Half a decade has passed since Vladimir Putin annexed Ukraine’s Crimean peninsula. For Russia, the costs continue to mount.

The accession treaty signed to bring the Black Sea territory into Moscow’s fold is still unrecognized by most countries and the U.S. and European Union led a broad effort to punish Russia with sanctions.

Undeterred, Russia has kept integrating Crimea into its economy, investing billions in new power plants and building a giant bridge to the peninsula last year.

Most of the costs Russia has incurred have come from the U.S. and EU penalties, which have piled up every year since the annexation, with new ones added for alleged election meddling and other actions.

But the country and its residents — already suffering from low prices for oil, Russia’s main export — are also feeling the pain a drop in foreign investment and stagnating incomes. A recent survey suggests the public appeal of the annexation is starting to wear off.

Here are five charts that illustrate the cost of the takeover.

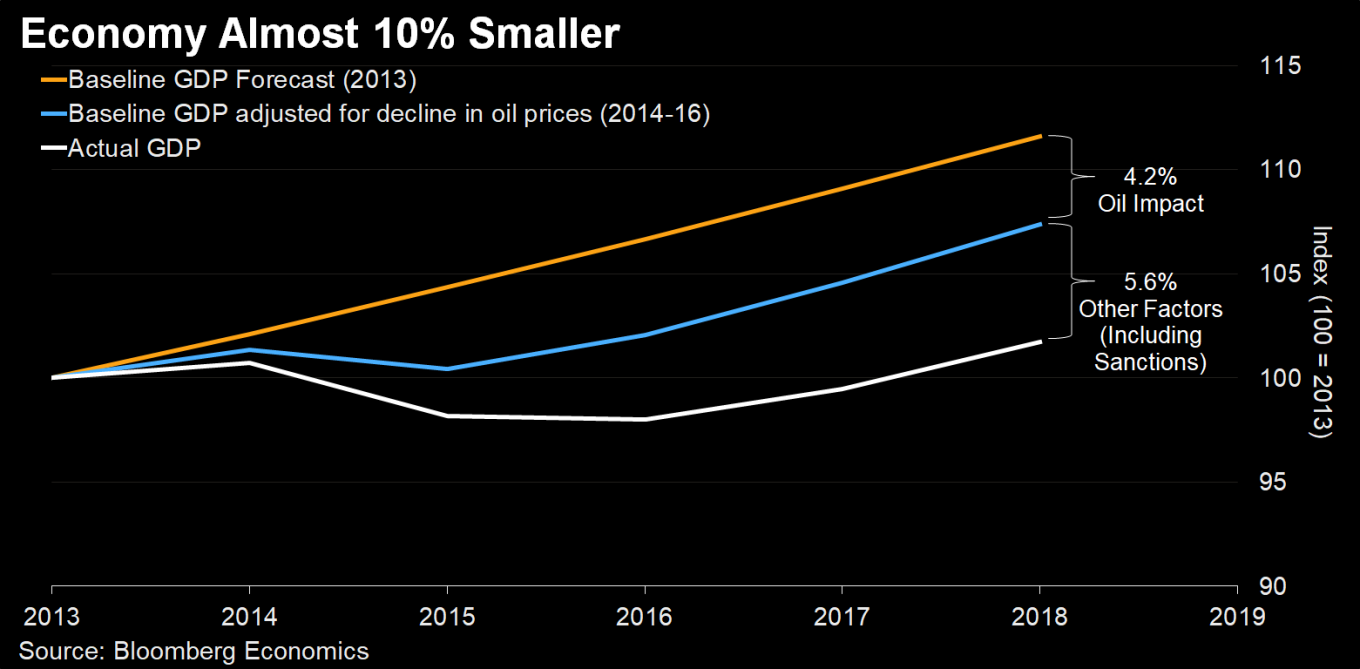

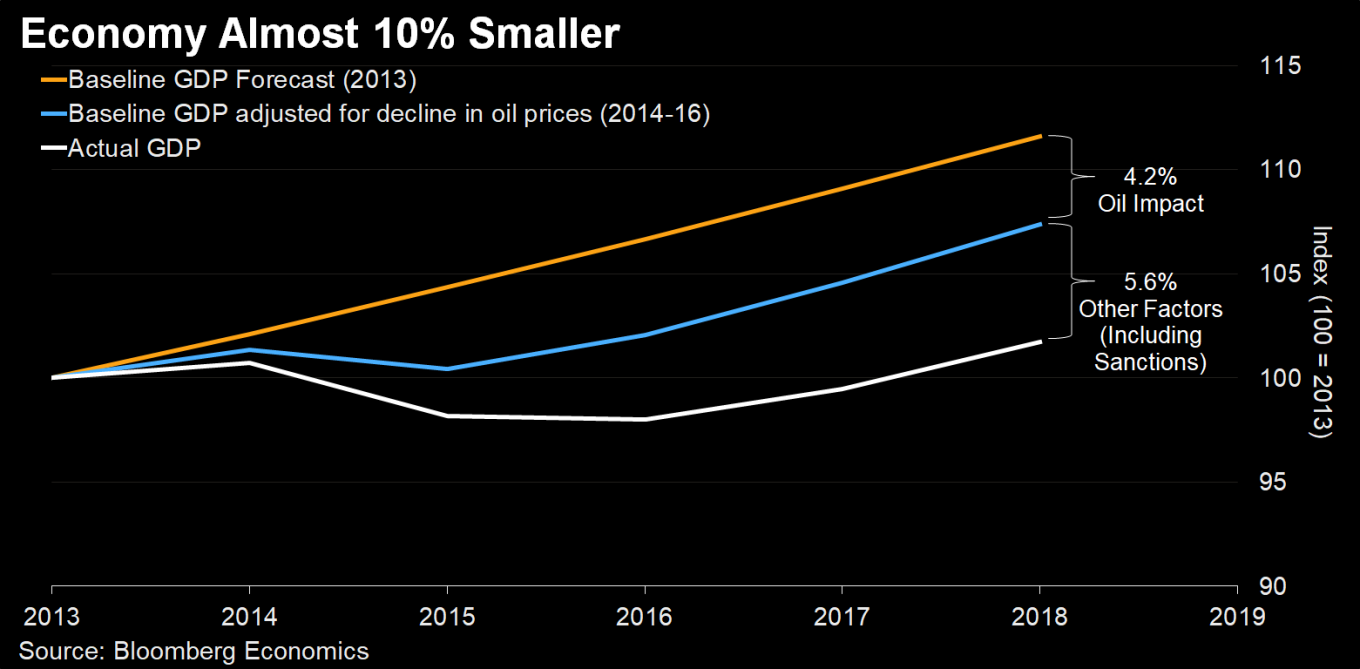

Analysts at Bloomberg Economics estimate that sanctions have knocked as much as 6 percent off Russia’s economy over the past five years. A study published by analyst Scott Johnson late last year found that the economy of the world’s biggest energy exporter is more than 10 percent — or $150 billion — smaller compared with what might have been expected at the end of 2013.

Four percentage points of that come from the drop in oil prices, but sanctions and other factors are to blame for the rest.

The sanctions drag isn’t likely to go away any time soon, and allegations that Russia meddled in the 2016 U.S. presidential elections mean it’s only likely to get worse.

The number of Russian companies and individuals who are subject to U.S. sanctions has quadrupled to more than 700 since 2014, and another bill is doing the rounds in Washington that could hit the country with a new raft of penalties this year.

The economic lull has meant less money is filtering through to paychecks of ordinary Russians. Average incomes have barely budged above 30,000 rubles a month ($459) since the Crimea takeover and slump in oil prices pushed the country into an almost two-year recession.

One region where incomes have grown is Crimea as wages increase from a low base to catch up with those in Russia.

After picking up a bit in 2017 when it looked like U.S. President Donald Trump might move to lift sanctions, foreign direct investment has dwindled and even turned negative in the second quarter of last year.

As the economic pressure takes its toll on ordinary Russians, the positive effect the annexation had on public opinion five years ago has started to wear off. A poll published on Thursday by the Moscow-based Public Opinion Foundation (FOM) found that just 39 percent of Russians think the takeover did Russia more good than harm, down from 67 percent at the end of 2014.