Even skeptics can no longer ignore the effects of climate change in Russia.

First, there’s the weather. Last year was the hottest on record; the ice in the Arctic is melting at a dramatic pace, as is the permafrost; while forest fires and flash floods have ravaged swathes of Siberia, and methane is spewing from a massive fountain in the eastern Siberian Sea.

Then there’s the data. Scientists and academics from Russia’s top research centers have long warned that Russia is warming at more than twice the global average and say this will only increase. Like their colleagues abroad, a majority link these trends to human activity and the unprecedented release of greenhouse gases over the past century.

In the past year, Russia’s government has finally admitted that climate change is a serious threat to Russia’s future and has drawn up plans for action.

However, Russian leaders have been reluctant to take steps to reduce the country’s greenhouse gas emissions. While this comes as no surprise — as Russia’s economy is largely dependent on fossil fuel exports — it also means the country is doing little to slow global warming.

Here’s an overview of Russia’s approach:

Emissions

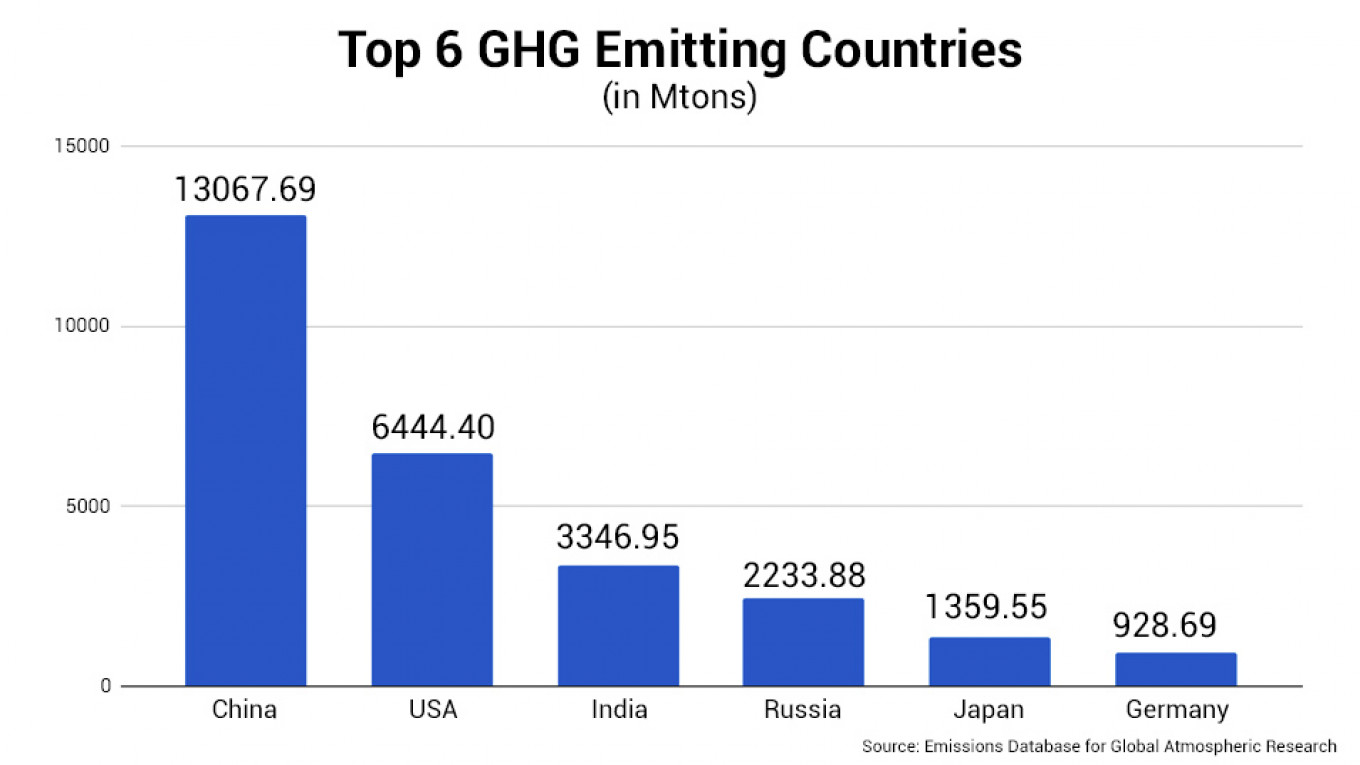

Russia is the fourth largest emitter of greenhouse gases in the world — after China, the U.S. and India — contributing around 4.6% of all global emissions. Moreover, its per capita emissions are among the highest in the world — 53% higher than China and 79% higher than the EU, though 25% lower than the U.S.

