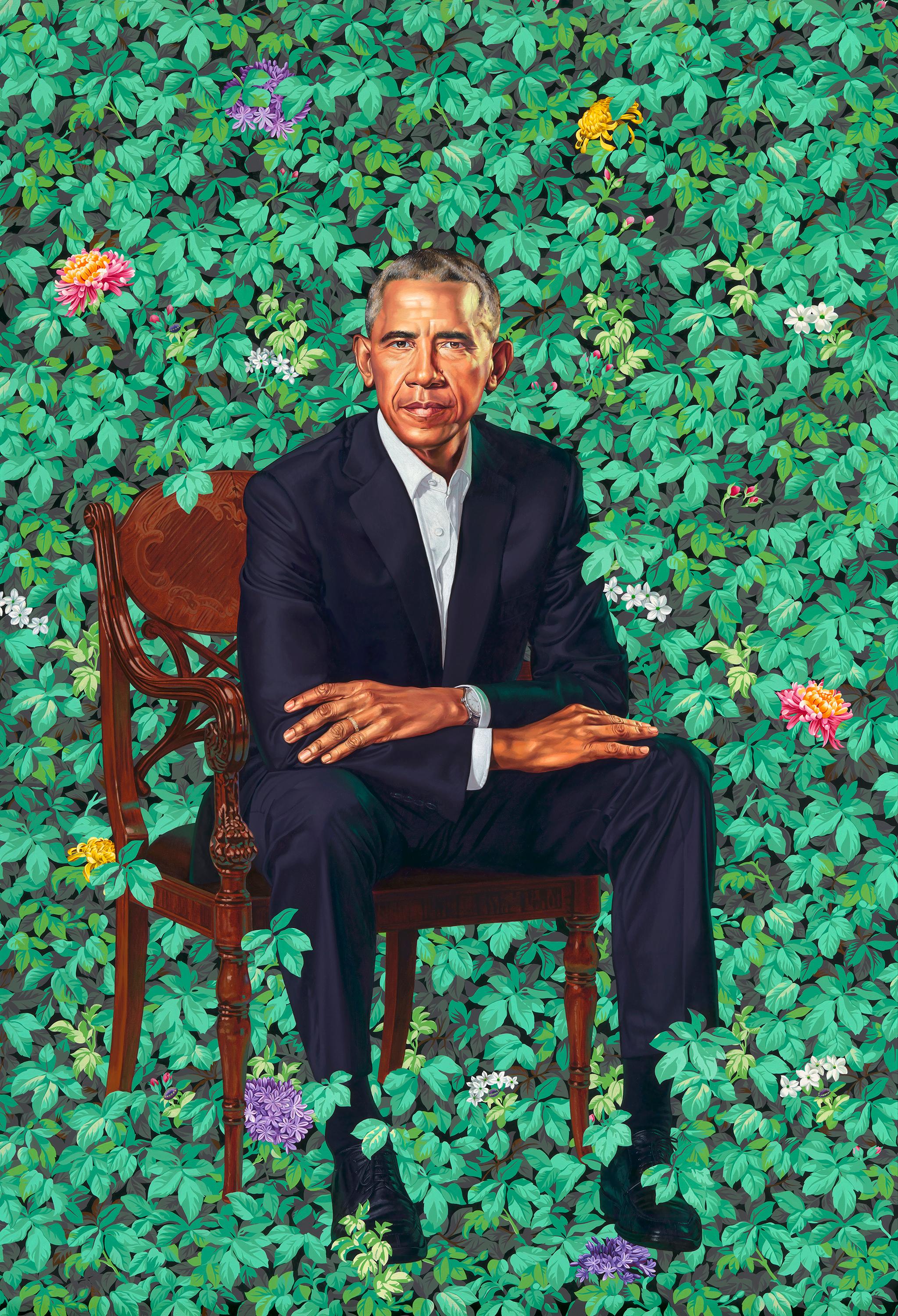

As Barack Obama’s portrait was exposed with the same dramatic flourish as that of his wife had been, the former commander in chief was quick with a quip: “How about that?” he said into the mic. “That’s pretty sharp.”

