Jailed Kremlin critic Vladimir Kara-Murza’s new charges that could extend his 25-year prison sentence even further have brought the fight to free him from Russian prison back into focus.

But while Kara-Murza’s family and colleagues push for his release via a prisoner exchange, wider diplomatic dynamics risk hampering their efforts.

Kara-Murza, 42, a critic of the invasion of Ukraine, was convicted last year of treason and other charges that he denies and has been held in a punishment cell in a Siberian penal colony since January.

His family says his health has deteriorated in prison due to a nerve condition resulting from the two poisoning attempts he survived in the 2010s. The death of fellow dissident Alexei Navalny in an Arctic prison in February intensified fears for Kara-Murza’s condition.

The opposition politician and journalist now faces charges of failing to add a label indicating his ”foreign agent” status to his social media pages.

Though the charges are punishable with a fine, his wife Evgenia Kara-Murza said that she expects the courts to rule to extend his prison term — already the harshest sentence handed to a political prisoner since the fall of the Soviet Union.

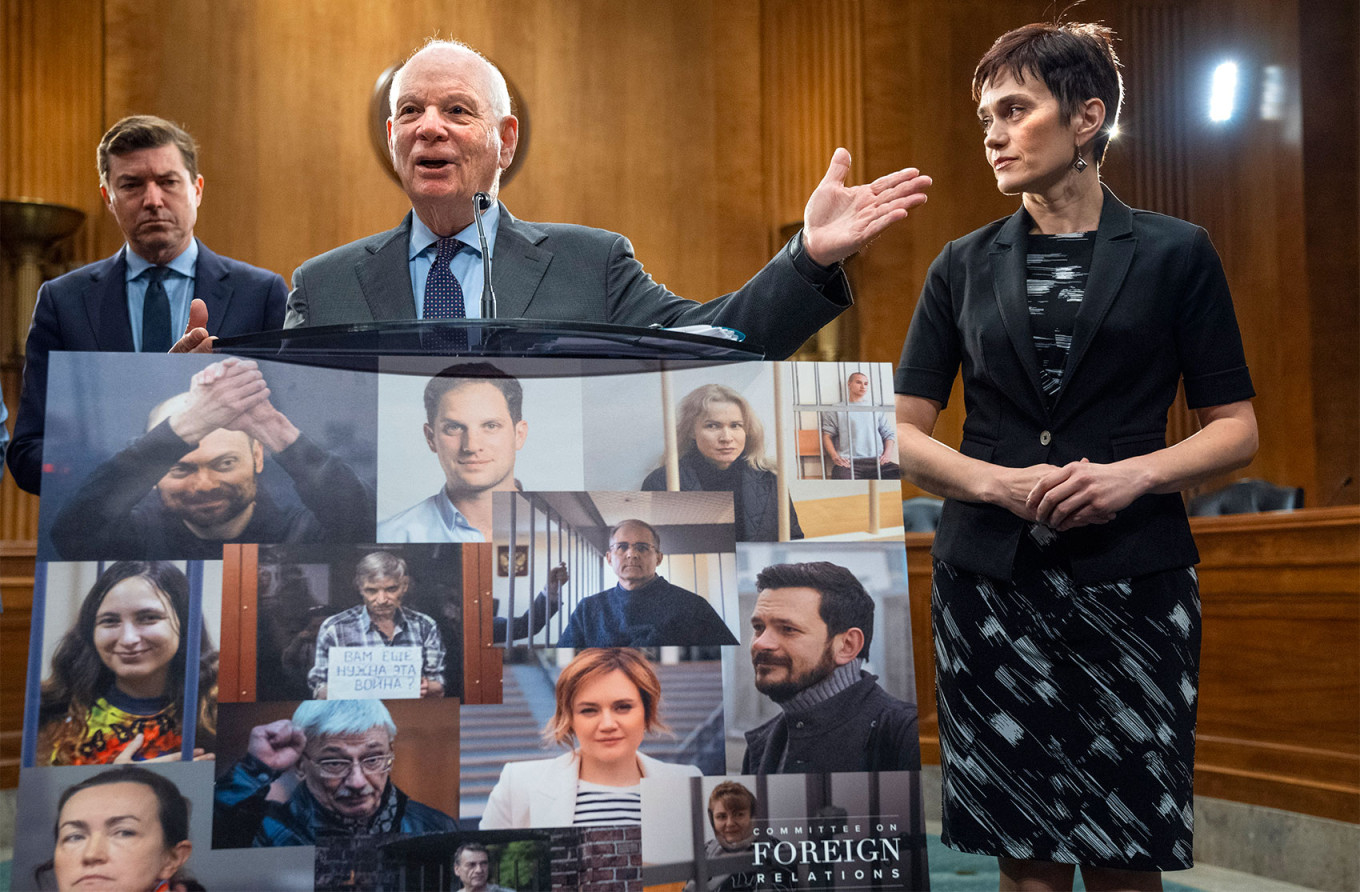

Last month, U.S. lawmakers joined calls for President Joe Biden to declare Kara-Murza “unlawfully and wrongfully detained,” a designation granted to jailed U.S. citizens Evan Gershkovich and Paul Whelan.

Kara-Murza’s U.S. Permanent Resident status meets the requirements for a swap by Washington. But Washington has yet to use this power for him.

As he holds British and Russian passports, he could be swapped by London if the Washington route is blocked. Yet the British Foreign Office (FCDO), which has a firm embargo on prisoner exchanges, already ruled out a swap for Kara-Murza in February, a position that remains unchanged despite the new charges against him.

In response to The Moscow Times’ request for comment on Friday, a spokesperson for the British Embassy in Moscow reiterated the U.K. Foreign Secretary’s statement expressing outrage and calling again for Kara-Murza’s release.

Hostage negotiation is a confidential and often controversial policy area, as shown during last year’s exchange of U.S. basketball star Brittney Griner for Russian arms dealer Viktor Bout.