In a move of symbolic importance, Russia finally ratified the Paris agreement last October — which intends to keep global temperatures from increasing 2% above pre-industrial levels.

However, under its nationally determined contributions, Russia is not required to reduce emissions from current levels nor adopt a long-term carbon reduction strategy.

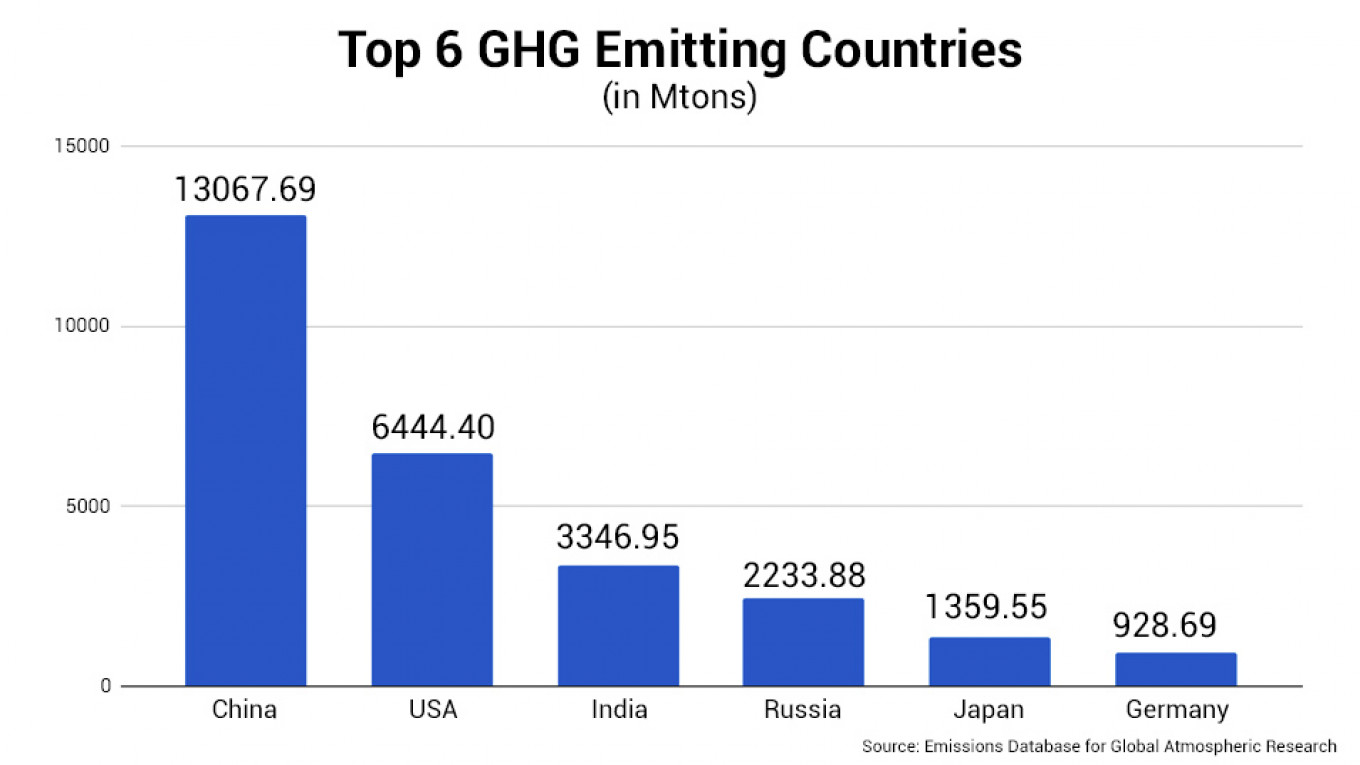

That’s because under the agreement, Moscow committed to emissions reductions of 25-30% from 1990 levels — but it has been well below those levels ever since the collapse of the Soviet Union and its industrial output in 1991.

