When the Kremlin sent troops into Ukraine in late February, many Westerners living in Russia started looking for an exit.

“When it first started, we were shocked because we honestly didn’t think it was going to happen,” said one U.S. woman and longtime Moscow resident.

“We were getting lots of messages saying we have to leave, it’s dangerous. Then there were also rumors going that the internet would be shut down, that there would be martial law, the borders were going to close,” said the woman, who requested anonymity to speak freely.

But some chose to stay – in spite of the warnings from embassies, pleas from friends and family, and the political and economic risks.

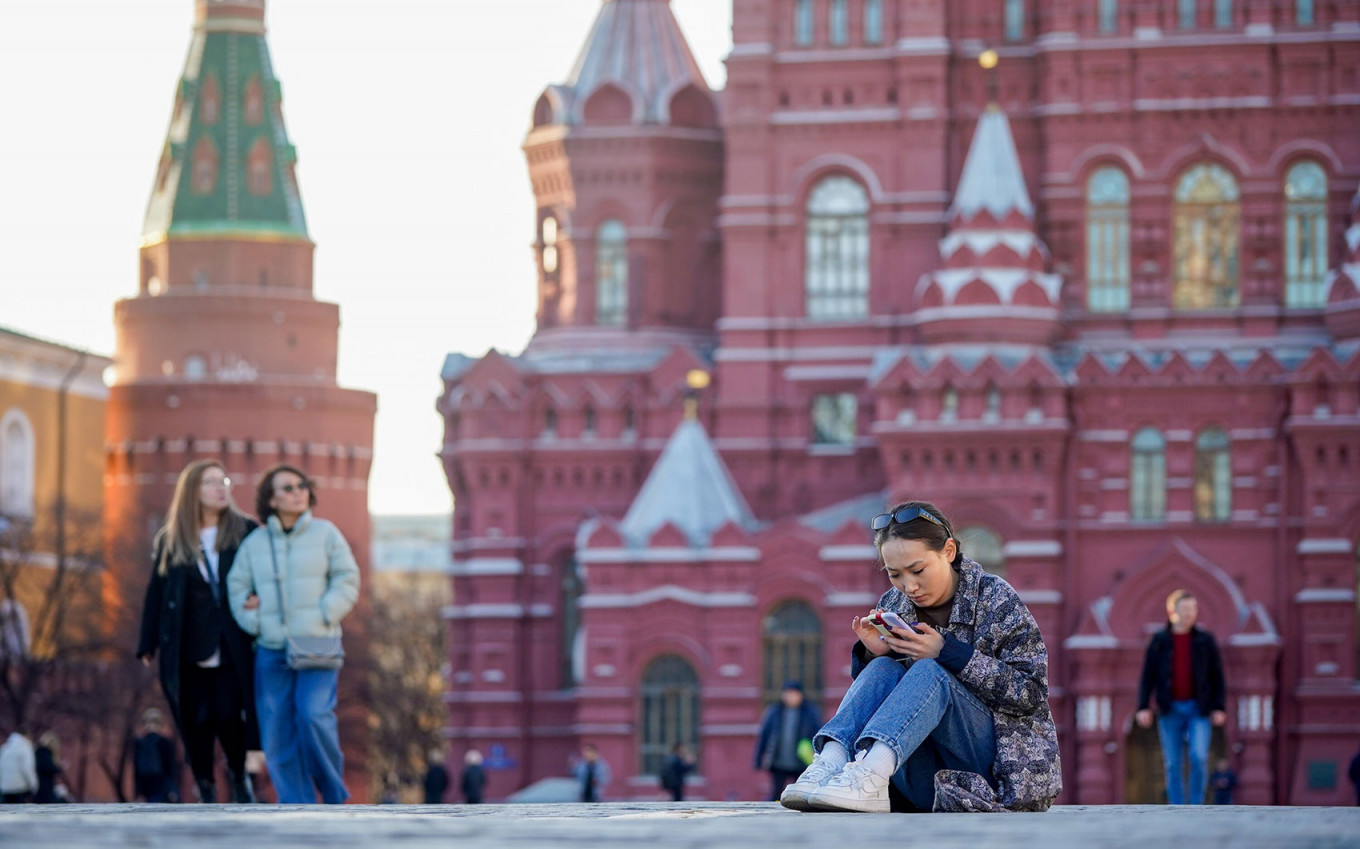

As Russia’s war in Ukraine passes the milestone of 100 days, Western residents in Moscow described a depleted city, where they were afraid to speak their minds, but where life – perhaps surprisingly – continued more or less as normal.

“We’d be the last ones to leave because we really do feel that Moscow is our home,” said the U.S. woman, who remained in the capital with her family.

None of the Westerners in Russia interviewed by The Moscow Times said they had feared for their physical safety since the start of the war. Nor did they report any instances of hostility from authorities or ordinary Russians.

But the military campaign has undoubtedly cast a cloud over their relationships with others, making them more cautious when voicing opinions.

“I think everyone is having to watch what they say around strangers,” said one American teacher in Moscow who also asked to remain anonymous.

“I am much more careful about what I say than I ever have been,” the U.S. woman said, adding that the atmosphere has made it harder to find like-minded people.

“It’s true that lately politics has gained a lot of interest: on the one hand it’s divisive and we have to be careful what we say, on the other hand I’m delighted that people are doing their own research,” said Léo Pigot, a French cheesemaker based in the St. Petersburg suburb of Gatchina.

Meanwhile, Western sanctions have almost completely isolated Russia from the global financial system and made it all-but impossible to transfer money between Russian and non-Russian bank accounts.

“I manage a life in two countries who have blocked financial flows from each other… Keeping an eye on the currency fluctuations and limitations imposed by the banks in either country has become a bigger part of my life than it ever was,” said Dutch national Kaj Vollenhoven, a manager in St. Petersburg for logistics firm Ahlers.

