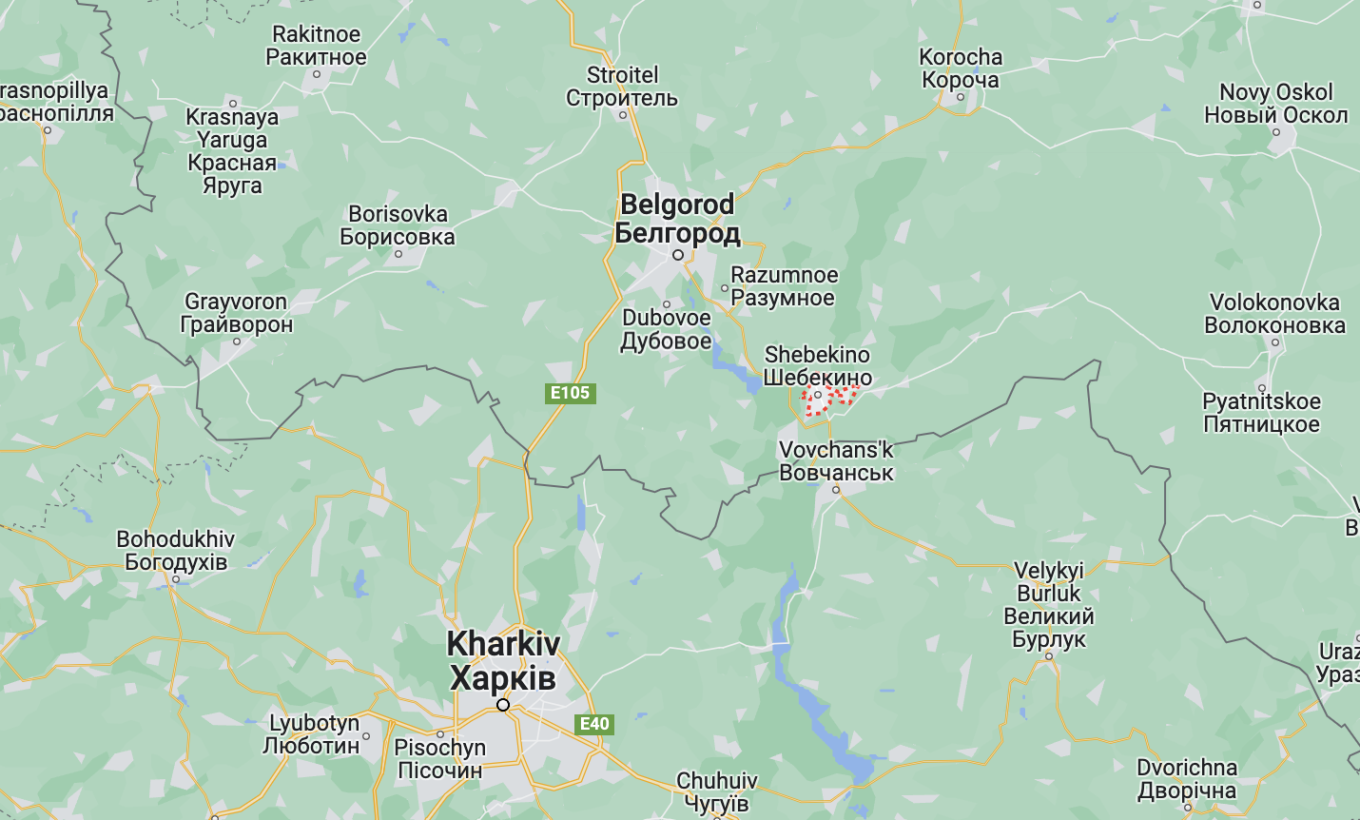

SHEBEKINO, Russia — Weeks of relentless shelling have turned this once-thriving district center near the Ukrainian border with a pre-war population of about 40,000 into a ghost town.

Rubble and broken glass litter the empty streets, and in the town’s central square, signs of shelling are visible on the building facades.

Not far from there, the police station has been turned into a blackened ruin after being hit by a Ukrainian rocket. A burning smell emanates from the local paint factory, which has been on fire for the past few days.

The eerie silence is broken by the occasional sound of artillery fire in the distance.

“That’s our guys shooting, don’t worry,” says Dmitry, 49, a Shebekino resident who has learned to distinguish the sound of friendly artillery from incoming shelling: Ukrainian army positions are located just across the border, only six kilometers away.