In recent years, Russia’s emissions have been stable, and are projected to slightly increase by 2030.

For this reason, many environmental NGOs have called Russia’s climate policies among the world’s worst and say that if all countries were to follow Moscow’s approach, global warming would exceed 4°C, bringing catastrophic consequences for the planet.

Who’s to blame?

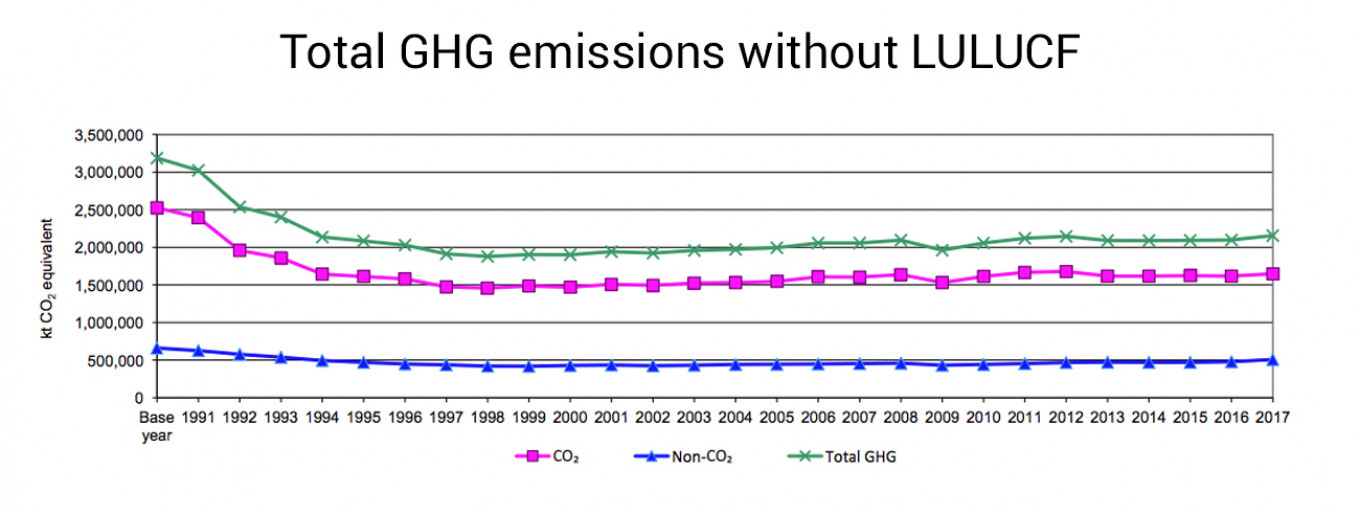

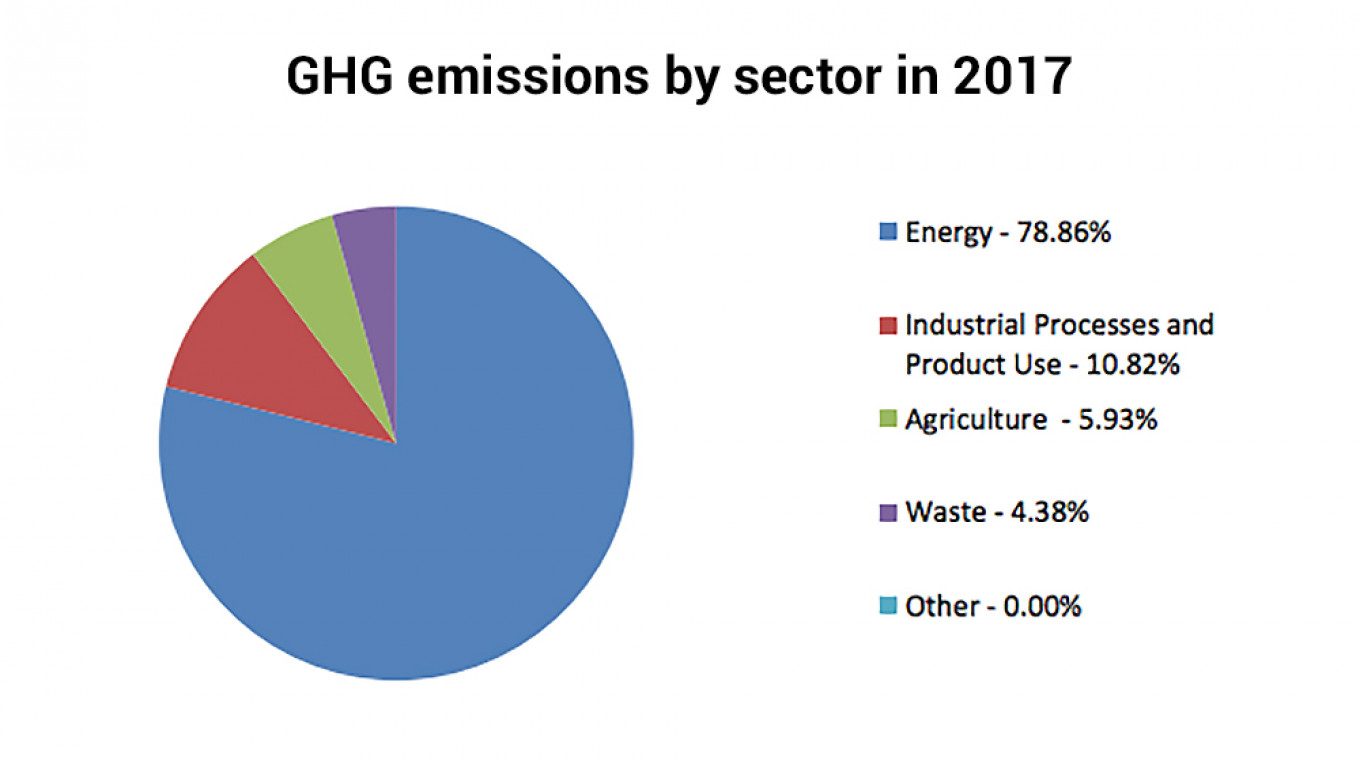

The vast majority of Russia’s greenhouse gases are emitted by the energy industry (78.9%). Nearly half of these emissions come from the production of electricity and heat for the general population, while the rest largely come from the production of solid fuels, petroleum refining and fuels used in transportation.

Russia’s industrial production accounts for a further 10.8% of total greenhouse gas emissions — with metals production accounting for most. Agriculture makes up another 5.9% of total emissions and waste 4.4%.

The findings are consistent with the Russian economy’s continued dependence on fossil fuels, which accounted for around two-thirds of all Russian exports in 2019.

Moreover, Russian companies feature prominently among fossil fuel companies that have emitted the most greenhouse gases in recent decades. According to the U.K.-based Carbon Disclosure Project environmental NGO, Russia’s gas giant Gazprom has been the world’s third-largest emitter since 1988 (after the Chinese coal industry and Saudi Arabia’s Aramco).

Russia’s coal industry, Lukoil, Rosneft, Surgutneftgas, Tatneft and Novatek also all feature in the world’s top 100 biggest emitters.

Compounding Russia’s emission problem is its recent ramping up of coal production, which has increased by more than 30% over the past decade.

Investments in the industry have surged, with several new coal ports under construction, including in the sensitive Arctic region.

While Russia is projected to replace much of its coal use with natural gas in the coming years — leaving a smaller carbon footprint — it is far from sustainable energy use, with projections that only 4% of the energy mix will come from renewable sources by 2035.

The government response

Early this year, Russia’s government released a national action plan that acknowledged climate change as a serious threat to the country’s population and economy and outlined 29 measures for adaptation to be taken by 2022.