“The trade will only embolden Vladimir Putin to continue his evil practice of taking innocent Americans hostage for use as political pawns,” ex-U.S. Ambassador to Moscow Michael McFaul said at the time.

Others argued that negotiating directly with hostile states is often the only way to extract political prisoners.

“It’s a terrible choice to have to make but in the end, I come down on the side of releasing her, or getting her out of a Russian penal colony,” U.S. Senator John Cornyn (R-TX) said.

While U.S. prisoner swaps are enabled by a law known as The Levinson Act, Britain lacks similar legislation.

“The Levinson Act is a very specific piece of legislation,” a British MP said. “We do not have the same powers on prisoner swaps — we just do not have that in our legislation.”

With prisoner swaps off the table and ransoms frowned upon, the FCDO has to rely on diplomatic leverage to rescue political prisoners.

“We have set up a cross-team task force of officials from diplomatic, consular, sanctions and communications teams to consider and implement a range of levers designed to put pressure on the Russian regime,” a spokesperson for the FCDO’s Department of Complex Consular and Crisis Management told The Moscow Times via email.

After a two-year wait, U.K. Foreign Secretary David Cameron met Kara-Murza’s mother Elena Gordon and wife Evgenia on March 1. As they met, Navalny was being laid to rest in a Moscow cemetery.

Evgenia said she was “very grateful” for the conversation, but later told The Guardian: “Whether governments engage or not, the number of hostages and political prisoners is on the rise. The message they are sending is that if you end up arrested, it is your fault. Democratic nations are supposed to fight for their citizens.”

Evgenia Kara-Murza did not respond to a request for comment.

The British ambassador to Moscow raised Kara-Murza’s case with Russia’s first deputy foreign minister in January, the FCDO spokesperson told The Moscow Times.

“Our Deputy Head of Mission has raised it again on several occasions with senior officials in the Russian Foreign Ministry, most recently on 19 March,” the spokesperson added.

The FCDO stressed the importance of career diplomats Barbara Woodward, the British ambassador to the United Nations, and her Russian counterpart Vasily Nebenza in these talks.

Last summer, Woodward told The Independent that she had only spoken with Nebenza twice since the start of the war. Both times were to plead for Kara-Murza’s release.