Other European and U.S. citizens in Moscow complained that financial isolation made accessing private healthcare facilities more complicated, as well as noting price rises for basic goods and plane tickets.

One Western diplomat who requested anonymity described what he called the “de-internationalization” of Moscow.

“It went from a city with most international brands, foreign language services, etc., to an increasingly provincial city,” he said.

According to research by NielsenIQ, the variety of consumer items, including personal care products and groceries, in Russian stores has fallen dramatically since the start of the war.

The sanctions have also taken a toll on businesses run by Westerners.

British national Helene Lloyd, head of the Tourism, Marketing & Intelligence consultancy in St. Petersburg, said her company felt the economic sting right away.

“We lost the vast majority of our clients as we had a lot of European clients and because our business is related to tourism and travel,” she told The Moscow Times.

While she said her business plans to stay in the Russian market, she added that they were also opening an office in the more neutral location of Kazakhstan.

“Realistically speaking, I do not see any great opportunities [in Russia] for at least five years, as it will take time to resolve the currently very strained relations,” she said.

While the changes have been significant, many other parts of everyday life in Russia remain – at least for now – largely unaffected.

“The shelves are still stocked with products, public transport still operates and many services which I used to utilize are still [working],” Dutch manager Vollenhoven said.

For the American woman, who has lived in Moscow for over 30 years – through the attempted coup of 1993, the wars in Chechnya and the coronavirus pandemic – today’s events are merely another historic storm to weather.

“Nothing lasts forever, and things one way or another are going to change,” she said. “What’s tragic is that it was a situation that… shouldn’t have happened.”

Vollenhoven said he plans to stay and adapt to whatever happens next.

“Russia will not go back the way it was anytime soon. The consequences it faces now are here for the long run. I do not try to predict whether things will get better or worse, or when. I believe this is simply impossible to predict,” he said.

“I trust in Russians’ everlasting persistence and adaptability.”