The plan cites scientists in admitting that Russia’s average temperature is increasing and that much of the country’s territory is especially vulnerable to adverse weather. It calls on ministries and regional governments to draw up plans for adaptation and to prepare for the increased dangers, including droughts, floods, diseases, and economic costs.

Meanwhile, the plan lists possible economic benefits for Russia from climate change that must be exploited — like increased access along the Northern Sea Route due to melting ice and more space for agriculture and livestock.

However, critics say the plan makes no mention of capping greenhouse gas emissions and is indicative of Russia’s focus on adaptation and capitalizing on climate change.

For example, legislation that would have introduced a quota on companies’ carbon emissions and penalties, as well as a national carbon trading system, was watered down significantly late last year after pressure from a powerful industrial group.

The legislation was stripped down to a five-year audit on companies’ emissions.

Other signs have been more mixed.

President Putin’s much-vaunted National Projects, unveiled after his re-election in 2018 to outline Russia’s long-term development strategy, made no mention of climate change or greenhouse gas reductions. While the ecology part of the strategy does include targets like air pollution reduction, reforestation and waste management, it has faced budget cuts and has only seen about two-thirds of its spending goals fulfilled by the end of last year.

Overall, statements by the government about climate change have been mixed.

The Environment Ministry has for years consistently warned that Russia is being disproportionately affected by climate change, and expressed 95% confidence that human activity had contributed to global warming. It has warned of apocalyptic consequences including epidemics, droughts, mass hunger, water emergencies, forest fires, flash floods and melting permafrost.

Alexander Krutikov, Russia’s deputy minister for the Far East and Arctic, has warned that economic losses related to the melting permafrost are projected to range between 50 billion and 150 billion rubles ($2.3 billion) a year.

Russia’s Audit Chamber, headed by veteran liberal politician Alexei Kudrin, has said climate change could knock 2-3% off Russia’s GDP by 2030.

Those looking to Putin for guidance on the issue will find contradictory statements.

While the president has admitted that climate change presents a danger to Russia’s national security, he has also stopped short of saying that human activity (or fossil fuels) are to blame and has expressed doubts about a shift to renewable energy.

“When these ideas of reducing energy production to zero or relying only on solar or wind power are promoted, I think humanity could once again end up in caves, simply because it won’t consume anything,” he said at a forum late last year.

The Russian president went on to say that those who call for a zero-carbon energy strategy are “trying to lead us all into delusions.” He earlier said that it wasn’t clear why global warming is happening.

Some of his pronouncements have been outlandish. He questioned the need for wind turbines last summer, saying they contribute to bird deaths and force worms to come out of the ground. “This is not a joke,” he said at the time.

However, Putin’s senior advisor on climate change, Ruslan Edelgeriev, earlier this year explicitly said Russia had to reduce its dependence on fossil fuels because they contribute to greenhouse gas emissions.

“They [fossil fuels] contribute to greenhouse gas emissions. They cause both economic and social damage, as well as harm to public health. Some people believe that forest fires are a natural phenomenon. … I believe that we can’t afford to assume that they’re burning as part of a natural process — it’s necessary to intervene and ensure that the forests don’t burn,” he said.

Responses from civil society

Meanwhile, according to polls, environmental problems are seen by Russians as of paramount concern.

According to a January survey by the independent Levada center pollster, environmental degradation was named by Russians as the biggest threat to humanity in the 21st century. Climate change came fourth — after international terrorism and wars.

In the same survey, two out of three Russians said they believe global warming is caused by humans.

Meanwhile, political protests in Russia over the past year have shifted toward environmental problems. These include protests against garbage landfills, air pollution, coal pollution and the destruction of natural habitats.

While the country hasn’t seen massive popular movements dedicated to climate change, a small Fridays for Future movement started last year in Moscow.

So far, it’s only attracted a few dozen, mostly young, activists, who hold small rallies in cities across the country in the hopes of raising awareness of the issue.

Despite being few in number, they’ve already been invited to hold talks with Kremlin officials.

Slowly but surely, Russia is beginning to realize that climate change is not a distant threat, but something that is happening right now.