After evacuating his family a few days earlier, Dmitry decided to join the local territorial defense force, a volunteer unit that patrols the streets, protecting the city from looters and Ukrainian saboteurs.

“The enemy speaks the same language we do, so it’s hard to identify them,” said Dmitry, who remains confident in his ability to spot potential infiltrators.

“We know everyone here; if someone is not one of our own, we spot him immediately,” he said.

The police have apparently been unable to maintain law and order in the city, hence the need for territorial defense units.

“The situation is consistently heavy,” said Vladimir Karagodin, 52, a Cossack and local volunteer armed with a rifle, who says looting has been on the rise in recent days.

In addition to patrolling the streets, territorial defense volunteers have been helping the military evacuate border territories and distribute humanitarian aid to residents who decided to stay despite the constant danger of shelling.

Shebekino has been the target of sporadic bombing since last September, when Kyiv’s forces recaptured much of the neighboring Kharkiv region.

But in recent weeks, the frequency and intensity of the attacks has increased dramatically. In May, the Belgorod region was shelled 130 times, killing eight people and wounding 60, according to official statistics. And in the first week of June, over 1,000 apartments in Shebekino were damaged or destroyed.

According to military analysts, the intensified attacks on the Belgorod region are part of Ukraine’s summer counteroffensive and aim to force Russia to concentrate troops on the border, thus weakening its defenses elsewhere on the frontline.

Ukrainian officials have never acknowledged responsibility for the attacks, which escalated at the beginning of June, sparking the mass evacuation from the Shebekino district.

Many of the residents still remaining — about 2,700, according to the latest official figures — have been left without electricity or running water.

“They tried to convince me to leave, but I said no, I am old, I have a dog, I am very sick,” said Liudmila Nikulina, 73, one of the few residents who stayed behind, as she ventured outside to meet volunteers bringing her food and other essential goods.

It has now been more than a week since Nikulina was able to communicate with her loved ones due to disruptions with the telephone network.

“Tell them I am alive and well,” she asked the volunteers, handing them a sheet of paper with her relatives’ phone numbers.

Despite the one-time compensation of 10,000 rubles ($120) promised by the local administration to residents of areas affected by the shellings, many accuse the authorities of not doing enough.

“They forgot about us, we were left alone,” said Pavel, a local volunteer who asked that his name be changed for security reasons.

He and his girlfriend were forced to flee their apartment after a bomb hit the roof, destroying part of the staircase. Like 4,000 other Shebekino residents, they now live in a temporary shelter set up in a university dorm in the regional capital, Belgorod.

Despite the widespread discontent toward local authorities, explicit criticism of Russia’s leadership for the invasion of Ukraine remains very rare among Shebekino residents.

“When is Biden going to stop fooling around?” said Nikulina. “It’s him, the director of all this. And that other Ukrainian clown.”

“If we hadn’t done it, they would have attacked us first,” said volunteer Pavel. “We simply took the first step.”

Over 4,000 evacuees from Shebekino are reportedly living in temporary shelters in Belgorod city. Thousands more have been sent to shelters scattered across the region and in Russia’s other federal subjects, while the lucky ones are staying with friends or relatives.

“I feel emotionally exhausted, I have no words or tears left,” said Elena, 42, who fled Shebekino the day before with her five-year-old son Matvei, leaving behind her job, grandmother and cat.

“I feel sorry for grandma, she didn’t want to leave,” Elena said. She is queuing in front of a sports arena in Belgorod’s city center, which was converted into a temporary shelter for the thousands of evacuees from the Shebekino district.

Here, Red Cross volunteers hand out compensation for pensioners, people with disabilities and families with small kids.

“I now go wherever some help is offered,” added Elena, who lost her job and now lives with her son in the sports arena.

“We used to have plans for the future, some hopes,” echoed Tatyana, 60, another woman standing in line who asked that her name be changed for security reasons.

She is from Novaya Tavolzhanka, a village that became the theater of heavy fighting between the Russian army and anti-Kremlin militias made up of Russians who carried out a cross-border incursion earlier this month.

While Belgorod Governor Vyacheslav Gladkov has said the village is now fully under Russian control, residents are still not allowed to return.

“They say it is too dangerous to go there, but they don’t tell us why,” Tatyana said. “Do the saboteurs control our road?”

Like many other evacuees, Elena and Tatyana said they have no idea when they will be able to return home.

“When they told us that this was a special operation that would last two or three weeks, we were a bit worried,” Elena said, using the Kremlin’s preferred term for the war.

“But now it’s the second year, my house is destroyed and it’s a different situation,” she said. “This is war.”