Kehinde Wiley set the image of a serious, seated Obama against a lush backdrop of leaves and blossoming flowers, which seem to have a personality all their own, threatening to consume him. The cryptic but compelling portrayal of a pathfinder president met with wide approval from spectators.

President Obama’s speech first soared with his now famous oratorical style, reminding his audience to “soak in the extraordinary arc we’re seeing” in racial justice efforts in the U.S., and echoing his wife’s wonder at the fact that young African-American visitors to the portrait gallery will now have male and female role models to show them that they too can climb to the highest levels of American government.

But then Obama switched to humor, recounting his experience working with Kehinde Wiley in colorful terms. “Kehinde and I bonded maybe not the same way” Michelle and Amy had, he said, “this whole ‘sistergirl. . .’” The crowd erupted in laughter. “I mean, we shook hands, you know. We had a nice conversation,” the president went on wryly. “We made different sartorial decisions.” (They also made different sartorial decisions on the day of the ceremony—Obama was clad in a conventional suit and muted mauve tie, while his portraitist wore a bold windowpane jacket and a rakishly unbuttoned black shirt.)

The former president noted that while he usually had little patience for photo ops and the like, he had found the artist a pleasure to work with—even if Wiley did insist on including realistic depictions of his gray hair and large ears that the president would have preferred to avoid. Egging Wiley on, Mr. Obama claimed to have talked the portraitist out of “mounting me on a horse” or “putting me in these settings with partridges and scepters and chifforobes…”

Upon stepping up to the podium himself, Kehinde Wiley playfully assured the audience that “a lot of that is simply not true.” He then took a moment to marvel at the occasion of the ceremony—“This is an insane situation”—before delving into his personal artistic approach to capturing the president.

Famous for setting ordinary African-American subjects in lavish scenes, elevating them, Wiley could afford to take a more measured approach with Obama, a figure who would already be known to nearly every American museumgoer. Opting for clear, crisp symbolism, Wiley surrounded the president with flora corresponding to geographical locations linked with phases in his life. “The chrysanthemum is the state flower of Illinois,” Wiley noted, and “there’s flowers that point towards Kenya, there’s flowers that point towards Hawaii.”

In this way, Wiley sought to capture the tension between the history behind Obama and Obama himself. “There’s a fight going on between him in the foreground and plants that are trying to announce themselves,” Wiley explained to the crowd. “Who gets to be the star of the show? The story or the man who inhabits that story?”

With spirited applause, the festivities came to a close, and Smithsonian Institution personnel and the artists braced themselves for journalists’ questions as Mr. and Mrs. Obama and their guests of honor (including former Vice President Joe Biden and a few celebrities such as Tom Hanks) discreetly departed the premises.

Secretary Skorton was visibly delighted at how the event had turned out. “My first impression, for both portraits, was that they were the best of what the Portrait Gallery has to offer,” he told me. “Not just a photograph, if you will, of the subject, but an interpretation, not only of the subject, but of the world around us, and the world that created the fame of those subjects.”

Portrait Gallery director Kim Sajet was of a like mind. “It’s fascinating,” she says, “when you go through and you look at official presidential portraiture, how it is evolving and changing. There was a moment where people thought it was sort of old hat to do figuration, but the truth is, we’ve always been drawn to doing pictures of people, and I think it’s evolving and becoming even more important.”

Dorothy Moss, who will preside over the new additions as curator of the Portrait Gallery’s “America’s Presidents” exhibition, is excited to see what possibilities these striking contemporary portraits will usher in for the museum. “These are portrait artists who are really pushing the genre in new directions,” she tells me, “and they are representing subjects who in terms of race have not necessarily been represented in formal portraiture in the past. I think that these artists are going to change the face of the Portrait Gallery with these presidential commissions.”