A negotiated release could thus hinge on talks between a pair of diplomats whose working relationship has otherwise collapsed. Tit-for-tat diplomatic expulsions and incompatible positions on Russia’s war in Ukraine have made it much harder for Russian and Western diplomats to have the informal dialogues that were possible pre-war.

Lord Ahmad of Wimbledon hinted at a new development in February, telling the House of Lords that officials would continue to raise Kara-Murza’s case with “countries with direct influence over Russia.”

The FCDO confirmed to The Moscow Times that talks are happening “in multilateral fora” but declined to specify which countries are involved.

Third-party countries, particularly the Gulf Arab states, are playing a growing role in high-level prisoner exchanges. The UAE and Saudi Arabia reportedly facilitated the Bout-Griner trade, while Qatar has helped to free kidnapped Ukrainian children from Russia and Israeli hostages from Hamas.

Time is not on Kara Murza’s side, and his wife fears he is at risk of dying in prison due to deliberate abuse.

The Kremlin has repeatedly refused to allow Kara-Murza consular access to an independent doctor. Moscow’s Ambassador to London said these requests could only be decided by a Russian court and did not take Kara-Murza’s dual citizenship into account on this issue.

A change in administration in Whitehall could cause more delays. The Labour Party is widely expected to win the next U.K. election this fall due to discontent at 14 years of Tory rule, bringing in a new foreign secretary.

Evgenia Kara-Murza has been critical of the conveyor belt of foreign secretaries over the past two years.

“There was Liz Truss and James Cleverly and then was there someone else? I forget. And we only now finally get a meeting with Lord Cameron,” she told The Guardian in March.

It remains unclear whether the same officials would remain on Kara-Murza’s case in the event of a Labour victory. The FCDO did not answer this question.

It appears that talks are already taking place in parallel. Shadow Foreign Secretary David Lammy of the Labour Party met Evgenia during her last visit to London.

A spokesperson for the Shadow Foreign Cabinet declined to comment on those talks when contacted by The Moscow Times.

The U.S. has taken a different approach. In 2020, the Trump administration appointed Roger Carstens as Special Envoy for Hostage Affairs, a position he still holds despite the change in administrations. Castens is directly responsible for the cases of Whelan and Gershkovich, but not Kara-Murza.

“Continuity in policy is critical, both in the mission to ensure hostages return home and in caring for their fragile families,” Jason Rezaian, a journalist and former prisoner in Iran, wrote when calling for the Biden administration to keep Carstens.

The ordeal to free Kara-Murza recalls that of Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe, a British-Iranian national jailed by Iran on false espionage charges. It took the FCDO six years and five foreign secretaries to free her, with successive administrations accused of restarting the case from scratch.

Prisoners’ families can play a crucial role in negotiations. Special Envoy Carstens noted in an interview that relatives often come up with the winning strategies themselves.

In Zaghari-Ratcliffe’s case, it was pressure from her husband that eventually pushed U.K. officials to change their policy. Richard Ratcliffe camped outside the Foreign Office and went on a hunger strike to protest the treatment of his wife.

London eventually secured Zaghari-Ratcliffe’s 2022 release by paying a backdated 400-million-pound ($508 million) debt to Iran, which then-Foreign Secretary Liz Truss described as “a parallel issue.”

Evgenia Kara-Murza, who hasn’t spoken to her husband since last summer, said she refuses to give up on her fight to free him.

“I have fought by my husband’s side for many years. And I have seen him twice in a coma, looking like an octopus with tubes coming out of his body because none of his major organs worked. I will stand by his side for as long as it takes,” she said.

… we have a small favor to ask. As you may have heard, The Moscow Times, an independent news source for over 30 years, has been unjustly branded as a “foreign agent” by the Russian government. This blatant attempt to silence our voice is a direct assault on the integrity of journalism and the values we hold dear.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. Our commitment to providing accurate and unbiased reporting on Russia remains unshaken. But we need your help to continue our critical mission.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It’s quick to set up, and you can be confident that you’re making a significant impact every month by supporting open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Once

Monthly

Annual

Continue

Not ready to support today?

Remind me later.

×

Remind me next month

Thank you! Your reminder is set.